- Sunday, 15 February 2026

Promoting Citywide Inclusive Sanitation

The world is facing a strong challenge to deliver sanitation for all by 2030. According to a joint WHO/UNICEF report, over half of the world’s population, 4.2 billion people, use sanitation services that leave human waste untreated, threatening human and environmental health. The report further suggests that an estimated 673 million people have no toilets at all and practise open defecation, while nearly 698 million school-age children lacked basic sanitation services at their school.

Undoubtedly, the undesired consequences of poor sanitation are devastating to public health and social and economic development. Lack of sanitation systems leads to increasing burden of diahorrea, cholera, vector-born and other neglected tropical diseases, malnutrition and few others. On the other side, significant financial costs can result from sickness and death related to poor sanitation. Moreover, out-of-pocket payments for households seeking health care will significantly rise.

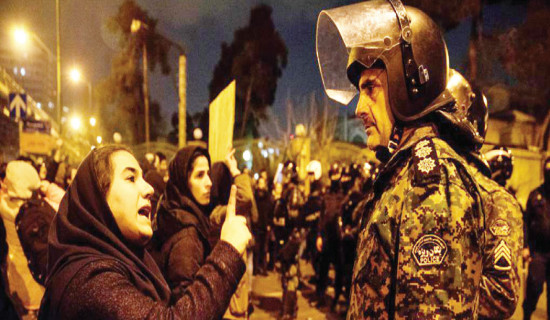

Additionally, poor sanitation has negative social impacts on dignity, poverty, disability, safety, gender and education. In many cities, poorly-managed and shared sanitation facilities may increase exposure to health risks and may lead to reduced dignity, privacy and safety, especially for women, girls and those with limited mobility. Poor sanitation is increasingly considered as a barrier to school attendance and enrolment in many countries. This affects girls in particular, especially after puberty, when their need for menstrual hygiene management may not be addressed.

Women-specific health risks

Moreover, poor sanitation increases women-specific health risks. For example, women who suffer from worm infections and other diseases may become anaemic and undernourished. As a result, this is likely to increase the risk of maternal death. Our cities are also growing rapidly. Migration to urban areas is still on rise. With higher population densities and urban expansion, easy access to water, sanitation and hygiene services for urban poor is still limited. Waste management and urban sanitation in different parts of the cities are becoming even more challenging.

As urban population is still growing, there are profound implications on public health and social development. In the past, the conventional sewerage and waste water treatment were considered as the only solution. Clearly, this will not help us anymore to ensure universal safely managed sanitation. Therefore, Citywide Inclusive Sanitation (CWIS) is a newly emerging approach in urban sanitation systems that largely focuses on service provision and its enabling environment. However, there is limited public awareness, capacity building, coordination with other city services, sharing of good practices, and the use of locally appropriate tools for sustainable urban sanitation services for all.

To put it simply, the CWIS is an innovative concept which aims to meet the sanitation challenges in the urban areas more effectively. Building on the locally appropriate sanitation technologies and practices, the CWIS ensures that everyone has access to and benefits from adequate and sustainable sanitation services in the cities. Additionally, advancing gender equality and social inclusion approach will continue to have profound consequences in terms of leaving no one behind from the basic sanitation services. This approach will greatly help address the inequalities and exclusionary structures and practices within sanitation policies, institutions, decision-making, capacity development, access to information, and accountability.

Unfortunately, vast majority of urban poor live in informal settlements and use on-site sanitation services. Because of the prevailing poor sanitation infrastructures, they have limited access to safe water, sanitation and hygiene services in the communities. During the monsoon, disasters or health emergencies such as COVID-19 pandemic, poor sanitation further worsens their overall health and well-being. While there is a diversity of locally appropriate technical solutions, cities should demonstrate a strong political will and technical leadership to promote the CWIS across the cities. This will ensure that everyone benefits from adequate sanitation services.

More importantly, these services should target specific unserved and underserved groups such as women and children, ethnic minorities, hard-to-reach populations, migrants and people with disabilities in particular. In the context of growing cities, the availability of sanitation in health care facilities, especially in maternity and primary-care settings are still not adequate. Surely, this not only undermines dignity for all people who are seeking health care in the facilities, but also raises questions of quality and equity in health care. Basic water, sanitation and hygiene services in health care facilities are fundamental to providing quality care.

Quality data

Evidence shows that lack of access to sanitation services in health care facilities will have negative impacts on the provision of safe childbirth and access to primary health care. Timely quality data is key to inform more effective policies, targets, budget allocations and pro-poor sanitation strategies. This will not only help in measuring and tracking progress towards ambitious targets of water and sanitation related Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), but also improve accountability, transparency and community participation. Therefore, reliable, consistent and disaggregated data are essential to stimulate political commitment, inform policy-making and decision-making, and enable well-targeted investments to maximise health, environment and economic gains.

In order to further accelerate the progress of the CWIS, it is extremely important to develop a joint technical assistance plan from the partners such as World Bank, Asian Development Bank, UN Habitat, UNICEF, WaterAid and few others and work closely with concerned authorities of the major cities. Key strategic priority actions include multi-sector coordination, capacity building, planning, information system strengthening, and resource mobilisation in order to enhance equity and social accountability in the area of universal access to water, sanitation and hygiene services across the cities.

(PhD in global health, Bhandari writes on health and development issues)