- Friday, 13 March 2026

A Treatise On Systematic Change In Nepal

Dr. Lok Raj Baral, an MA in Political Science from Tribhuvan University (TU), distinguished Professor, prolific writer having worked on 25 books, both authored and edited, frequent contributor to national and international newspapers and journals, and short-term Ambassador of Nepal to India, has published a new book on a subject of contemporary interest.

He was Head of the Political Science Department of TU. He also had a stint in the Centre for Nepal and Asian Studies, TU. Baral was the founding president of the Nepal Centre for Contemporary Studies. He also guided PhD pursuits of many scholars.

In his public life, he served as President of the Nepal Council of World Affairs. He was also president of the Political Science Association of Nepal that split into two separate entities on political grounds. In terms of academic contributions, Baral was a visiting professor at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, US, and a visiting fellow at Chr Michelsens Institute, Bergen, Norway.

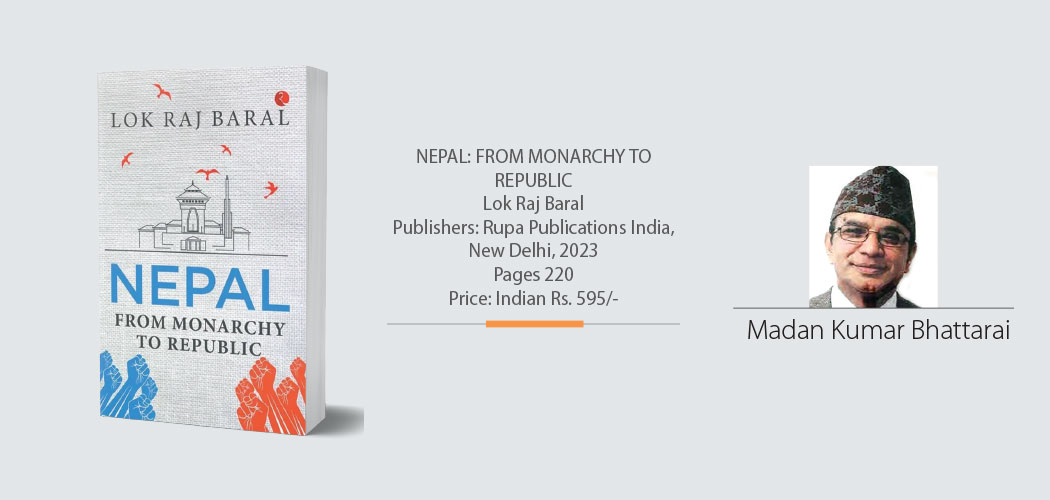

The book dedicated to the memory of his spouse, Ganga Baral, who died prematurely, is entitled NEPAL: FROM MONARCHY TO REPUBLIC. It is an important addition to the literature on the politics of Nepal at a time when Nepal is on a political trajectory of republican order after 240 years of monarchical rule.

Apart from division into eight major chapters, including a 4-page long conclusion, the book contains a long introduction setting the agenda with 24 pages and a 4-page long epilogue. Before dwelling on the contents, it may first be advisable to go into the preface, setting the tone for the context of quite admirable work that the author has successfully attempted, as he is so active even when he is already on the wrong side of the eighties.

Professor Baral came into the limelight in 1977 after the publication of his first book, rated as a "classic", based on his doctoral thesis presented to the School of International Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, pertaining to oppositional politics in Nepal. He also enunciates six main characteristics of Nepal's politics and foreign policy, three of which directly or indirectly pertain to various aspects of monarchy.

The author paints a mixed note on the future course of Nepali politics. On the one hand, he finds Nepali politics "on the right track", propelled by regular elections and the operation of constitutional processes, though "fraught with uncertainties and popular despondency"; he reads the track record of republican dispensation as being far from "promising" with considerable deficits on the delivery front, on the other.

The first chapter, The Native Construction of a Nation State, is a sweeping summary of Nepal's political developments during the Shah and Rana periods, ethnic demands for identity and relations between monarchy and army. The second chapter, The Rise and Fall of Monarchy, intends to succinctly encapsulate the period from the unification of the country by King Prithvi Narayan Shah to the ascent of republican order, including the role of the Nepal Army and the influence of external powers, most notably India after its independence.

Quite understandably, the third chapter, Parties and Problems, is the longest, as it dissects the evolution, role and trends of political parties both during the monarchy and the post-republican era. Chapter four, pertaining to the institutional crisis of governance, is possibly the most pertinent in Nepal's contemporary scenario.

Problems of Democratisation is the title of the fifth chapter that speaks of fractured political culture in Nepal in greater detail and a looming crisis in diverse sectors of our economy. The sixth chapter, Economics of Governance, is possibly the most important and probably the least prioritised sector in our context.

The seventh chapter, Geopolitical Dimensions and Change, may be taken as the foreign policy proper of the book. It seeks to study Nepal's foreign policy from different aspects of what can be called SWOT analysis in the field of management. This chapter deals, among others, with the new map of Nepal, including Lipulekh, Kalapani and Limpiadhura, and Baral charges Nepal's political parties for what he calls "politicising the issue" with the resultant impact that the "scope for a negotiated settlement is now more complicated".

Though he served in New Delhi as Nepal's ambassador for a period of about 14 months, as acts of shuffling ambassadors and recalling them are not new in Nepal, especially after the political change of 1990, his reading of the status and role of the embassy he served may be noted with some interest.

Referring to growing trends to give preferences to pursuing personal contacts rather than developing institutional linkages in diplomacy, he laments that our embassy in Delhi has "been perennially bypassed by both the Nepali governments and the Indian side as if it exists only to complete formality".

Possibly drawing from his own bitter experience as ambassador, Baral echoes similar experiences of top diplomats who have served in the largest of our missions in the capital of our southern neighbour. He says, "And Nepali political leaders try to avoid the representation of the Nepal Embassy in higher-level talks held between the government leaders of India and political leaders of Nepal."

Baral's premature recall as Ambassador to India was the result of the fall of the Nepali Congress government led by Sher Bahadur Deuba following bitter conflict in the party called Antarghat, a popular political lexicon in Nepal meaning insidious activity.

The Times of India, in its May 11, 1997 edition under "Capital Notebook", talked about this action by the Nepalese government under "Short Shrift", drawing parallels between the episode of his recall from India and the resignation of his close academic friend, Professor Bhabani Sen Gupta (with the literary name of Chanakya Sen), who was forced to resign on May 6, 1997, within twenty-four hours of his appointment as foreign policy adviser to Prime Minister Inder Kumar Gujral.

Baral's portrayal of the Nepali political scene, the role of political actors and the prognosis of Nepal-India relations may be subject to differing interpretations and even sharp retorts depending on the attitudes and orientations of readers. But there is absolutely no doubt that he has contributed a lot in bridging the yawning gap that exists between what is called forward stride march of Nepali politics and the availability of publications on the subject.

I congratulate Baral on his admirable endeavours and wish he wrote a new book dealing with his stint as ambassador to India.

(Dr. Bhattarai is a former foreign secretary, ambassador and author. kutniti@gmail.com)

-(2)-original-thumb.jpg)