- Sunday, 18 January 2026

Nepal’s New Education Policy: A Scorecard of Pluses, Minuses, and Loopholes

By Dr. Pralhad Karki

Protest in the Streets

In April 2025, thousands of teachers walked out of their classrooms and filled the streets in protest against the proposed School Education Bill. They demanded job security, recognition of past agreements, and control over local appointments. Their movement was powerful enough to shut down schools nationwide, leaving students without classes and parents uncertain of what would come next. Within weeks, the Education Minister resigned. What could have been a milestone in educational reform turned into another episode of political bargaining, where the bill became less about students and more about which party could claim victory or extract concessions.

Ambition Without Anchor

On paper, the new bill looks ambitious. It introduces residential schools to widen access, proposes a Teacher Bank to regulate appointments, promises digital learning programs, and outlines vocational reforms and public–private partnerships. These ideas deserve appreciation. They are not meaningless promises; they respond to genuine gaps in Nepal’s education system. Vocational pathways, teacher management, and digital infrastructure are urgent priorities, and acknowledging them in policy is a step in the right direction.

But ambition without anchor is fragile. A closer reading reveals that these reforms are fragmented, ceremonial, and weakly structured. Without a consistent national vision, even the best ideas risk becoming slogans that will soon be rewritten by the next coalition. Nepal has been through this cycle before. One government declared that all educational trusts must convert into companies, arguing that accountability and taxation would make institutions stronger.

Another government reversed the law, insisting that education must return to non-profit structures, claiming fairness demanded it. Both policies were framed in noble terms, but in practice they served political allies more than students. Institutions scrambled to re-register, not to improve classrooms or learning, but to exploit the loopholes that each new regulation created. Parents faced higher fees, while students saw little improvement in their education.

Favouritism in Practice

Favouritism sits at the heart of these shifts. Teachers’ unions close to ruling parties receive special treatment. Private colleges and schools, often owned by political elites, secure regulatory exemptions. Civil service groups tied to parties fight for recruitment advantages. Policy, instead of becoming a stable 20-year vision, is reduced to a bargaining tool for five-year governments.

The lived experience of students shows how destructive this favouritism can be. Anisha, a talented student from Chitwan, entered a government scholarship interview full of hope. She had excellent grades and a clear vision for her studies. But the panel’s first question was not about her subject or her passion. They asked her which student union she belonged to. She had no affiliation. The scholarship went to someone else. Her story illustrates a painful truth: neutrality is punished, and merit is ignored.

Loopholes Left Open

The new bill also leaves loopholes that will allow history to repeat itself. The idea of public–private partnerships sounds progressive, and the concept deserves credit. With clear rules and accountability, such partnerships could bring innovation and investment to education. Yet the policy does not define how these will be regulated. Without transparency, politically connected institutions will likely capture the benefits while independent innovators are sidelined.

The Teacher Bank, too, is an idea worth appreciating. In principle, it could streamline recruitment and provide stability for teachers who currently suffer from insecure contracts. But the unanswered question is who will control it. If party-affiliated teachers dominate, the Bank becomes a new mechanism of favouritism. Residential schools and scholarships could open doors for disadvantaged students, but without digital monitoring, they risk becoming another avenue for rewarding cadres. Even the fundamental confusion over whether institutions should be run as companies or non-profits remains unresolved, leaving the door open for the next government to swing the pendulum again. These loopholes are not accidental. They are pressure points left open for future manipulation.

The Death of Purpose

The result is a philosophical crisis as much as a technical one. Fairness is replaced by favouritism. Equity is replaced by exclusion. Transparency is replaced by secrecy. Consistency is replaced by chaos. John Dewey once described schools as “laboratories of democracy.” In Nepal, they too often model division instead of a democratic culture. Paulo Freire warned that education must liberate, not indoctrinate. In Nepal, classrooms risk becoming recruitment camps where allegiance matters more than inquiry. Amartya Sen argued that development is freedom, but favouritism narrows freedom to the boundaries of party politics. John Rawls defined justice as fairness, but in Nepal, the race is rigged before it even begins.

When policies are written as pluses for those in power, minuses for those outside, and loopholes for future exploitation, national purpose cannot survive.

Who Pays the Price

The victims of this broken system are always the same. Students lose opportunities when scholarships are captured by politics. Parents pay rising fees without accountability. Teachers are dragged into strikes and punished or rewarded based on their party loyalty rather than their service. Citizens lose trust in the state. And year after year, young Nepalis look abroad for education and jobs, not only because of poverty or lack of resources, but because they cannot see fairness or dignity at home. Brain drain is not simply an economic issue. It is a moral one, born of merit denied.

Toward Real Reform

If Nepal is to move forward, its policies must shift from ceremonial announcements to deeper structural reforms. Professional associations must be depoliticised so that teachers, doctors, engineers, and civil servants represent their professions rather than their factions. Independent commissions for education and civil service must be strengthened, constitutionally guaranteed, and digitally transparent, ensuring that recruitment and promotion are based on merit rather than membership.

A National Education Charter is urgently needed—a 25-year framework that survives governments and provides an anchor of equity, quality, and fairness. Nepal’s aspiration to modernize its education system deserves appreciation. But aspiration without continuity is fragile. To honour these efforts, reforms must be shielded from partisan swings. Every policy must also pass a simple test: does this benefit students? If not, it has no purpose.

A Vision of Rebirth

Imagine a Nepal where teachers focus on teaching rather than campaigning. Imagine private colleges competing on quality rather than political connections. Imagine civil service exams where the brightest rise, not the best-connected. Imagine policies that endure across coalitions and decades, allowing families and institutions to plan with trust. In such a Nepal, education would return to its true role: a sanctuary of fairness, a driver of national purpose, and a reason for students to stay and build.

Today, Nepal’s new education policy risks becoming another scorecard of partisan advantage, more about pluses and minuses than purpose. It is full of loopholes that allow parties to manipulate it in the future, just as they have in the past. But this does not have to be the ending.

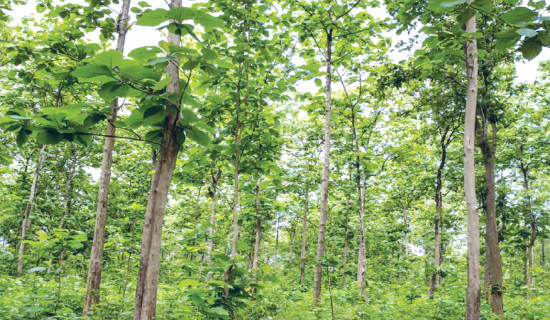

If we can close the loopholes, depoliticise associations, anchor policy in continuity, and put students first, education can still become the banyan tree it was meant to be—roots deep in Nepali soil, branches open to the world, and shade wide enough for every child.

The rebirth of Nepal will not begin in parliaments or palaces. It will begin in classrooms.