- Saturday, 7 March 2026

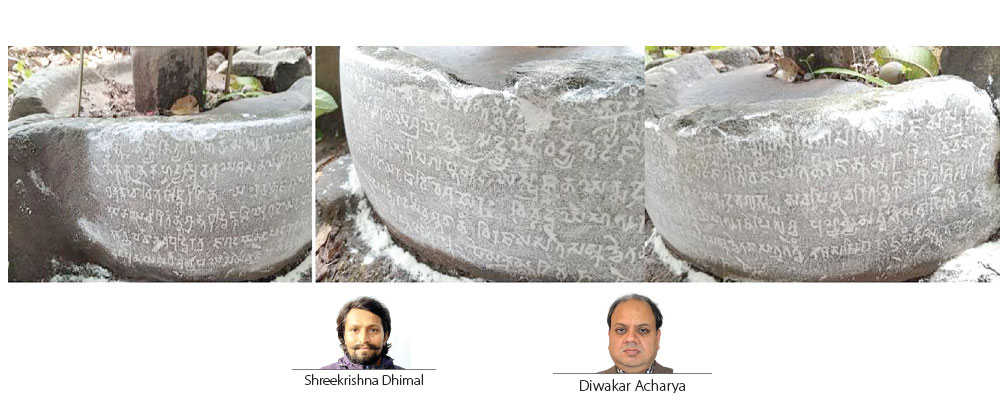

New Licchavi Inscription Discovered In Sindhupalchok

A new Licchavi inscription has been discovered in Mahadevtar, Ward No.10 of Indrawati (Bhot-sipa) VDC, Sindhupalchok. This inscription inscribed on the base of a Shivalinga, currently known as Tileshwar Mahadev, is dated in (Shaka) Samvat 442 (577 VS), the 5th day of the dark fortnight of the month of Pausha. Thus, it is from the time of King Vasantadeva but does not include the king’s name. Unfortunately, the inscribed base (jalahari) is broken into three pieces, and a few syllables are lost in five lines of this six-line inscription except in the last line. In two of these lines, lost syllables can be guessed and restored based on metre and context, but this is not possible in the rest.

This inscription, found outside the Kathmandu Valley in a place relatively distant and isolated, concerns a family directly involved in the running of the entire kingdom for centuries in the Licchavi period. It provides new information about this family and informs us about the problematic character and eventual demise of a member of that family at a young age.

The Text of the inscription

Here below is the entire text of the inscription: In the text, a tentative reading is placed inside (), anything we inserted is within [], a text reconstructed in the damaged part is within <>, and every lost syllable not possible to restore is indicated by ‘–‘. [line 1] svasti nityānityaṃ vimohaṃ saguṇam a[sa]guṇan nāyam antar nna (bā)[hya]m sūkṣmaṃ sthūlaṃ sthaviṣṭhaṃ vibhum avibhum ajaṃ sampra - - - - - [। ]

[line 2] naikan nānekam ādyam bhavabhayaśamanaṃ yogino yaṃ śrayante sa ddhyeyo vedyave(do) jagati vijayate nīrajaska[ḥ] smarāriḥ [। 1 । ]

vacasā(pi)

sa ca pitṛcaritañ cikīrṣur itthaṃ śiśur api - - - - - - - - [। ] [line 4] tam anayacaritan naśāntabuddhiṅ kaliyugadoṣa upāviveśa ghoraḥ [। 3 ।]

vivṛddhaye mātur atho pituś ca puṇyasya sarvvābhimatāptihetoś [।] (ca)[kāra] - - - - - - - - [line 5] tadartham evā(kṛśa)buddhir atra [। 4 ।]

jagadaghanudam ādyaṃ rodasī vyaśnuvānaṃ virajasam atamaskañ cetanāmātratatvaṃ [।] katham api bahurūpaṃ saṃ(stu)taṃ mokṣa

The inscription begins with a eulogy of Shiva as the enemy of the Love-God in Sragdharā metre. In the second verse, it praises Bhīmagupta as a man following Arjuna in archery and Yudhishthira in wisdom and speech. This should be the same Bhīmagupta who is mentioned in the Patan Swathu-Tol inscription of Samvat 411 (546 VS) as a Lord of a Province and the Great Chamberlain. The third verse provides an intriguing piece of information: Bhīmagupta had produced a son called Devagupta, who, though a child, always tried to imitate his father. In the course of this behaviour, Devagupta did something drastically bad, but we do not have any detail of that as the text suffers from the damage to the base of the Shivalinga. As the inscription states further, Devagupta was badly behaved and had no peaceful mind, and the dreadful defect of the dark Kali age entered him. It is not easy to guess what this defect was because we have not found a similar expression elsewhere.

