- Tuesday, 10 March 2026

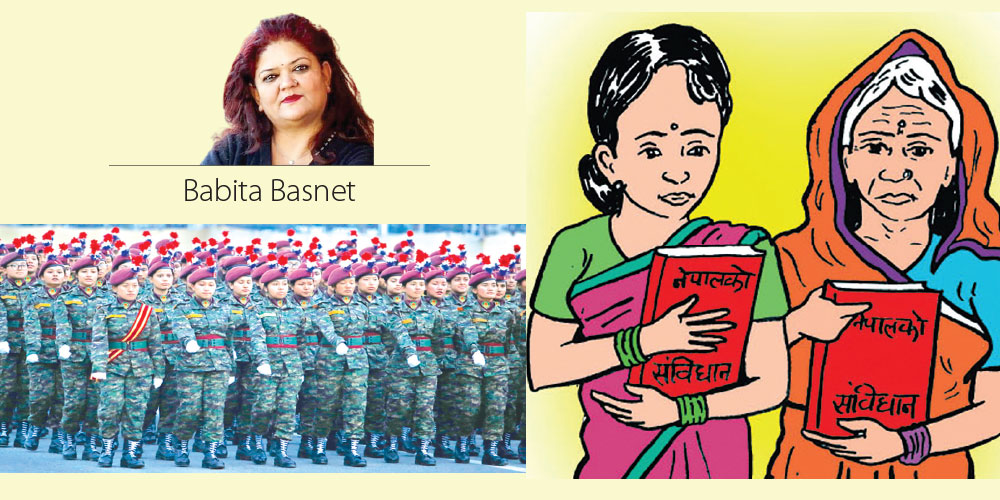

Secure Gains Made In Women Empowerment

“What has the Constitution of Nepal, 2015, given to Nepali women?” I asked Jhowa BK, a member of the Karnali Provincial Assembly, in October 2019. Her response was simple yet profound: "I was herding cows, buffaloes, and sheep at my village in Mugu. The constitution sought me out and made me a member of parliament."

This powerful answer came from a woman who never had the chance to attend school, yet her experience illustrates the transformative impact of the constitution, even in the most remote areas of the country. The Constitution of 2015 includes several provisions to ensure gender equality and social inclusion. It guarantees equality and prohibits discrimination based on gender, caste, ethnicity, religion, and other identities.

The constitution grants women the right to participate in all sectors of the state and ensures proportional inclusion in politics and government institutions. It also prohibits physical, mental, sexual, and other forms of violence against women.

Additionally, it guarantees 33 per cent reservation for women in federal and provincial parliaments, resulting in one-third of the seats in all seven provincial assemblies and the federal parliament going to them.

The constitution offers provisions for proportional representation for women, Dalits, Indigenous groups, Madhesi, Tharu, Muslim, and other marginalised communities in legislative elections to promote social inclusion. This was made possible by an inclusive electoral system, with intersectionality being a key feature of both the constitution and its electoral framework.

The provision of positive discrimination has created opportunities for women to participate across various sectors. Currently, women make up around 28 per cent of the civil service in various roles. Without this policy, it is unlikely that a woman would have ever held the position of Chief Secretary.

However, with this initiative, a woman has served as Chief Secretary, and the number of women in senior roles, including secretaries, continues to increase. Presently, women make up 11.78 per cent of police offers, 9.76 per cent of the Armed Police Force, and 9.4 per cent of the Nepali Army. This rise in female representation in the security sector is largely due to the positive discrimination policies introduced by the constitution.

Although women first joined the Nepali Army in 1961, their roles were limited to technical positions. It was only in 2005 that recruitment policies expanded, allowing broader participation. During the Maoist insurgency, the Maoists claimed that 40 per cent of their fighters were women, making it the only war in Nepal's history where women actively participated in combat.

Since the establishment of the Nepal Police in 1950, women have also made notable progress. The first policewoman, Constable Chaitmaya Dangol, joined in 1951 and retired after 32 years of service. Women's representation now spans from constable (Jawan) to the rank of Additional Inspector General of Police (AIGP). The establishment of the Armed Police Force during Nepal's conflict period further expanded women's roles, including responsibilities like border security.

The constitution also significantly advances the rights of minorities. It recognises the right of individuals to self-identify their gender and prohibits discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity, making Nepal one of the most progressive countries in South Asia regarding LGBTIQ rights. This aspect of the constitution is a crucial milestone in advancing equality and inclusion for all.

Gender inclusion at the local government level is another significant achievement of the constitution which mandates the inclusion of women and marginalised groups in governance. As a result, women make up 41 per cent of local government representatives, with 79 per cent of these women serving as deputy mayors or vice chairs. However, only 4 per cent of mayors and 3 per cent of rural municipality chairs are women, with women occupying just 1 per cent of ward chairperson roles.

The Local Elections Act mandates that either the mayor or deputy mayor must be a woman. However, there is growing debate about revising this provision to ensure that 33 per cent of ward chairpersons should be women. Additionally, there is a growing need to ensure the representation of the LGBTIQ community and people with disabilities in local governance.

Since the implementation of the 2015 Constitution, several gender-responsive policies and laws have been introduced. These policies cover areas including youth, cooperatives, non-formal education, health, drug-related policy, information technology, elections, civil service, right to information, the Nepali Army, land-related policy, local governance, and foreign employment. Additionally, specific laws, including the Human Trafficking and Control Act, the Domestic Violence Act, and both the Civil and Criminal Codes, have been enacted. These laws have the provisions of penalties related to rape, marital rape, acid attack, discrimination, child marriage, and humiliating behaviour.

While this legal framework is strong, the emphasis now needs to shift from creating new laws to effectively implementing the existing ones. In Nepal, the challenges are often poor enforcement, particularly for laws related to women's rights, such as those addressing domestic violence and property rights. One law that remains largely unenforced is women's right to parental property, despite the legislation guaranteeing equal rights.

As discussions on amending the constitution continue in Nepal, there is a concern about whether women's rights will be protected if changes are made. Of particular concern is the political participation of women. Without strong constitutional provisions, there is a risk of losing hard-won achievements and regressing to previous conditions. How to ensure women's participation and institutionalise the progress made so far should be central to any debate on constitutional amendments.

(Basnet is an executive director at Media Advocacy Group.)