- Thursday, 31 July 2025

Women-friendly Transport

The Nepal Transport Service introduced a public transportation system in 2016 B.S. Although it was technically accessible to women from the start, societal conservatism, family restrictions, and safety concerns discouraged their use. The lack of reserved seats for women made matters worse. So, it was dominated by men. Even 66 years later, the situation remains largely unchanged. Still, women face difficulties while commuting by public buses.

One and a half decades into the introduction, women's education gradually increased, and so did the job opportunities, such as teaching and nursing, making buses essential for their daily commute. Swastika Sharma, a student in Kathmandu in 2035 B.S, sharing her first experience of a bus ride, said, “My hands trembled the first time I boarded a bus alone. The stares, the whispers made me feel like I was doing something wrong. But I told myself, if I want to study, I have to be brave.”

Her emotions captured the fear of public judgment, the risk of harassment, but also the quiet courage to break barriers felt by women during the 2030s. Although social norms still discouraged women’s independence and incidents of harassment persisted, public transport slowly became more accessible and socially accepted for women during that decade, marking an important shift towards greater female mobility. Slowly, the concept of reserved seats for women was introduced along with an increasing number of routes inside and outside the valley.

This improved women's safety and encouraged women’s mobility. More women began using public vehicles due to rising female literacy, urban migration, and job opportunities. Over the years, in response to complaints that women were facing groping and sexual harassment while travelling in crowded buses, NGOs and women’s rights groups ran awareness campaigns about harassment on public transport. Tulsi Prasad Sitaula, a senior official at the Ministry of Physical Infrastructure and Transport, even pointed out the need for women-only public vehicles. But no such vehicles have been in operation to date.

In 2070 B.S., women-only microbuses were started in Kathmandu and other major cities as pilot projects to address the complaints of verbal abuse, physical harassment, and inappropriate touching on crowded buses, which were commonly reported by students and working women. However, the number of such uses was limited. Slowly, women-only microbuses largely disappeared from public consciousness, seen only occasionally and only on select routes. However, there is no clear evidence that they have been fully discontinued.

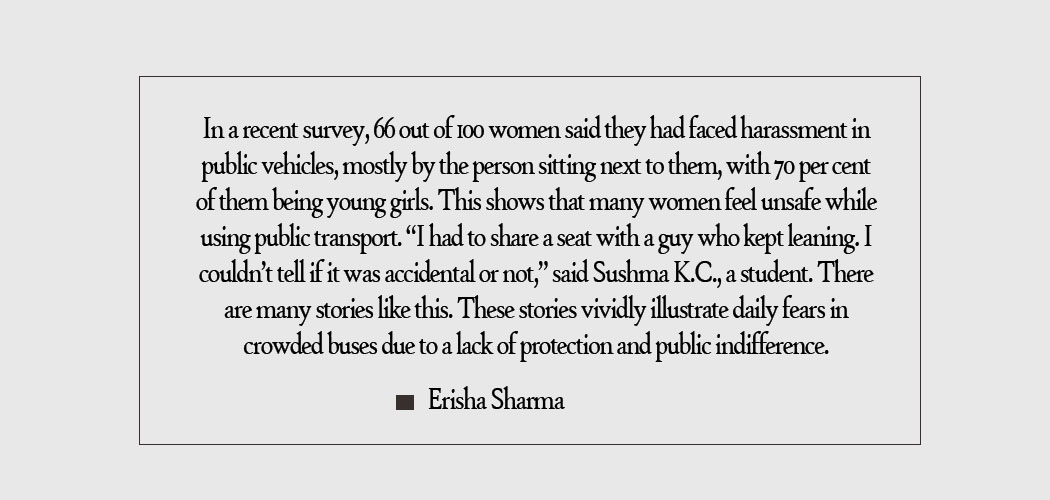

In a recent survey, 66 out of 100 women said they had faced harassment in public vehicles, mostly by the person sitting next to them, with 70 per cent of them being young girls. This shows that many women feel unsafe while using public transport. “I had to share a seat with a guy who kept leaning. I couldn’t tell if it was accidental or not,” said Sushma K.C., a student. There are many stories like this. These stories vividly illustrate daily fears in crowded buses due to a lack of protection and public indifference.

The Metropolitan Police data shows hundreds of harassment complaints yearly in the Kathmandu Valley. There might be many incidents going unreported due to victims’ fears of stigma and low confidence in the justice system. On the other hand, to address these issues, various NGOs are pushing hard for CCTV cameras, dedicated helplines, staff training, and legal reforms. It’s not perfect yet, but public transport in Nepal is improving bit by bit.

-original-thumb.jpg)

-square-thumb.jpg)