- Friday, 20 June 2025

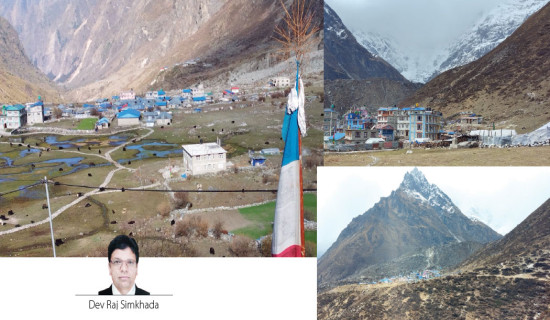

Mesmerising Mustang's Calling

Between two giant crimson rocks stands a small window to a mythical and mesmerising world. In fact, it’s an orifice resembling what we call a Khopo in parts of western Nepal, including Gulmi.

First, let’s enter into this small world of Khopo and what it contains—or used to contain in the good old days.

A Khopo is a hole, mostly in the inner wall of a traditional house made of mud, stone, timber, and a roof made of slates, zinc sheets, etc., for safely storing things like a bowl of pudding for eating the next day (in other places, there’s every chance of a stray cat on the prowl finding it and feasting on it), rolls of thread with needles inserted in them, a bowl containing mustard oil, rolls of cotton for making wicks, and so on. It’s no rocket science that such holes are closed from the outside to block cold wind inside and prevent pests like rats from entering the house and wreaking havoc.

A Takhato will scream injustice for not talking about the important place it holds—or used to hold—in traditional houses that used to dot our home village. It is a built-in rack just above a traditional window made of wood.

In our small world, in those bygone days, French windows were not necessary. The idea behind the windows was to let in the sun and the wind (a little bit) and let the smoke from fuelwood burning in the hearth out.

For that purpose, a small window consisting of small holes, horizontal bars, or two wooden flaps would suffice, especially in a small, usually three-storey house.

A bit of ingenious natural weather conditioning, me thinks, at a time when climate change was not even on the village's horizon. In fact, when the first motorised vehicles—tractors, buses, and jeeps—came rolling, engulfing villages in clouds of dust, there were rumours that they—and not suitable weather conditions—brought mosquitoes too.

In hindsight, one wonders if those windows served another purpose in ancient times: keeping a close watch on who has entered your premises—a friend or a foe—without the guest/intruder seeing you. Historically, Nepal has been on its guard as it has fought many a war to keep its sovereignty intact. Such a level of security sensitivity is hard to find these days.

Those windows gazing at the outside world in idyllic villages with mixed emotions may not be as beautiful as the ones looking at sprawling courtyards in cities and towns, but they reflect our defence and security sensibilities nonetheless. Etched in time and hanging, Tuino comes next. The word sounds like Tuin, a dangerous lifeline used even for crossing raging rivers and streams in Nepal in the absence of bridges. During our childhood, Tuino would be used for hanging clothes.

Hanging not so far away from the smoky hearth, imagine the ordeal the good ole Tuino must have gone through along with clothes clinging onto it. And imagine the toll the smoky hearth must have taken on family members, particularly mothers, daughters, and daughters-in-law, who had to spend hours cooking for the family and cattle too.

Back to the crimson rocks and the tiny opening. Through that hole, the rays of the sun stream in, illuminating a magical, mythical, and mystical world. Through the same hole, a river leaves for you don’t know where and for what. Leaving such a wonderful place just like that—like lakhs of outbound youths—must be very hard. The rivers must have shed an ocean of tears before leaving mountains, terraced fields, and fertile flatlands like our youths, right?

Alas, like those bygone days, those traditional houses that blended so well with local landscapes won’t come, and with them, a part of our heritage will be lost forever, thanks to a frenzy to build modern houses out of fear that such houses won’t be able to withstand fresh jolts in an earthquake-prone country.

Before they vanish, our government authorities—at the centre, provinces, and local levels—should work out ways to preserve them by spending on research, just to make sure that the traditional architecture stands the taste of time, with a little bit of physical and technological reinforcement measures, if need be.

The magical, mystical, and mythical world of Mustang recently came to life in Kishor Kayastha’s photo exhibition titled Mustang, featuring 30 panoramic stills highlighting a rich and serene interplay of art and technology amid a musical ambience. Snowy mountains, serene monasteries, sparse vegetation growing in the snow, and even Himalayas bereft of snow and baring black rocks due, mainly, to climate change offer glimpses of Kayastha’s two-decade-long romance with Mustang.

Mining Khopa and Takhta built deep inside the cranium, and dusting off memories, including shots taken at the exhibition organised at the Nepal Art Council Gallery from January 7 to January 19 in partnership with the United States Embassy and DHIMAL Foundation, this scribe tried to paint a picture of Mustang and of his home village located on the lap of Mother Nature and Father Sky.

But Mustang is beyond the rusting words and memories of this scribe; it is beyond the interplay of light, angle, perspective, and mood. A lifetime is not enough to understand Mustang, leave alone this beautiful country, but Kayastha is at least on a journey to understand the place better. As for yours truly, he has not even embarked on that journey. For lakhs of uninitiated like him, a photo exhibition featuring the wonders of Mustang can be a good start. Two decades ago, Mustang came calling, Kayastha responded, and that has made all the difference. Mustang—and Nepal—is calling once again. Who are ready for the journey?

(The author is a freelancer.)

-original-thumb.jpg)