- Saturday, 31 January 2026

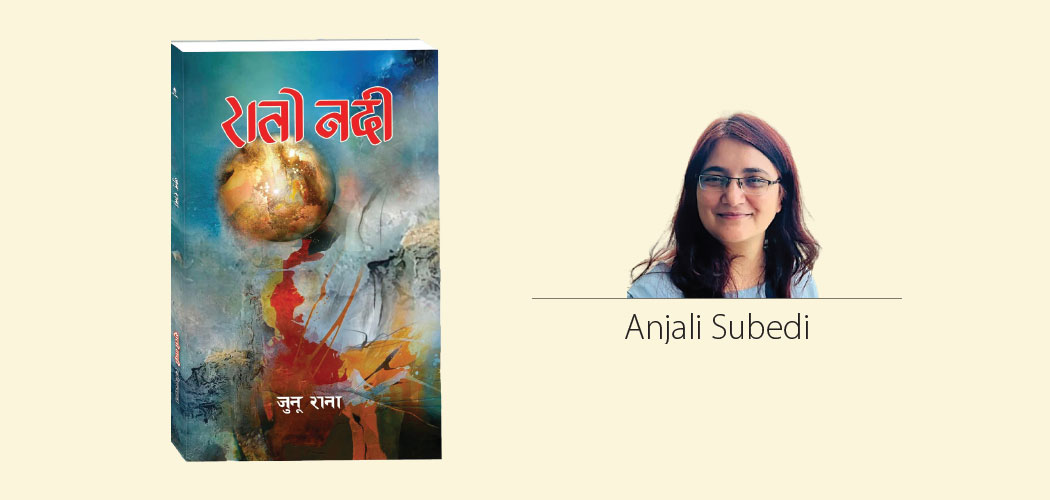

Songs Of Life And Periphery

Her perspectives are engaging. Her outlook is vast. Her senses fathom so deeply. Be it about life, death, love, or other battles in the human world, Junu Rana leaves a profound impact on readers through her debut poetry book, 'Rato Nadi'. Both in terms of the choice of themes and expression, Rana quite captures attention.

It's not a thread, but no less fragile, and breaks

It's not an ocean, but it gently endures hurricanes

It's not a political force, but it is its own opponent

Rato Nadi offers those lines in a poem called 'The Heart'. Though it is one of the most common subjects in poetry all over the world, her style does give a fresh touch. The strength lies in her ability to transfer her feelings to readers effortlessly. Neither too assertive nor too indifferent, Rana's approach feels just quite gentle. For instance, a poem called 'absence' is likely to make anyone go nostalgic over their beloved's memories. It teaches acceptance. Similarly, a cuckoo bird makes the poet think that its sweet call 'cuckoo-cuckoo' is just for its beloved, and the bird sings in despair—How I wish I had not loved anyone!

Ma Berang Rang ('I'm a colourless colour') meanwhile portrays the poet as someone who is deeply wounded by the division humans have carved for themselves just to practice hatred and discrimination. Shunyawadi (Zero Hour) gives goosebumps as it counts some weird failures and heartbreaks humans go through and declares, 'Oh human, you are just an illusion!' Similarly, in 'Ma Gayepachhi' (After I'm gone), the poet wonders about the possible pathetic condition of her most coveted belongings after she bids the last goodbye to the world.

This book was released at the end of June, and general feedback suggested it to be a revolutionary voice against patriarchy and other sources of discrimination. Since the writer happens to be female, she was promptly labelled as a poet who best outcries against suppression, oppression, and feminine woes. The title of the book, Rato Nadi, for the poem being about menstrual blood and stigma, also led to the assumptions. But the book is, of course, not just an additional feminist flag in the market. It caters to humans from anywhere in the world as it touches from general to deepest human cores.

Chests are in the queue, of different sizes and shades

From hundreds of them, only a few are to be selected, and sold

And the title of 'Bir Gorkhali' , the successful chests uphold

The legacy of ancestors, how can a Lahure disown!

And the mundane journey just goes on

Those lines from Lahure, one of the finest poems in the book, can have a universal appeal, for it has to do with the story of an army, youth, dreams and defeats, or irony. While the term Lahure in Nepal boasts of prosperity, heroism, or similar connotations, and 'Bir Gorkhali/Brave Gurkas quite commands respect in the world for the army's unparalleled performance, this is indeed equally a tale of our meagre choices, tears, and helplessness.

Most of the poems in the book, whether the subjects are unique or regular, work for reads due to adequate uses of analogies, metaphors, and imagery. While doing so, it unfolds different cultural and social dynamics of the Nepali indigenous communities.

The poems are, however, weak in terms of diction. The freestyle writing feels too ordinary or artless, more so in a few particular poems. The likes of Badipahiro (Floods and Landslides) and Baba (Father) feel too plain to be appreciated. Likewise, not every poem has justified the length. Taking more time for the final touch and selecting fewer of the poems in the list would fix those setbacks and save readers from visiting some tedious pages and lines, unlike below:

Oh dear life, I never asked you, if you're doing fine

What you love to do, what you love to dine

Whether you prefer to be a rainbow or a faded cloud

Whether you wanted to make friends or hated the crowd

Now I shall understand the universe of your existence

And follow your path, your aspirations

Those lines from Jindagiko Naam Ma (In the name of life) quite give food for thought as the poet begins to talk to the life itself and wonders if the journey ahead should be a more conscious one aligning with the inner light. Poems like Nun (Salt) that talks of the connection between livelihood, scarcity, necessity, and subsequent migration of the masses from Nepal's rural mountains to sophisticated areas in the past, Abhav (Paucity) that elaborates how humans always feel deprivation of one or the other thing, and Siru Jhar (Grass), where the poet projects the tiniest creatures as a reflection of the supreme energy, are equally smooth and meaningful. In the course of incorporating social contemporary issues, Rana has not forgotten the brutal murder of six youths in Rukum in 2020. 'Bheri Sakshi Chha' (Bheri is the witness) is there to remind the Nepali society of the height of inhumanity triggered by caste and class division and socio-political plights and power surrounding it.

If poems shall mean meeting a world of purity, gentleness, detachment, or a saintly abyss, Rana does come around it with this debut collection. She observes, wonders, questions, and narrates to leave readers equally sensitive and empathetic about the human world around and within. In this regard, Rana, who is not a new name in the media for her regular articles on contemporary issues, can fairly be regarded as one of the sharpest social leaders the country desperately needs.

(The author is a freelance journalist.)