- Wednesday, 17 December 2025

Transitional Justice Process In Nepal: The Way Forward

The recent amendment to the Enforced Disappearances Inquiry, Truth and Reconciliation Commission Act, 2014 offers a unique opportunity to successfully conclude the long-overdue transitional justice process in Nepal. Following the authentication of the amendment by President Ramchandra Paudel after the formation of the Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli-led government, three major political parties agreed to reconstitute the recommendation committee formed to nominate the candidates of the office-bearers of the transitional justice commission. This demonstrates that political leadership, despite their divergent ideological stances, is still on the same page about resolving this issue. There is still uncertainty, however, as the tripartite agreement on the formation of such commissions continues the trend of excluding victims and relevant stakeholders from such processes and fails to engage them in the transitional justice process. This article briefly discusses the potential obstacles to ensuring the smooth implementation of Nepal’s transitional justice process.

Nepal's journey to transitional justice began with the signing of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) in 2006. CPA stipulates that a high-level Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) be formed to probe into “those involved in serious human rights and crime against humanity in the course of the armed conflict for creating an atmosphere for reconciliation in the society." The CPA also promised to “guarantee the right to relief of the families of the victims of conflict, torture, and disappearance."

This alludes to a deliberate inclusion of ambiguous wording, leaving a broader scope for interpretation. The CPA also fails to specify the mandate of the commission and how the commissioners will be chosen. It is also unclear whether individuals who violate human rights and commit crimes against humanity will face criminal prosecution. This gives space to the conflicting parties to interpret the mandate of the commission to establish truth and provide reparation to the victim while also providing enough space for human rights advocates to appear in the criminal prosecution. This ambiguity in the CPA resulted in a debate popularly called 'peace versus justice' which substantially delayed the process. Political actors from the beginning have been reluctant to establish any accountability mechanisms; rather, they have adopted a policy to provide administrative reparation to the victim.

Nevertheless, after the arrest of Colonel Kumar Lama of the Nepali Army in 2013 by the British Police under the Universal Jurisdiction provided to it through the UN Convention against Torture, a third country may prosecute individuals for serious crimes against international law such as crimes against humanity, war crimes, genocide, and torture if a country of the origin of the crime is unwilling or incapacitated to prosecute those responsible.

Nepali politicians feared that if they did not adopt the transitional justice process, they could be subjected to international prosecution as well. As a result, an Ordinance on the Enforced Disappearances Inquiry, Truth, and Reconciliation Commission was promulgated by the then government in 2014. Since the Ordinance was designed in line with the South African model of transitional justice, incorporating an amnesty scheme even for heinous crimes, the Supreme Court of Nepal struck it down in 2014. Following the order of the Supreme Court, the Legislative Parliament in 2015 passed a law with minor improvements in the provisions of the Ordinance and not going beyond the South African approach to transitional justice, which was considered a controversial process in the past couple of decades. However, the Supreme Court invalidated that Act again on the same ground.

Since the Truth Commission and the Commission of Enforced Disappearance were already in place before the court ruling, they remained unchanged. Stakeholders, including victims, demanded the dissolution of both commissions and chose not to cooperate, as the law was not amended in accordance with the court order and the victims, human rights community, and other stakeholders were not consulted in the formation of the commission. Moreover, the UN also circulated a technical note to development partners encouraging them not to cooperate with the flawed transitional justice process.

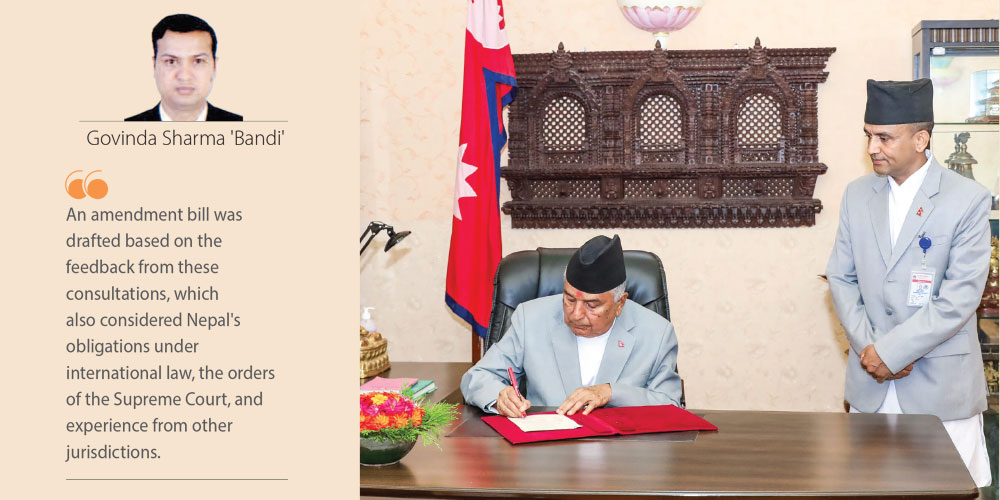

Consequently, both commissions became completely dysfunctional, and Nepal's transitional justice process was stalled for a time. In April 2022, the Law Ministry took the lead to reinitiate it by conducting a series of consultation meetings with victims and other stakeholders across the country. An amendment bill was drafted based on the feedback from these consultations, which also considered Nepal's obligations under international law, the orders of the Supreme Court, and experience from other jurisdictions. But the political consensus could not be reached on the new bill. Additionally, the tenure of the officials was expiring. Despite huge political pressure on the law ministry to extend the tenure of the committee, the ministry decided not to extend the terms of the office of the officials of both commissions, which significantly lacked trust and credibility.

Instead, the Law Ministry also took a risk to proceed with a bill to which the parties in the government agreed but which was not fully compatible with Nepal's obligation under international law and the Supreme Court ruling considering that this attempt would, at least, make this amendment bill a property of the parliament, inviting a public debate. Because of this process, Nepal has an amended law that is promulgated in line with Nepal's obligations under international law and the Supreme Court ruling. If the Law Ministry had not taken the risk of dissolving the defunct commissions, enjoying no trust of the victims and stakeholders, and registering a bill even with incumbent flaws, there would have been minimal chance of having this law with all the improvements.

However, this is only a beginning, and there is a long way to go. Transitional justice is about ‘transformative justice’ where reparation of the victim is at the centre rather than 'retributive justice’ where the accused and standard of proof are at the centre. Nevertheless, criminal accountability for serious crimes also became a major part of the 2022 scheme.

The comparative practice suggests the success of transitional justice lies in the credibility of the process. For example, the transitional justice laws and practices in South Africa and Columbia do not fully comply with international law, but they are relatively considered successful cases. In both cases, the process was designed with a bottom-up approach, and the victims have been at the centre of the process. However, in Nepal’s context, it seems to be the opposite, wherein political decisions are made at the top and concerned stakeholders come to know about them from the media. The recent three-party decision at Baluwatar on the reconstruction of the recommendation committee is the latest example of a top-down and non-inclusive approach, which, if continued in the future, would definitely endanger the recently reinstated process.

Therefore, participation of the victims and other stakeholders in the process is of utmost importance to its success. In the past, we made many mistakes, but the hope is now not to repeat these mistakes again. Instead of three-party negotiation for the new office bearers, an open and transparent formation process will ensure the commission's independence, thereby achieving lasting peace in a divided society.

(Bandi is a former minister for Law, Justice and Parliamentary Affairs.)