- Tuesday, 10 March 2026

Moving Beyond The Mind

Acharya Rajneesh, commonly known as Osho, is among the few philosophers who have given a new dimension to meditation and consciousness. He transformed the perception of meditation, demonstrating that it could be enjoyable and entertaining, contrary to traditional ideas and techniques, which often require a special setting and the sacrifice of family life and worldly pleasures. He developed numerous dynamic meditation techniques that included physical activities such as shaking and dancing. These techniques were designed to release existing stress and tension before moving into silent meditation.

As a staunch critic of institutionalised religion, Osho created a robust synthesis of Eastern and Western philosophies. He drew anecdotes from various religions, including Hinduism, Buddhism, Islam, Jainism, Taoism, and Confucianism, though Buddha and Krishna seem to have been his favourites. It is rare to find a philosopher who respected all religions and spiritual philosophies as much as Osho did. This convergence of ideas and spiritual traditions from the East and the West has resonated with people from diverse religious beliefs and cultural practices across the world.

Exploration of love, relationships, and sexuality—issues central to modern life and discourse—were among Osho's favourite topics. He advocated for a more open and conscious approach to these areas for spiritual attainment, emphasising freedom and honesty. He consistently championed individual freedom, asserting that without it, true spirituality could not be pursued.

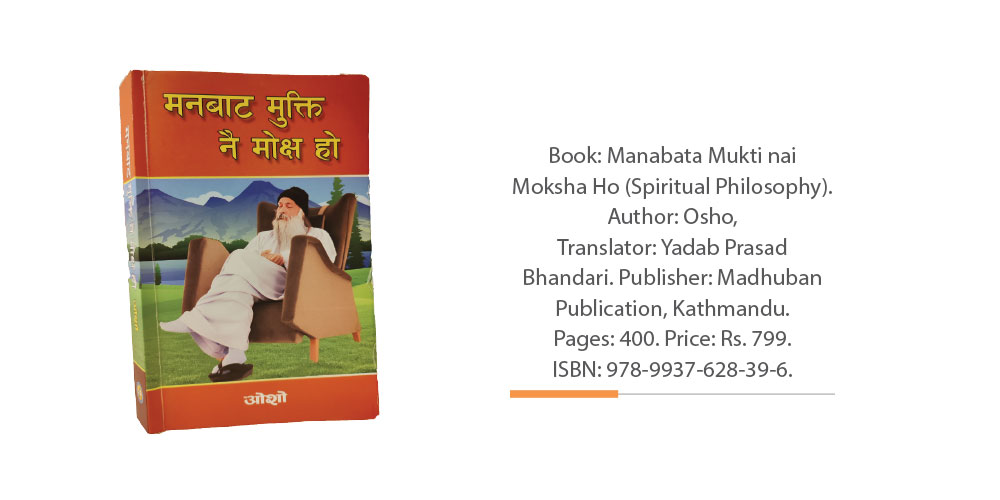

Osho authored dozens of books on these philosophical discourses, some of which have been translated into Nepali. Continuing this tradition, Yadav Prasad Bhandari has translated 'Manabata Mukti Nai Moksha Ho' (Freedom from the Mind is Salvation). This 400-page anthology of philosophical discourses, focused on human consciousness, mindfulness, and salvation, provides answers to the myriad questions one may have been pondering for a long time. Everyone seeks stability, peace, and mindfulness to be in harmony with nature and with others.

Osho often dichotomises various aspects of life, illustrating that the two parts are indispensable entities of existence. For example, we recognise something as good because something bad exists. This juxtaposition allows us to discern and appreciate each concept. Similarly, life and death are interdependent; life creates death. This idea extends to the lives of gods as well. Rama is revered because there was Ravana. If Ravana were removed from the Ramayana, there would be no 'Sita Haran' (abduction of Sita), no battle between Rama and Bali, no burning of Lanka, and no war—essentially, the Ramayana would not exist, and we might never have heard of Lord Rama.

Likewise, imagining Duryodhana missing from the Dwapar Yuga scene, there would be no gambling, no harassment of Draupadi, no exile of the Pandavas, and consequently, no Mahabharata. Without the Mahabharata, the Bhagavad Gita would not exist.

Osho uses these analogies to demonstrate that our experiences are complete only when we understand opposing views and knowledge. Conflict exists everywhere, and the mind generates conflicts over every possible idea and event. When an individual move beyond these conflicts or waves of thought, they can enter a 'no-mind' state, where concepts of good and bad do not exist. However, transcending conflict is an arduous task, as the mind constantly creates myriad 'consciousnesses' and takes pleasure in generating conflicts, even over trivial issues.

Osho says that conflict is the mind's sustenance. He compares the mind to a democracy where decisions are made based on majority votes, which can shift with every new election—sometimes within seconds. To avoid being enslaved by the mind, one must move beyond it. "Meditation is the death of the mind," says Osho.

Therefore, the mind resists meditation by finding countless excuses: it might be too early, too cold, you might be sick, have overtime work, need to attend a party, visit a friend, or post a video on social media—thus leaving no time for meditation. The mind obstructs transcendence. Remaining motivation often evaporates when one encounters a master who teaches complex methods like fasting, punishing the body, and painful postures.

The book contains 38 of Osho's finest essays on the mind, mindfulness, consciousness, transformation, the body, and God. Translated into Nepali from the Hindi original, Bhandari has captured the essence and flavour of Osho's ideas.

This book is a valuable addition to your office desk or bedside table. Whether you read it before starting your day or before bed, you will not regret it.

(The author is a journalist at The Rising Nepal.)

-original-thumb.jpg)