- Saturday, 18 October 2025

Demographic Shift: Rising Elderly Population In Nepal

The age structure transition in Nepal reveals a constant rise in the elderly population and a decline in the number of children. The pattern over the past seven decades shows this. When a nation transitions from a high to low mortality and fertility rate, the proportion of children falls, and that of the elderly rises. The transition to low mortality and low fertility takes a long time. Worldwide research has demonstrated that while fertility drops gradually, death declines more quickly in the years between. The decline in mortality is largely attributable to the development of health care over time. Humans have the innate desire to live longer and be healthy. As a result, they happily accept any inventions, drugs, or services that extend their longevity. But in the case of fertility reduction measures, it is not as easily adapted as in the case of mortality reducing measures. Thus, in between, rapid population growth takes place, and this phenomenon is recognised as a demographic transition. Demographers know best, but a cursory analysis of Nepal’s population data for the last seven decades clearly shows that Nepal is almost in a low fertility and low mortality state and is on the verge of an old age crisis.

Demographically, the good news is that there is a huge proportion of the ‘economically active population—aged 15 to 59 years at present. A total of 62 per cent of Nepal’s population belongs to this category. This large concentration is also referred to as a "demographic dividend.'' In absolute terms, this figure is encouraging and represents the golden age of national demographics. But this stock is useful only when the nation is equipped with suitable instruments and programmes to utilise it. This group must be engaged meaningfully, and the only way to keep them engaged within the country is through employment generation. But recent labour migration figures and figures on the no objection letter clearly show that the good news of the "demographic dividend" is more of a statistic for popular consumption than to translate it into action.

Another good news about this age structure transition is an increase in life expectancy in Nepal. Life expectancy at birth has reached 73 years for females and 70 years for males, according to the State of the World Population 2022. This is remarkable progress.

According to the Central Bureau of Statistics, the corresponding figures were 61 years for females and 60.8 years for males twenty years ago (2001). Both of these messages have implications for the ageing population in the country.

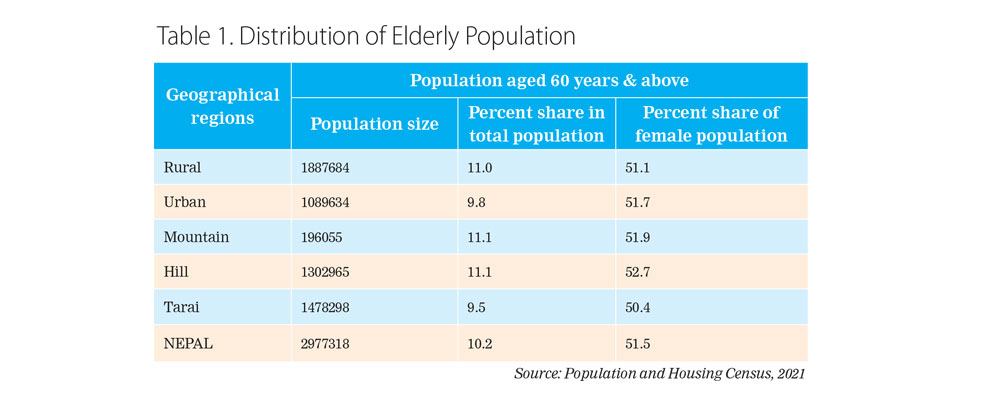

Nepal's policy documents concerning old age categorise individuals aged 60 and above as elderly, as evidenced by the Population and Housing Census 2021, which tallied 2,977,318 people falling within this group, comprising 10.2 per cent of the total population. Of these seniors, 51.5 per cent are female, while 48.5 per cent are male. While many developed nations consider 65 years as the benchmark for classifying someone as elderly, it's worth noting that females typically outnumber males within the elderly population. This trend is mirrored in life expectancy data, where females consistently exhibit higher average longevity than males. For instance, in 2022, the global average life expectancy for females stood at 76 years, compared to 71 years for males.

Trends of growth

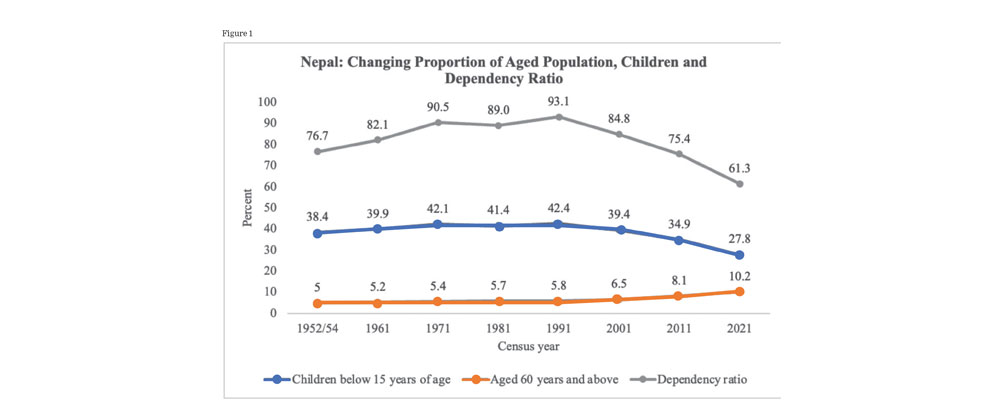

In Nepal, one out of ten is an elderly person. Generally, developed countries are characterised by a high percentage of elderly population and a low percentage of children. Though a least developed nation, Nepal has already shown advanced demographic signs. Figure 1 shows the trend in population in three important indicators of population, namely, the population 60 years of age and over, the proportion of children below 15 years, and the dependency ratio.

