- Friday, 21 November 2025

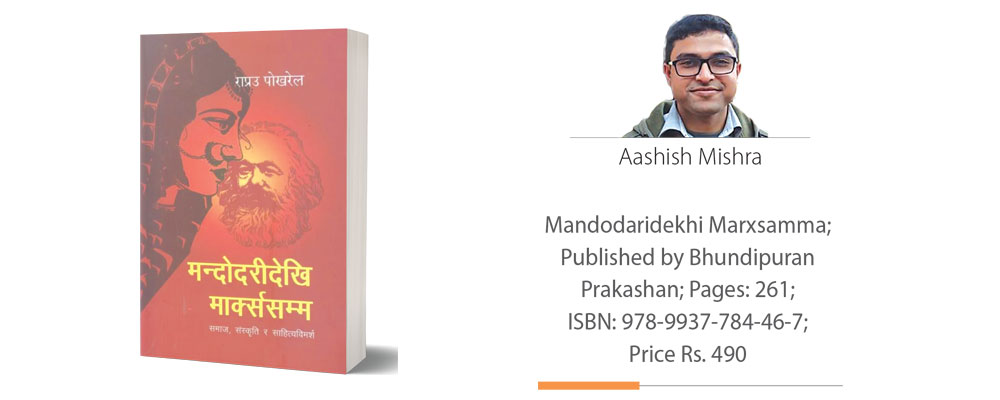

Mandodari, Marx And Everything In Between

If there is one thing the book ‘Mandodaridekhi Marxsamma’ reveals about its author, Ramji Prasad Upadhyaya Pokharel (RaPraU Pokharel), it is that he is fearless. He wants to take the road less travelled, go against the grain, and call people out, and he does not care what others think of him. Some may call this honesty, while others may perceive it as vanity, but a thorough reading of the book suggests that this fearlessness could stem from Pokharel’s commitment to his readers.

Pokharel wants to present perspectives others shy away from. He wants to shed light on concepts and notions that people do not seem to be getting from other sources. At least that is how it appears in ‘Mandodaridekhi Marxsamma’.

The book has 23 chapters divided into six sections. The first section focuses on exploring BP Koirala, or BiPra Koirala, as a poet. While many choose to infer political meanings from Koirala’s literature, Pokharel has done the opposite and sought to analyse the literary qualities of his political ‘Jail Journal’.

Even within the literature, reviewers seem much too content with celebrating Koirala’s exceptional writings and do not seem to adequately acknowledge his talents in critiquing. Pokharel seeks to fill this gap through Section 1 of this book.

The second section is about the late Madan Mani Dixit. Here too, Pokharel dives beneath the surface, going beyond what is popular to the heart that readers may not have even known they needed to see. Pokharel does discuss Dixit’s Madan Puraskar-winning novel, ‘Madhavi.’ It would have been remiss of him if he had not. After all, it is the work Dixit is best known for. But he also puts the spotlight on Dixit’s other masterpieces, ‘Bhumisukta’ and ‘Hamra Prachin Nari’.

After reading this section, one cannot help but feel that Pokharel is worried that Dixit has been boxed, that he has been defined by ‘Madhavi’ and ‘Madhavi’ only—a work that the late author is on record as saying is not his best. This worry would be natural, though. Pokharel and Dixit were close friends. ‘Mandodaridekhi’ starts with an article Dixit wrote for the Janajagriti Cultural Club of Mahottari in 2008 in which he gets candid about the value Pokharel held in his life and the important role he played in the development and publication of ‘Madhavi’. Section 2 of Pokharel’s book is perhaps an ode to this eminent personality, who sadly left the world in 2019.

Section 3 is a portion dedicated to exploring the historical and religious foundations on which the present Nepali society is based. Of particular note is Pokharel’s chapter on Brahmanism, where he separates the ‘ism’ from the ‘Brahman’ and criticises it for its application by the elites of society, whatever caste they may be, for their benefit.

Section 3 and Section 4 together justify the title of this book. Section 3 characterises the Ramayana’s Mandodari, and Section 4 contains a chapter on what the writer calls democracy and present-day Marxism. Pokharel builds upon these sections in the Appendix, where he interviews writer and researcher Sujit Mainali for a chapter headlined ‘Communism does not translate to Samyavaad in Nepali’. As stated earlier, Pokharel does not hesitate to go against the grain. If this book is any indication, he seems to thrive in it.

But this book is not without its flaws. The six sections appear disjointed and without flow. That could be because they deal with different subjects, but the author could have done a better job of maintaining coherence. The casual reader looking for an easy bedtime read may struggle to find an overarching narrative.

Also, Section 5 and its chapters ‘Janamatkaa Pravartak Prithvi Narayan Shah’ and ‘Swapnadarshi Raja’ appear to have been motivated by the personal adulation of kings Prithvi Narayan Shah and Mahendra. Both rulers deserve legitimate praise for their contributions to the nation, but they also need to be judged for their failures. ‘Mahendra Nationalism—taking the term away from biased political debates and putting it into a social perspective—was an exclusionary idea that was intolerant of diversity and an attempt at anchoring the nation to the monarchy (to secure the latter’s future) rather than to stable and decentralised institutions.

Analyses are, by their very nature, not objective. They are the interpretation of facts and events within specific frameworks. Sections 1 to 4 place ‘Mandodaridekhi’ within a framework of detached discourse. As mentioned above, Pokharel does not pay heed to what others have said and intends to provoke the readers to question why they think the way they do about society, culture, and literature. Section 5, though, appears to veer off this path. In trying to counter the political narrative of ‘The kings were all feudalistic oppressors who held Nepal back for centuries’, the author peddles a ‘The kings were true patriots and denouncing them is akin to siding with foreign conspirators’ message. The last 15 years since the abolition of the monarchy have proven both of these assertions wrong.

‘Mandodaridekhi Marxsamma’ is undoubtedly an arousing read, offering new insights into familiar people, writings, and notions. The writer knows how to describe without preaching and keeps explanations light and concise. Like in his previous works, ‘Sarvadharma Sambhav’ and ‘Bichar Mimamsa’, Pokharel does not just spout his beliefs but justifies them through rationale and evidence. Yet he does it humbly. The writing reflects a man who does not treat his word as law and is open to suggestions.

(Mishra is a journalist at The Rising Nepal.)