- Sunday, 15 February 2026

Chaku: Tokha's Sweet Tradition

As you arrive in Tokha during the winter months, a warm and inviting aroma greets you, the distinctive scent of Chaku being prepared. Local Chaku businessmen work tirelessly, spending extra hours to prepare and distribute this traditional delicacy to markets, which is popular on the occasion of Maghe Sankranti (the first day of the 10th month in the Nepali calendar), which falls on January 14 this year. The streets are filled with stalls offering this Newari delicacy alongside sesame confections, popularly known as 'til ko laddu.' For generations, Chaku has been a hallmark of Tokha’s culturer

Sugarcane farming

Tokha, historically known as ‘Tun Khya’ in Newari, derives its name from ‘Tun’ (sugarcane) and ‘Khya’ (farm). In the past, Tokha was a hub for sugarcane farming. Over time, the name evolved into Tokha, but its legacy for sugarcane farming remains carved in its identity. According to Buddha Shrestha, 42, proprietor of Kashilal Chaku Production, Chaku originated as a creative solution to excess sugarcane during his great-great-grandfather’s time. He said, “In the past, people could not finish ripened sugarcane on their own. So, they started to think of ways to consume it and created Chaku.”

Shrestha is the fourth generation in his family to continue this tradition. He and his two brothers learnt the skill from their father during childhood and have been carrying it forward ever since.

He said during the time of his great-grandfather, people used to manage every aspect of production, from raw materials to packaging. Chaku was handmade, with no machinery involved. Organic materials such as straw and corn leaves were used for packaging. However, urbanisation has transformed Tokha, leading to a decline in sugarcane farming at present, he added. Now, producers rely on purchased molasses, but they continue to uphold traditional methods of making Chaku, adapting only minimally to modern tools. Rabindra Shrestha, a Chaku businessman, also shared a similar story. He learnt the skill from his father. At present, he, along with his five family members, is busy preparing Chaku. He said that Tokha produces Chaku primarily for two months in a year. As it is a prime season, we leave everything behind and make Chaku.