Changes in their proportion over time demonstrate the growing trend of Nepal’s population. First, the indicator population aged 60 years of age and over has shown a consistent, relatively steady increase until 1990 and rather a speedy increase onwards. It took four decades to increase from 5 per cent (1952–54) to 5.8 per cent in 1991 showing a 4 per cent increase per decade. Between 1991 and 2001, the increase was 12 per cent. The consecutive decennial increases for 2011 and 2021 were 24.6 per cent and 25.9 per cent respectively. This proportion may seem small, but the absolute size and trend of increase are very significant.

Between these years, whereas the total population increased by 3.5-fold (from 8,256,625 to 29,164,578), the population of the elderly increased by 7.2-fold (from 412,830 to 2,977,318). When these figures are contextualised in terms of who looks after their living conditions, health, and welfare and what the state offers them, the picture is worrisome.

Second, the proportional share of children in the total population shows some ups and downs, with a consistent increase for the first four decades, reaching 42.4 per cent in 1991—an increase of 10.4 per cent. This figure is indicative of high fertility, and the annual growth rate of the population was 2.1 per cent between 1981 and 1991. Since then, there has been a rapid decline in the proportion of children in the total population. Children’s share in the total population decreased to 27.8 per cent in 2021, an all-time low. This is a significant age-structure change, indicating a very rapid change in the total fertility rate and number of women having children. More importantly, this drastic change in the last decade warrants serious discussions on what the future holds for the country and the continuity of its population and society. It is too fast a decline.

Third, the dependency ratio, reflecting the burden of dependency on the productive population, presents an overall positive picture over time. The ratio reached its highest in 1991 and decreased to an all-time low in 2021.

This is good, but this decrease is primarily due to a decrease in child dependency, and elderly dependency has been continuously on the rise.

Between 1991 and 2021, the old-age dependency ratio increased by more than 47 per cent (11.2 per cent to 16.5 per cent). In the meantime, longevity is on the rise, increasing elderly dependency.

The differential level of dependency burden is such that children graduate from being dependent to the productive population, but the older ones remain in the same category as long as they survive.

Regional dimension

Ageing is a nationwide phenomenon, and nearly 30 thousand people in Nepal are elderly. However, ageing is more serious in rural areas than in urban areas (Table 1). First, the proportion of the elderly is 11 per cent in rural areas, whereas it is 9.8 per cent in urban areas. Second, whereas only 33.8 per cent of the total population lives in rural areas, 36.6 per cent the elderly population lives there. Third, the proportion of the population absent (both within the country and abroad) is 13.7 per cent in urban areas and 18.3 per cent in rural areas. This higher absenteeism in rural areas has implications for elderly care at the time of need and reflects ‘empty nest syndrome’ for the elderly, especially in the hills and mountains. The distribution of the elderly also shows a regional and gender dimension. The mountain and hill regions have a higher proportion of elderly people than the Tarai. Likewise, in all the regions, the share of elderly females is high, and more so in the hill region. More importantly, the proportion of elderly females is higher than that of males, except in the Tarai.

In conclusion, the growth of the elderly population is a normal occurrence, but what is important is the context in which this population is growing. A large proportion of the elderly population below 70 years old is active, but the majority of the elderly are unlikely to remain economically active, and those are the ones to suffer. First, the family context is not encouraging. Early separation and nucleation are taking place. The household size has gone down to 4.4 people in 2021, compared with 5.4 in 2001. This figure is 4.0 only in the hills. The Department of Foreign Employment records more than 771 thousand adults to have left the country for foreign employment, and the Education Ministry records more than 100 thousand obtaining no-objection certificates for study abroad this year. This is not a welcome phenomenon.

Ensuring desired support

Labour migrants may send remittances, but many elderly people need support not necessarily from the purse but from their hearts and physical presence. Elderly people are costly. The national context is also not favorable. Many of them need special health care that goes beyond family support.

Shifting the national health budget towards curative measures and the elderly at the cost of child health and preventive measures may not be easy for the government when the national and health budgets are under stress.

Moreover, Nepal’s current economic scenario, such as GDP per capita ($1,337), the national debt (US$ 9.1 billion), the trade deficit (NPR 921.16 billion with India only), and the average economic growth rate (< 6.0 per cent) does not indicate a favourable environment for the elderly in the immediate years. The outcome is that neither the family nor the state are in a position to ensure safe, dignified, and healthy living for the elderly in Nepal. The National Elderly Policy under consideration is expected to move forward from a mere welfare approach towards a rights-based approach so that a healthy ageing-oriented environment is created in society.

(The author is former University Grants Commission chairman.)