- Wednesday, 4 February 2026

Protection Of Nepal's Intangible Heritage

Nepal ratified the 2003 Convention on Safeguarding Intangible Cultural Heritage in June 2010 (ICH Convention), becoming the 125th country to do so. Article 16 of the ICH Convention provisions for the Representative List of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity (Representative List) to ‘ensure better visibility of the intangible cultural heritage.’ Even after 14 years of ratifying the Convention, Nepal has fallen short in getting its intangible cultural heritage listed.

The list is yet a faraway dream for Nepal. Prior to even sending a nomination file for the listing, Nepal is yet to meet its obligations enlisted in the Convention. For instance, Nepal was to submit its periodic report in 2016, which it could not. The next deadline to submit the report is 15 December 2024.

With 14 years already passed since Nepal ratified the Convention, it will have to report regarding the safeguarding measures it took over these years. The ICH Convention in Article 11 mandates each state party to take necessary measures to safeguard the intangible cultural heritage present within its territory and to do so by identifying that heritage with the participation of communities, groups, and relevant non-governmental organizations. To ensure the identification, each state party needs to draw up one or more inventories of intangible cultural heritage present within its territory, Article 12 of the Convention states. It further mentions that the periodic report shall have information regarding those inventories.

The Convention is flexible towards state parties when it comes to drawing up the inventories. It clearly states that state parties are free to form the inventories ‘in a manner geared to its own situation'—meaning they can choose the number, the design, the format, the approach, the criteria, and even the way they want the communities to be involved, as they deem appropriate according to their circumstances. This leeway provided by the Convention is beneficial for countries like Nepal.

Since there is no single binding model or template that Nepal has to abide by, it can accommodate the documentation of various and distinct intangible cultural heritage, according to the nature of the heritage. Furthermore, the Convention also provides room for one or more inventories, which means that with the introduction of federalism in the country, this can be delegated to provincial and local levels as well, and each local level can have its own inventory that can be added up to one national inventory list. Additionally, the Operational Directives for the Implementation of the Convention outline eight guiding principles, such as having consent and involvement of the concerned community, inclusivity, and accessibility of the inventory list.

Between 2012 and 2013, the Ministry and UNESCO Office in Kathmandu organised three workshops, first on the implementation of the ICH Convention, second on the community-based identification and inventorying of the

intangible cultural heritage, and third on the preparation of nomination files for the Representative List.

Similarly, it carried out a three-month (from June to August 2013) practical field survey and inventory of three communities in Nepal. These efforts that had taken some flight in 2013 seemed to slow down in the following years. The post-earthquake heritage safeguarding efforts were majorly focused on the restoration and rebuilding of the tangible cultural heritage.

In terms of laws and policies directed at safeguarding intangible cultural heritage, the Ancient Monuments Preservation Act 1956 (AMPA) takes a rather narrow approach to heritage preservation, limiting itself to the preservation of ‘ancient monuments’ and ‘archaeological objects.' With not even a mention of the term ‘intangible’ in the whole text of the AMPA, it has become evident that the current legislation falls short in safeguarding intangible cultural heritage.

The National Cultural Policy 2010 recognised intangible heritage as an integral part of Nepali cultures and referred to its identification, evidence-based research, protection, and management as its purpose. The policy stated the need for acts, regulations, and directives for the implementation of the policy itself, which are yet to be drafted.

At present, the responsibility to draw an inventory of intangible cultural heritage in Nepal resides on the Department of Archaeology (DoA), which works under the Ministry of Culture, Tourism, and Civil Aviation. There have been some efforts in inventorying tangible cultural heritage of certain places within the country by the DoA, but no such efforts for intangible cultural heritage have been put out on its website.

In this regard, the Lalitpur Municipality had prepared a report titled ‘Intangible Heritage of Lalitpur: Festivals and Carnivals’ in 2020. The report consisted of the list of festivals and carnivals along with their details and images. The report can be a good starting point as guidance for creating a national inventory list. To do so, there needs to be a consent form signed by the concerned communities, which is mandatory under the ICH Convention.

There can be a separate website to have the lists made public, similar to practices followed by various other countries such as India and France. Alternatively, as suggested earlier, each local level can have its own inventory list, made public on its website.

However, these lists need to be updated in a timely manner, and the elements can be added as they get documented. Inventorying need not be a one-time project and should be made part of budgeting in each term.

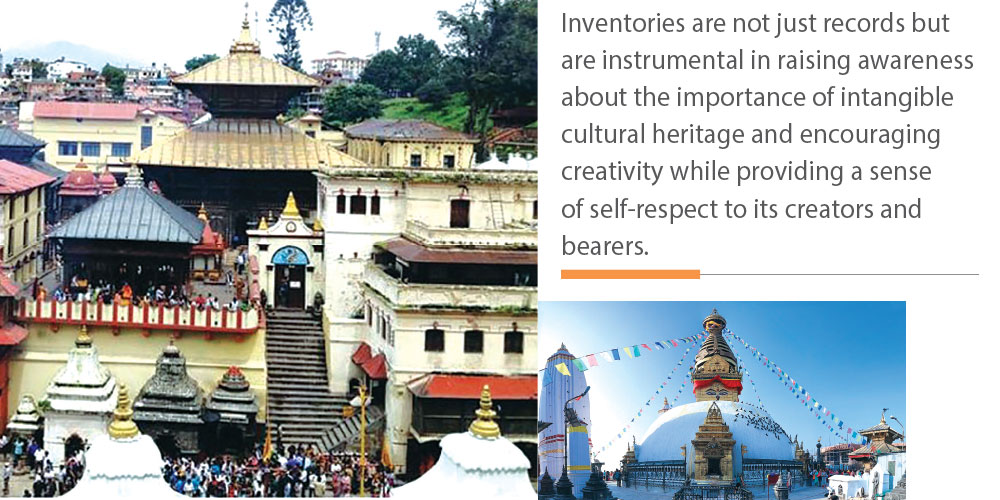

Nepal as a country should take the task of inventorying its intangible cultural heritage not merely as an obligation to fulfil under the ICH Convention. Inventories are not just records but are instrumental in raising awareness about the importance of intangible cultural heritage and encouraging creativity while providing a sense of self-respect to its creators and bearers. They are paramount in transmitting knowledge regarding intangible cultural heritage to future generations. Otherwise, the future generation will grow up with a rather narrow outlook towards heritage conservation, believing that only tangible cultural elements such as temples, monuments, and images are to be preserved. So, it is high time that Nepal scales up its efforts in inventorying its intangible cultural heritage.

(Dangol is actively involved in cultural heritage preservation projects in Nepal and London.)