- Sunday, 25 May 2025

First Mt. Everest Ascent: Notable Triumph Of Mankind

This is a majestic land. It’s mystical. It’s Nepal. It was a theatre of some improbable acts of human spirit and skills where the whole world was keeping an eye for a miraculous play of bravery. The year was 1953.

One of the biggest turning points in the history of mankind's bravery and skills was the ascent of Mt. Everest. It threw Nepal in the global limelight. For ages, Mt. Everest stood as the testimony of mankind’s daredevil imagination. The year 1953, a year after the Olympics in Norway and Finland, two finest gentlemen from New Zealand and Nepal were braving their way up into the thin air of Everest. Their triumph proved to be a major cultural turn in climbing history.

Being a relatively new democratic state in the aftermath of World War II, Nepal’s foray into statehood has been marked by socioeconomic uncertainties. The euphoria of the ascent of another 8,091 meters, Mt. Annapurna in 1950, got the country into top calibration and celebration too after the Everest saga. While the tiny Himalayan nation was caught in its own political struggle, its friendly citizens continued to look up to the mountains as a metaphor for life’s pursuits amid the global political chaos of the Cold War era.

While Nepal was caught napping in its own imagination of a sought-after destination for new-found global limelight, the British regime was contemplating long for a universal claim for conquering the mighty and improbable challenge of climbing the summit of Everest. The British Empire, whose supremacy was waning in the emerging post-World War II global order, had already financed eight unsuccessful expeditions to Everest. But the ninth expedition was a different story.

It was 1st June 1953, the eve of a historical day in London. The stage was perfectly set for the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II. The news of the first-ever conquest of Mt. Everest reached war-ravaged London from the rugged land of Khumbu. When Tenzing and Hillary reached the summit at 11:30 a.m. on May 29, their feat was a source of pride for the whole empire. Britain had proved itself great once again. In the declining years of the Empire, when Britain’s suzerainty was hitting its low ebb, this sporting supremacy helped Great Britain in its renaissance of self-image after the thirty years of war.

On May 30th, Hillary and Tenzing descended the Lhotse Wall into the fabled Western Cwm below Mt. Everest, and the British team learnt for the first time about their success on the climb.

James Morris, the Times newspaper correspondent, wrote a coded message and descended foot down on the Khumbu Icefall basecamp. He sent the news to London the day before coronation day and detailed that the summit had been reached and identified who the summiteers were by runner’ to Namche Bazaar. They detailed that the summit had been reached and identified who the summiteers were. On coronation day, on the 2nd of June, the newspapers were full of the Everest success. “All this and Everest too!”

The astounding serendipity of the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II and the first ascent of Mt. Everest by the British Mt. Everest Expedition in 1953 was uplifting and marvellous news, particularly given the times just eight years after the end of the Second World War, leaving a war-ravaged Europe and a crippled global economy. There were reasons to celebrate coming from the tiny Himalayan nation that had long cherished the friendship with Britain.

As Britain and the world prepared for the coronation on the 2nd of June 1953, two climbers struck out for the summit of the unconquered Mount Everest on the 29th of May. A section of sponsored journalists who were part of the expedition was waiting at a high camp—21,000 feet—for news of success or failure. It was hours before the words broke out and the news was rushed down towards the base camp in the gathering darkness. There were human mail runners—a half-dozen trusted Sherpas who carried updates from the expedition 200 miles from Base Camp to Kathmandu. There had never been bigger news to deliver.

By the time Tenzing Norgay and Sir Edmund Hillary reached the summit of Mount Everest in May of 1953, the British had been trying to climb it for 31 years. This was the country’s ninth expedition, in addition to two reconnaissance flyovers commissioned by England’s wealthy elite in the 1930s. Meanwhile, several other countries had been trying to find their way to the summit at 29,035 feet, continually threatening to grab the prize away from the Crown. If the 1953 British expedition was unsuccessful, France had the permits in hand to try next. French legend Maurice Herzog had already scaled the Annapurna I, and the British were wary of this fighter waiting in the wings.

