- Friday, 27 December 2024

Trump Wins, In Spite Of Media

Far from being done, Donald Trump has bounced back for the key to the White House four years after he left the executive office of the world’s most powerful nation. He is the second candidate to win a non-consecutive second term, the last time such an event having occurred in 1892. Trump defeated America’s only two women candidates—both from Democratic Party—for White House terms. In 2020, he outpolled Hillary Clinton, the wife of former President Hillary Clinton, and this time he edged past Kamala Harris.

In 2024, he survived two assassination attempts and massive media onslaught questioning his credentials, competence and personal integrity. Surveys indicate that voters, who traditionally supported the Democratic Party, gave their verdict in Trump’s favour this time. They wanted someone to act quick and not to deviate from the declared policy. Democrats are devastated by Trump’s comfortable margin of victory and Republicans’ retaking control of the senate that impeached him. Republicans hope to hold majority in the House of Representatives as well. If they do, Trump’s administration’s task in introducing new policies will be easier.

Several foreign leaders, including those in the UK, France and Ukraine spoke harshly against Trump during the latter’s poll campaign. They are examples of how loose tongues can inflict lasting embarrassment. The1990s were the best decade for the US and its allies, when the unipolar world was free of the Cold War. The Soviet Union disintegrated and Russian military weakened in a basically demoralised nation dealing with galloping inflation.

The old won’t do

Deviation from Western course should not inevitably invite sanctions. No sovereign nation likes to be under the thumb of any other nation—big or small, rich or poor, militarily strong or weak. But some powers want to extort obligations and enforce their writ on others. Economic sanctions are a deformity often in the guise of sovereign, democratic exercise for national security and vital interests of the militarily powerful. Confident, decisive and no-nonsense leader, Trump represents many manifestations. The only president to have snubbed the mighty news media without batting an eye lid—not for a year or two but through his first four years in office and then another four in the 2024 poll campaign trail. He speaks bluntly to the media as thriving on fake news, as he does not believe in treating them with kid gloves.

Europe will have to reassess its dependence on the US. Soon after he entered the White House for a first in office (2017-21), Trump told NATO members to chip in their due for the organisation’s defence expenses instead of expecting the US to meet the deficit as a matter of routine. A growing number of nations conclude that Israeli action in Gaza has crossed too many red lines so visibly that its close allies, too, find it hard to defend it credibly. Trump cannot dismiss the significance of many Muslim voters who put their bets on him in the hope that he will work out a ceasefire in Gaza, where nearly 48,000 Palestinian civilians, mostly women and children have been killed since October 2023. Celebrating his victory on Wednesday, Trump pledged to end, not start, wars. Well, he could begin with Gaza.

During the year-long campaign, Trump claimed that, if elected, he would bring about a closure to the Ukraine war “in one day”. He has his chance to deliver by over-riding the strong Jewish lobby and getting tough with Tel Aviv. Such action will boost his public ratings early on—perhaps by the time he completes his first 100 days in office. Many expect him to pursue a policy of mass deportations of illegal immigrants. He just might. The new world order does not mean the US is a spent force. Its role will continue to be significant, especially in a multipolar world landscape. If India, Russia, China and regional groupings in Africa, West Asia and East Asia hope to air better voices, why will not the US? The only change is that American hegemony across the globe will drastically reduce.

US's China contain policy has imposed 100 per cent tariff on the country’s electric vehicles. However, 25 per cent of the cars plying on European roads are made in China. In retaliation, Beijing has clamped restrictions on US farm produce, which has already begun hurting American farmers. Canada, too, has been affected by similar measures. Australia tried to ape American policy but took a U-turn within a year. For the world supply chain is intertwined. The rest of the world sees an opportunity to be assertive for airing dissenting views. Having shed the financial discipline entailed by the gold standard, the US engaged in roller-coaster spending spree and consumerism for more than half a century, especially since the 1970s to the extent of fuelling its national debt from $400 billion in 1971 to $35 trillion today.

Big challenges

Payback time has begun amidst loud signs of concerns. The stupendous task of servicing the national debt creates a grave alarm in the American intelligentsia and business community. Elon Musk, the high-profile CEO of the automotive company Tesla and heavy investor in space technology, has warned: “At current rates of government spending, America is in the fast lane to bankruptcy.” Defence spending is high, what with some 800 American military bases stationed in about 80 countries. This might be largely squared off by the revenue generated from weapons exports in a country where the top ten per cent of the population own more than two-thirds of the wealth as against the bottom half accounting for only three per cent.

What went wrong with the analysts wooed by the major media? Only 30 per cent of American youth in the age group of 18-29 trust the news media highly. On average, not more than 45 per cent of Americans trust the news outlets. Yet much of the international community relies on the media distrusted by Americans for information on Trump and global issues. At a time when America’s overwhelming hegemony is on the verge of slipping sharply, a confident-sounding Trump has his chance of steering the country to a pragmatic course in deference to the multipolar world that is clearly in sight.

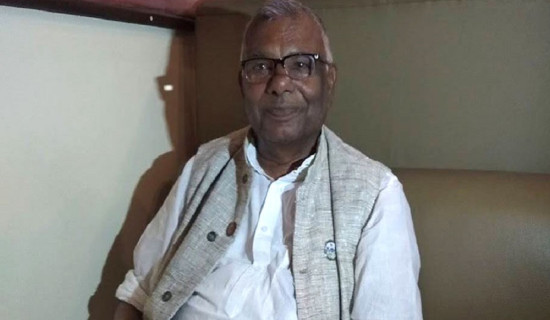

(Professor Kharel specialises in political communication.)

-original-thumb.jpg)