- Friday, 16 January 2026

Returning To The Roots Through Festivals

When folks in Eastern Nepal start chatting on a bus or in public, one common question is, "Where is your 'pahaad' ghar?" Now, 'pahaad' means hill, but for the people in Eastern Nepal (known as purbelis), it's more than just a hill. In the Tarai region, many people moved from the hilly and Himalayan regions to settle there. Over time, these migrations turned the Tarai, once a forested area, into bustling urban spaces. The whole 'pahaad' connection is rooted in this history of migration that began way back, with significant movements starting around the mid-19th century. New trees grew in Tarai, but their branches kept getting blown away. The first group of people who moved to Tarai wanted a better life through farming because the land was fertile and vast.

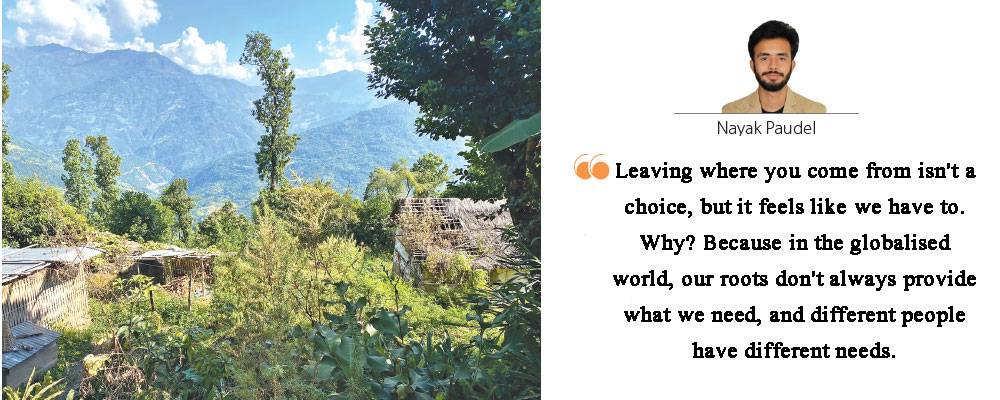

Now, things have changed. The land isn't enough for the new generation. Many people from different parts of Nepal live in Kathmandu because the city offers something more. Leaving where you come from isn't a choice, but it feels like we have to. Why? Because in the globalised world, our roots don't always provide what we need, and different people have different needs.

In the late 1970s, my family's journey began in Tehrathum, where my grandparents, young and full of ambition, cleared trees in Bokre Shanishchare, now part of Pathari-Shanishchare Municipality, to create the very spot my house stands on today. The growing importance of education compelled my father to temporarily live apart while my grandparents established themselves in Morang district. After spending about a decade in Kathmandu, earning degrees and valuable experiences, it has been 15 years since my father returned to his roots and chose to settle there. Until then, our presence in the hills was nonexistent.

During Dashain, our family of four—my father, mother, sister, and myself—made a special journey to our ancestral village, Hwaku, placed in the Aathrai Rural Municipality of Tehrathum. Witnessing the birthplace of my grandfather was a truly unique and emotional experience, bringing our family's roots to life in an intense way. The trip to our roots led to an encounter with Bhanubhakta Sitaula, a historian and writer of Eastern Nepal who lives in our ancestral village. He mentioned that there was no land ownership system during his younger days, which was our grandfather’s time. Yet they nurtured their lands, as agriculture and animal husbandry were their major occupations and sources of livelihood.

As we introduced ourselves to others in the neighbourhood, they expressed happiness at seeing their old neighbours’ descendants return to their roots, even if it was for a short time. I recall what nonagenarian Sitaula said: “We may go away and extend our roots elsewhere, but the place where we once stood will remain there." On the other hand, my concept of our roots (origin) changed when I visited my ancestral village. While there was nothing left of ours on the hill, it was the people who accepted us as the descendants of someone who had lived there before. This acceptance was what allowed us to say that it was our place of origin. Thus, rather than land, I felt that roots are people.

It is because of these people that we return to our roots. Or else, why would we return to a place where there is no one? And being with our people is something we all cherish. This is also exactly why people return to their roots during the festivals of Dashain and Tihar. Annually, before the festivals are at the doorsteps, millions can be seen leaving the Kathmandu Valley and returning to their hometowns to reunite with their families. While it is very possible for an individual living temporarily in a rented room in Kathmandu to not communicate with someone else living as a tenant in the same house, we are familiar with every house in at least a kilometre’s radius, or even more, in our hometown. It is because of the connection we have with the members of our society.

While many people migrated to Tarai during the 19th century, the 21st century has seen a rapid migration from Tarai to the hilly region, as it is where Kathmandu lies. Tarai settlements are vibrant until Chhath, the last festival in a month-long festival period, starting with Dashain and followed by Tihar. Sugam Pokharel’s song ‘Barsa ka dinma lai lai.. Harsa ka dinma lai lai..’ on Dashain and Tihar welcomes the festival period. It assists in recalling the memories of previous Dashain, Tihar, and Chhath celebrations and increases the urge to return to our roots and be with our family members and friends, eat delicious meals, sing, and dance.

Taking tika and blessings from elders during Dashain, putting tika and giving blessings to siblings in Tihar, and worshipping the sun for lighting our lives together with everyone in Chhath make one’s return to his or her roots for almost a month worth everything one deserted.

This year’s Dashain showed how people enjoyed being with their kin and how festivals forced an individual to return to their roots. Many even returned to their karmathalo (place of work) in the two-week gap between Dashain and Tihar, but they had already prepared and planned their fun for Tihar as they would return, for there is nothing like our home, our roots, and our place of origin.

In the age of globalisation, one more member of a family is leaving the place of his or her origin now and then. Humans have continued to enjoy travel and exploration. It is a wave that seems like something unstoppable. But the festivals are what make us return to our roots every once in a while, to realise where we came from and what we have left behind.

(Paudel is a journalist at The Rising Nepal.)