- Friday, 24 October 2025

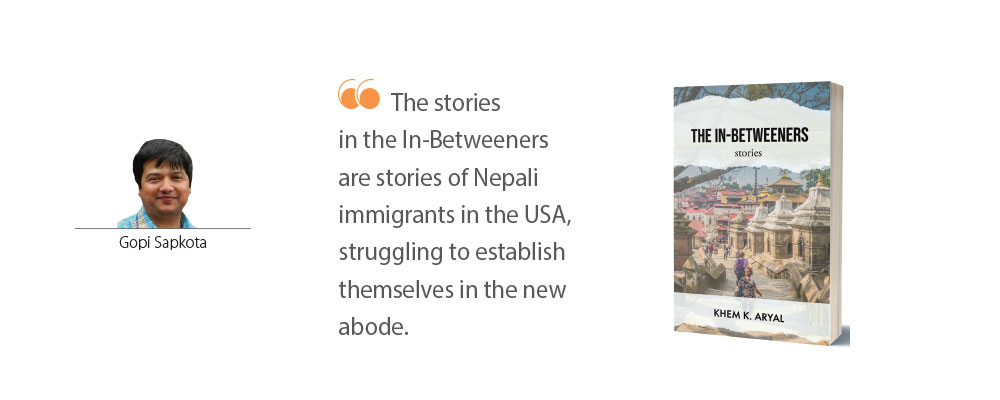

Khem K. Aryal’s In-Between Sway

It was 1995 or may be 1996. You tend to be forgetful, or you would not care, when you are over fifty. It does not really matter if you miss a year when you are counting the years from your past.

Having wandered on campus corridors for a while looking for my classroom, I recall, I entered Room Number 11, where some 30 or 40 semi-attentive students listened to a lecturer, whom I would later know as Anita Dhungel. It was my first day of class as an M.A. student at Ratna Rajyalaxmi Campus.

On that day, I didn’t know two things would happen in the future. First, out of those 40 unknown faces, I would find Nirmala and marry her; and second, I would make a decades-long friendship with Khem K. Aryal and write about him following the publication of his book in the United States, something we didn’t hope could happen to us one day.

In the last 27–28 years of our friendship, you can’t imagine how many hours we must have spent discussing writing, publishing, recognition, publicity, contribution to Nepali literature, and what not.

One day, during the early years of our friendship, one interesting incident happened. Khem invited me to his rented room for tea. It was a decent-size room, painted in light yellow, with a small book rack in a corner. When I was scanning the room, I saw a painting hanging on the wall over the book rack, signed by the artist as Kumar Shishir.

It was a familiar name to me. I asked Khem whether he knew the painter. He smiled and asked me back, ‘Do you know him?’ I said I knew him by his name, but I didn’t know him personally.

He smiled again, and I sensed that he himself could be the artist. I asked, ‘Are you the artist?’

He laughed, and then both of us did.At that point, Khem had already published a collection of Nepali poems under his pen name, Kumar Shishir. His stories were getting published in Nepal’s prestigious literary journals like Madhuparka and Mirmire.

As we were completing our master’s degree, I could see that he was getting more into English writing while I continued to write in Nepali, though I did write in English too occasionally. Both of us were getting more serious about writing while struggling to find a space in the literary landscape of Kathmandu.

It was an interesting period in Nepali English writing. After the restoration of democracy in 1990, new English publications and English-medium schools were burgeoning, and the demand for English writing and venues to share English writing were increasing.

Under the guidance of senior writers and professors, such as Padma Devktoa and Shreedhar Lohani, we founded an organisation, the Society of Nepali Writers in English (NWEN), in 2000 to promote English writing from Nepal.

Khem was nominated as its president, and I became secretary. This resulted in monthly meetings in which we mostly shared poems, the publication of Nepalese clay, and liaison with English newspapers to publish creative writing pieces in their weekly supplements.

These spaces encouraged writers to write in English as well as to translate Nepali writing into English. As president, Khem led the organisation’s efforts very effectively, and we remained close collaborators until 2007, when I migrated to the UK and Khem was planning to pursue his Ph.D. in the United States.

During those NWEN days, Khem’s two English poetry collections, Kathmandu Saga and Other Poems and Epic Teashop, were published in Kathmandu. He took the lead in publishing Of Nepalese Clay and co-edited it with Professors Padma Devkota and Hriseekesh Upadhyay for seven years. Most of the Nepalese writers writing in English were featured in the journal. The journal was also instrumental in grooming many new writers in English.

Samrat Upadhyay and Manjushree Thapa were our idols back then. Samrat’s debut short story collection, Arresting God in Kathmandu, which won him the Whiting Award, and Manjushree Thapa’s the Tutor of History were creating a big buzz among English readers in Kathmandu, which inspired all of us. We too dreamt of publishing our books in English from the United States or the United Kingdom one day, though that one day didn’t dawn anywhere on the visible horizon.

I decided at one point, though, that I would not bother about writing in English. I was making my space in Nepali writing, with books published from the Nepal Academy and Ratna Pustak Bhandar, which were considered top publishing venues those days. I continued to concentrate on Nepali writing, whereas Khem continued writing in English.

His dedication, passion, and belief in himself have finally led to the publication of a collection of his stories, The In-Betweeners, by an American publishing house, Braddock Avenue Books, and that makes me feel that the dream we shared long ago has come true. I cannot be happier for him and for Nepali writing in English as a whole.

The number of Nepali writers writing in English is growing, both within and outside Nepal, but we have yet to see writers of significance since Upadhyay and Thapa. I genuinely hope that the publication of The In-Betweeners will be just the beginning for Khem.

Khem is a happy person in life, but when it comes to writing, he is never satisfied. The time and effort he invests in editing, crafting, and revising amazes me. It seems that he enjoys the process of writing more than the writing itself. I am envious of his patience in waiting for the publication. I remember that a novel he wrote about twenty years ago was accepted by a small publisher in Delhi, but he stepped back and never got it published.

In terms of subject matter, Khem deals with socio-political and family issues. He picks up simple but somehow weird characters from society, observes and examines them closely, and crafts their stories in carefully designed plots with artistic details, most of the time playing with their ambivalent mental states.

On the surface, the stories in The In-Betweeners are stories of Nepali immigrants in the USA, struggling to establish themselves in the new abode while still thinking of their life back in Nepal. However, you delve into them more, and the stories will open new windows to understanding human predicaments in general.

I feel that these stories are more than just the stories of in-betweeners, or they make me feel that all of us are in-betweeners. They deal with human weaknesses and resilience, and they deal with the personal and social absurdities we are all part of.

Khem’s stories are unique as they deal with seemingly mundane issues that most of us don't even think of writing about. While reading some of his stories, you may get irritated with his characters and feel like shouting at them for not sorting out even a minor problem.

The main character in “Shopping for Glasses” suffers for a long time simply because he is unable to decide which frames to choose and the shopkeepers are not forcing him to buy any, unlike in Nepal. The stories feel so deep that readers will find it hard to come out of the fictional well that the writer has dug. I think that’s the success of a writer. I wish The In-Betweeners a big success.

(Sapkota is a poet and playwright.)