Chaku making

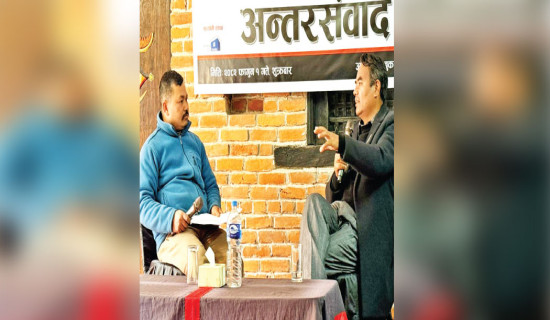

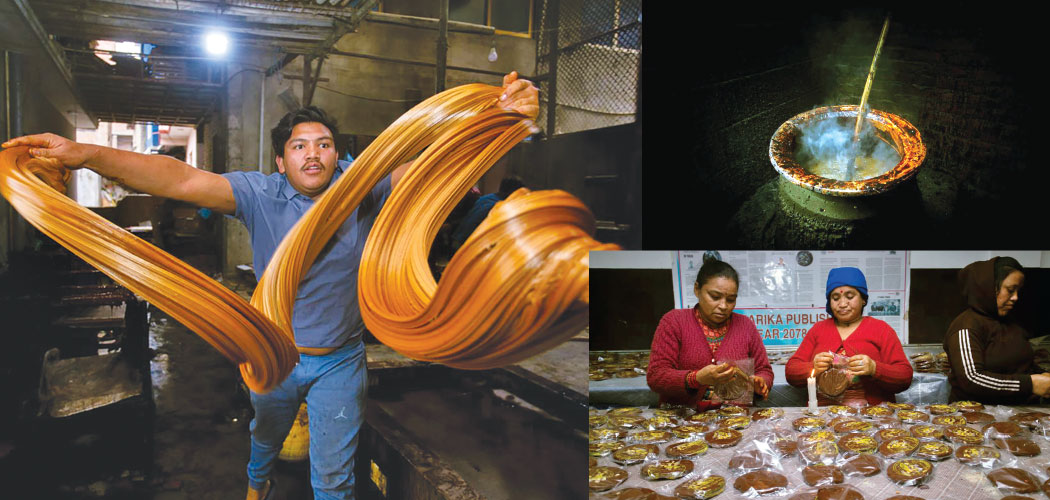

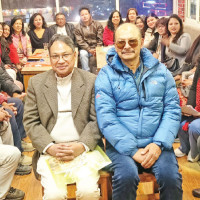

Chaku production is a meticulous process. Molasses is boiled at high heat for about an hour before being poured onto a greased or silicone surface to cool slightly. The molten mass is then repeatedly stretched and folded for 10-15 minutes, incorporating air to achieve its shiny, silky texture. Once ready, the pliable Chaku is shaped as desired before it hardens. Despite the physical demands, producers like Buddha and his family remain committed to this labour-intensive technique.

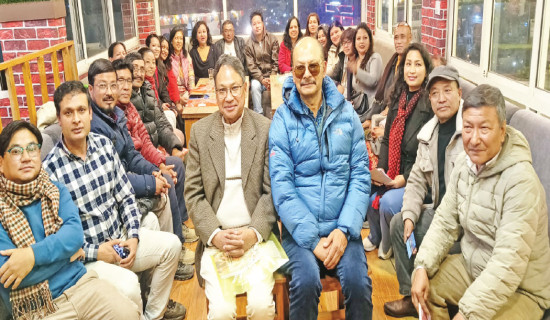

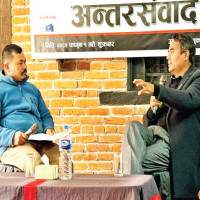

Buddha has been making Chaku since his childhood. When we enter his enterprises, the production is on full display. We can see two large pots placed above firewood, containing boiling molasses. Next to it, boiled molasses is poured on the box-shaped floor to cool it down. Additionally, we can see people busy pulling and stretching that slightly cooled molasses, some busy shaping them and some busy packaging them.

While Buddha’s two younger brothers produce Chaku only during the peak season, he works year-round. He said these two months are like a golden period, where we work very hard and enjoy the returns throughout the year. He said that he uses around 1,000 sacks of molasses weighing 50 kilograms each during the peak season every year to produce Chaku, which is 90 percent of his annual Chaku production. Besides this, Buddha is also involved in farming during the remaining ten months. Additionally, he assists his brother’s sweet shop during occasions like Tihar, Mother’s Day, and Father’s Day, when the shop experiences a massive flow of customers.

Chaku is also consumed during Yomari Punhi, approximately a month before Maghe Sankranti, making this a 1.5- to 2-month-long business for many producers.

Tokha is home to 14 Chaku enterprises, mostly operated by Newar families in Wards 1, 2, and 3. Together, they produce 70 per cent of the Chaku consumed during Maghe Sankranti, with the rest sourced from Bhaktapur, Khokana, and Lalitpur. In total, Tokha produces approximately 400,000 kilograms of Chaku for the festival. These products are distributed to major markets like Asan, Indrachowk, Bhaktapur, Kirtipur, and Patan.

Chaku is more than a treat; it is a cultural and health asset. It is a staple during the cold months as it helps generate body heat. Additionally, it is especially beneficial for breastfeeding women, aiding in milk production. Buddha said that earlier, only Newar communities used to consume Chaku, but knowing its health benefits, he now gets orders from all other communities.

Business challenges

Despite its rich history, Chaku production faces challenges. Urbanisation has reduced sugarcane farming, forcing producers to rely on imported molasses. Moreover, youths have lost interest in this seasonal business. Many enterprises do not tend to purchase machinery for the business as it only blooms for two months. Thus, the Chaku-making process is completely manual and a tiring job.

They say they could not afford operating and maintenance costs for machines just by doing business for two months. Moreover, youths now are associated with firms or companies, which makes it difficult for them to take such a long holiday to continue their hereditary business.

Meanwhile, young enthusiasts, like Royal Shrestha, 18, see hope in this Chaku business. Royal, who has learnt to make Chaku since he was four, pointed out the need to promote Chaku globally. “Currently, Chaku is made traditionally, completely by hand, due to limited demand. But if we create derivative products like candies and desserts and promote them, we could establish year-round demand and grow it into a thriving industry,” he said.

Photos by Manoj Ratna Shahi

(Maharjan is a journalist at The Rising Nepal.)

-square-thumb.jpg)