It was no overstatement how badly the British needed this. Over the previous decade, a years-long World War II bombing campaign—the Blitz—had destroyed over a million British homes, and the cost of victory put a damper on the economy that lasted for years. In the summer of 1947, British control over India came to an end, resulting in widespread violence and massive loss of life. A few years later, in early 1952, their wartime king, George VI, died suddenly, a few months after undergoing an operation for lung cancer. In short, England was taking some lumps, and the nation was looking for something to celebrate. The coronation of Queen Elizabeth II coincided nicely with Everest’s climbing season.

So, as the climbers descended, the race was on to tell the world. Sir Edmund Hillary and Sherpa guide Tenzing Norgay made the first official ascent in 1953 on the mountain’s southern side, in Nepal. The first Americans summited in 1963. The group included Barry Bishop, who wrote about and photographed the trip for National Geographic. Amid the Cold War, access to the mountain was severely restricted. China closed the Tibetan portion of Everest from 1950 to 1980. Nepal for years did not allow foreigners into the country to climb Everest in the 60s.

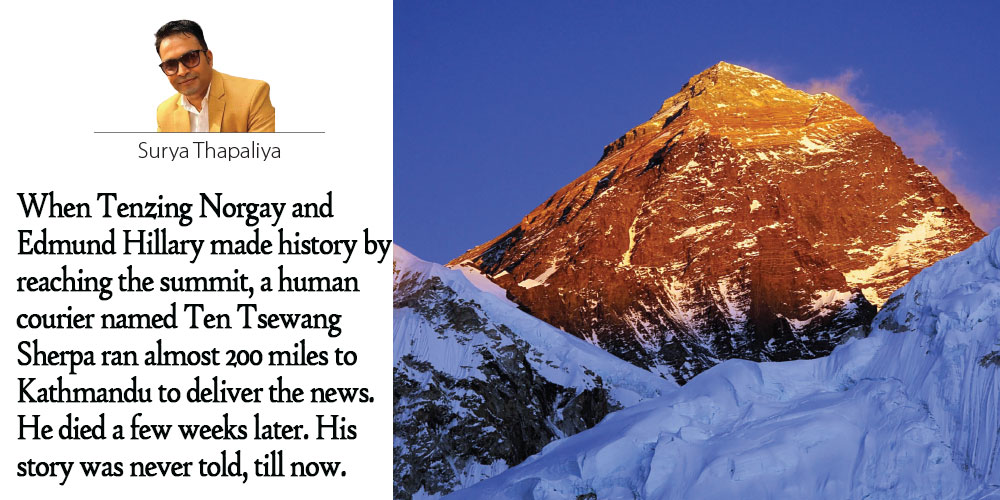

When Tenzing Norgay and Edmund Hillary made history by reaching the summit, a human courier named Ten Tsewang Sherpa ran almost 200 miles to Kathmandu to deliver the news. He died a few weeks later. His story was never told, till now.

Ten Tsewang was like a Nepali Pheidippides—the Greek messenger who famously collapsed and died immediately after a 26.2-mile run to tell ruling officials in Athens that they’d won the battle of Marathon. The Pheidippides story is probably still a mystery, but it became a powerful part of Western cultural history and pop culture. Ten Tsewang did something similar in real life, perishing a few weeks after delivering perhaps the last piece of world news ever sent by a runner. And his name, as far as history unfolded, had never been written down. His soul might wander the route even today. But then there is now the famed Everest Marathon, which starts at Base Camp every May 29 and follows the path the mail runners travelled to the village of Namche. The story is still fuzzy, but the legend of the human runner still lives in the mountains.

(Thapaliya is working as a manager at the Nepal Tourism Board and also holds a PhD in tourism studies.)

-original-thumb.jpg)