This dreadful defect of the dark Kali age could be some stigmatised disease or engagement in immoral or revolutionary activities. Nothing more is said about Devagupta—the inscription is hiding something, and in the next verse we are told that somebody of mature and strong mind erected a Shivalinga and built a temple for the augment of the merits of his mother and father, fulfilment of desires all wished for, and particularly for the good of that person, Devagupta. This piece of information suggests that by the time of the installation of this Shivalinga, Devagupta was no more. He was already killed or had killed himself in this place, and this might be the reason that somebody who cared for him came this far from the capital of the Licchavi kingdom to install a Shivalinga.

The last verse of the inscription states that the donor built a temple of Shiva at this place for the sake of liberation of Devagupta, and describes Shiva as the one who destroys the evil of the world and pervades both heaven and earth, who is devoid of blemishes and darkness and exists as the pure consciousness, who is known as the multiform Bahurūpa, also as Bhava and Isha, devoid of evil, and whom people can somehow praise even though he is infinite and so unknowable. Thus, this inscription describes Shiva as both immanent and transcendent. Further, it is remarkable that it highlights Shiva as Bahuroop, which is alongside Rudra, the most important designation of Shiva in the older layer of the Pāśupata Sūtra. Thus, this inscription is important for the history of Shaivism in Nepal.

The name of the person who thus installed a Shivalinga for the liberation of Devagupta is lost in the damaged part of the inscription, but we can guess who this person can be. This cannot be Bhīmagupta, the father, because the inscription uses the past tense to describe him; he was no more. The wording of this inscription and description of the reality of Shiva based on the philosophy of difference and non-difference of the ultimate reality and the world (Bhedābheda) match the same in Anuparama’s Handigaun Satyanarayathan inscription. Therefore, this person can be Anuparama himself, the most intellectual and perhaps the most senior member of the Abhira Gupta family at that time. If not him, this can be Ravigupta, who was the Chief Justice and Great Chamberlain in the court of King Vasantadeva for a good time (570–589 VS).

In the Licchavi period, starting from the time of King Mānadeva, the family of the Abhira Guptas was only next to the family of the Deva king in terms of power and influence. Their family belonged to the lineage of the moon, whereas the king’s family belonged to the lineage of the sun. Licchavi inscriptions show that several Guptas held various offices under various rulers, but the most important and powerful family of this clan was the family of Paramābhimānin, alias Paramagupta. He had two sons, Mānagupta and Anuparama. Mānagupta was involved in royal administration, and he was the person who built Indradaha at the top of the Dahachok mountain, so tells King Jishnugupta, identifying himself as the elder brother of his great grandfather. Månagupta’s younger brother, Anuparama, was an intellectual, but we have no evidence of Anuparama holding any office. His Eulogy of Krishna Dvaipāyana Vyāsa, inscribed on a pillar in Handigaun Satyanarayanthan, is the most sophisticated composition found in Licchavi inscriptions, in terms of language, metre, and contents.

The history of the family branch of Mānagupta is not well documented, but Bhīmagupta, Devagupta, and Ravigupta are likely to have been part of this branch. Around Saṃvat 454 (589 VS), Ravigupta and other family members fell victim to a natural or unnatural calamity. Following this incident, Maharaja Mahasåmanta Kramalīla, who had been an ally of Ravigupta in his final days, promoted Bhaumagupta, a son of Anuparama, to oversee the royal administration. Bhaumagupta held this position for a significant period. After his death, Amshuvarman rose to power, during which time the Gupta family was overshadowed for a generation. Consequently, little is known about Bhaumagupta’s son. However, Bhaumagupta’s grandson, Jishnugupta, aggressively seized power after Amshuvarman's demise. He ousted Udayadeva, whom Amshuvarman had chosen as his successor, and ruled the kingdom himself, installing puppet kings from the royal family.

Vishnugupta, the son of Jishnugupta, enjoyed royal glory, but his son, Shridharagupta, who had already been named crown prince, never ascended to the throne. King Narendradeva likely destroyed the house of the Guptas while reclaiming his ancestral throne. At the end, people have recently floated different ideas concerning the interpretation of both eras used in Licchavi inscriptions, and there is a need for proper examination to settle this dispute. However, it is not possible to do so on this occasion, and we have assumed that the first era of Licchavi inscriptions was the Shaka era.

(Dr. Acharya is a professor at the University of Oxford, Dhimal is a journalist and archaeological researcher.)