- Sunday, 2 November 2025

Dashain Special

Dashain: Then And Now

Dashain itself is a thrilling word, evoking excitement not just for children but for grownups and the elderly. It brings pleasure to people of all ages, yet the joy is especially evident in children. Their happiness is apparent once the Dashain holidays begin. When we were children, the excitement would start weeks before Dashain, especially when the tailors arrived at our home to sew new clothes for the festival. Although today’s children no longer have to wait for Dashain to wear new clothes, eat meat, or enjoy beaten rice, it wasn’t the same four decades ago. Back then, children in the villages had the chance to wear new clothes—usually school uniforms—and savour meat and beaten rice only during Dashain. I was one of those children in Ilam in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

Dashain—the word itself was enough to make us happy, not only because we got holidays and new clothes but also because we were actively involved in various activities associated with the festival, something today’s children utterly lack. Although we were small schoolchildren in the fifth or sixth grade, we helped our parents and villagers collect red and white clay to paint and decorate the house, clear weeds from footpaths, and gather babiyo (grass used for making ropes) for swings.

Collecting kamero (white clay) was the most tiring task, yet we enjoyed it. We had to walk for two hours, traversing steep paths to reach the white clay mine, and then return home carrying a heavy load of wet clay in bamboo baskets. Surprisingly, all the villagers collected the white clay from a farmer’s private land without paying. Of course, at that time, village people weren’t money-minded or politically divided.

Being in a group of 10 or 12 and passing through the local Limbu community's graveyard, crossing two streams, was an exciting experience. The only thing we feared was the possibility of seeing skeletons unearthed by landslides in the graveyard. After bringing the white clay home, we used to whitewash the outer parts of the house with it with the help of brooms, while my mother used to paint the inside walls with the red ochre. It was also the mother's duty to polish the floors with cow dung. But these days, no one uses white clay to whitewash their houses. Lime has replaced it.

In the Rai and Limbu communities, the people used to make colourful pictures of different flowers on their whitewashed house walls, but making such pictures in the house walls of Brahmins and Kshatris was not allowed. Old Brahmin and Kshatri men and women used to say that making pictures on walls was a bad omen. However, some Limbus stopped marking Dashain and whitewashing their houses for a few years immediately after the political change of 1990. But now they mark it as usual.

Preparing chiura was one of the major tasks, primarily done by women. Back then, there was no practice of buying chiura from the market, especially in Brahmin and Kshatriya households. Village women would take turns making chiura in the traditional wooden mill, called a dhiki. Since at least four people were needed to operate dhiki, they often sought help from neighbors. They also shared the same utensils to wet the paddy for making chiura, as each household typically prepared at least 30 kilograms of it.

The process usually began around 3 a.m. and continued until 5 p.m. Since watches

were uncommon in villages, women would rely on the stars to tell the time. "We started preparing chiura after the 'Three Ankhe' (Orion's Belt) rose and finished in the evening," my mother would say, reflecting on the process from 45 years ago.

Nowadays, she only makes one or two kilograms of chiura to offer to the goddess and for our 94-year-old grandmother, who refuses to eat chiura bought from the market. The entire village used to be full of sounds—Tyangryang, Tyangrang produced by the wooden mills once the villagers began preparing Chiura.

However, the children had to wait until the day of Maha Ashtami to eat chiura, as it was only consumed after being offered to the Goddess in the morning.

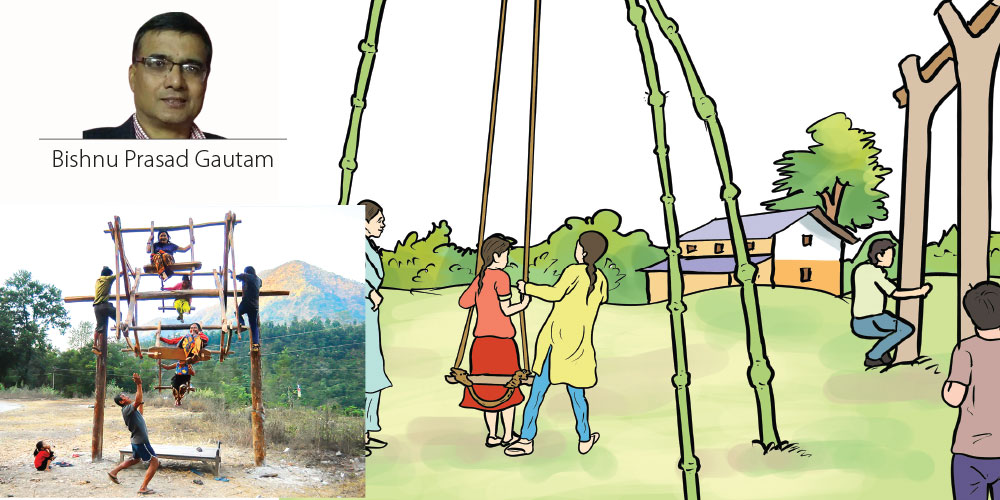

Setting swings were the primary tasks of men. Back then, there was a tradition of making linge and rote swings. In some places, people would also construct round (charkhe) swings.

The linge ping was made using four tall, strong bamboo poles, which were erected at equal distances, with their tops yoked together, and a long rope hung from the yoke for swinging. Four strong men could prepare this swing in about three to four hours, while in the evening, they would weave the rope using babiyo, which children like us helped collect.

However, making a rote ping required more time and effort. Strong men from the village would cut down two trees to use their trunks as the pillars for the rote ping and carry them from the forest to the construction site.

In addition to the pillars, they had to prepare a sturdy beam and eight "hands." They also needed to craft four seats and wooden arms to hang the seats. Villagers would build a rote ping using locally available materials, without even using iron nails.

The rote ping would usually be ready by Fulpati Day. But, the practice of building rote pings gradually faded away after the Maoists launched their armed revolt in 1996.

Normally, people gather at the rote ping on important days during Dashain and Tihar, such as Fulpati, Tika, and Purnima. These were also the places where many Rai and Limbu youths met their future life partners, serving as dating spots for the young people of these indigenous communities. Between Ghatasthapana and Fulpati, people also found time to clean the footpaths in their areas to ensure that those visiting relatives wouldn’t have to deal with the morning dew.

Preparing meat was another significant task. The Rai and Limbu communities would slaughter a buffalo in groups in an isolated location on Fulpati, sharing the meat among themselves. Similarly, Brahmins and Kshatriyas slaughtered he-goats on the day of Ashtami, while the Rais and Limbus killed pigs on Nawami. This tradition remains intact today.

Ultimately, the day of Vijaya Dashami would arrive, and we would eagerly put on our new clothes before receiving tika from our elders at home. After receiving tika, visiting mamaghar (the home of our maternal grandparents) was another exciting moment. Children still love going to mamaghar because they receive not only love but also dakshina (money) as part of the celebration.

In recent times, with our culture increasingly influenced by Western traditions, some people have, knowingly or unknowingly, begun giving less importance to Dashain. Instead of celebrating at home, they tend to embark on pilgrimages during this annual festival.

Dashain is, after all, a time to worship Goddess Durga for nine days and receive or offer tika, the prasad of the Goddess, at home with family. But when we choose to be away from home during the festival, we are not only neglecting the essence of Dashain but also diminishing the festival itself.

(Gautam is a chief reporter at this daily.)