- Monday, 2 March 2026

Talking To Kathmandu Sympathetically

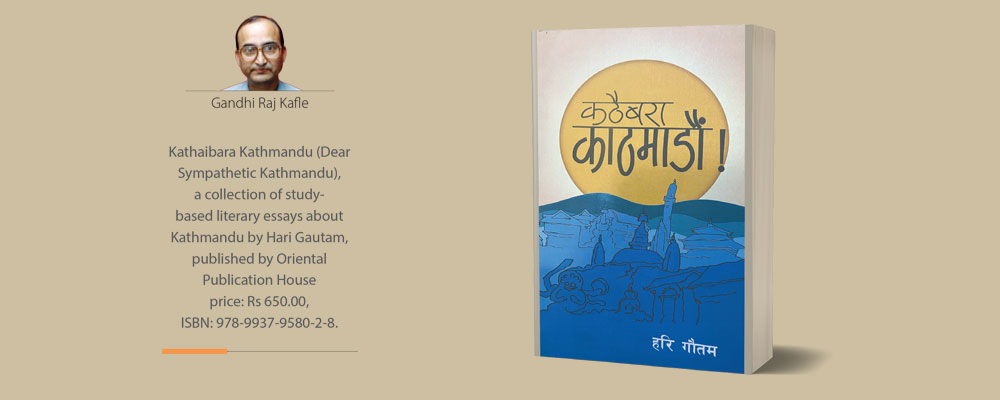

Genuine sympathy is the power of good wishes, and languages all over the world have their own particular words to communicate the right meaning of this connotation to speakers. Here in Nepali, Kathaibara is that word. But the question in the context of the under-review facts-laden 368-page book entitled Kathaibara Kathmandu by Hari Gautam is: Does Kathmandu, which keeps all powers to govern the country, need any such sympathy? The common understanding of the people with this curiosity is that it is not Kathmandu but the other less developed parts of the country that require Kathmandu’s sympathy for development and care.

Then, the question arises for author Gautam to furnish justification because he has addressed the country’s capital city of Kathmandu with the sobriquet Kathaibara. Indeed, the reasons and proofs are there in this book, but many of the justifications furnished by the author are related to the sentiments and love of the people of Nepal as well. Maybe, by loving this way of saying it, Prof. Hem Chandra Nepal has called Hariji the master jeweller of words in the preface of this book.

There is no big point in doing research and writing for the author. What Gautam has experienced is also felt by many: How can many senior citizens from outside this beautiful valley forget the words ‘Nepal Jaane’ (going Kathmandu) when the city had no modern transport facilities and foot travel was only the means to come? The researcher’s writing curiosity starts right here.

One relevant quote is on page 12, where author Orhan Pamuk’s words, ‘The man who is not happy with his city can’t be happy with his own life’, have been mentioned. The other argument mentioned by the author is by historian Huta Ram Baidhya, who criticises the building of public toilets on the riverbank of holy Bagmati after receiving a loan from the Asian Development Bank (ADB). This means we are forgetting our own cultures and civilizations and copying blandly the modern method of construction for city amenities. Therefore, Pamuk and Baidhya’s quotes are like warnings to Kathaibara Kathmandu.

This freshly published book has two parts. In Part 1, there are thirteen essays. The first essay is Kathaibara Kathmandu, which is also the book's title. The last essay entitled ‘Nepal-Bharat Cultural Relations’ in this part is related to Nepal’s fundamental values of bilateral ties with its southern neighbour, India.

It seems the first part of the essay, as the titles of the authors suggest, is related to the changing socio-cultural and economic circumstances of Nepal as a whole. The Valley of Kathmandu is in deep focus, but the nation’s suffocations and aspirations have also been dealt with beautifully in this study.

But some themes and words are also important from the point of view of psychology and meta-physics, even in the first part of the essays in the book. We can mention these themes here: times and awareness, times and society, midnight dreams, the necessity of life, marriage, etc. Hariji has studiously argued such points, and he has broadened the subject matter to new heights in each essay. He is dreamy, both in content and in writing.

However, the second part, where we find six essays, is thematically different because it discusses man’s intrinsic existence, and so it can only be felt. The experiences described by the author only help readers enter the depths of grave themes. Let’s mention essays in this part. The titles here are ‘Death Feelings’, ‘Mother is No More’, ‘Suffocations Befell from Landslides’, ‘Decorated Memory of That Damak’, ‘Unforgettable Travel', and ‘Survived This Way by A Phone Call’.

No doubt, life sometimes reaches a nadir. But is it the end? If it is not so, who comes there for rescue? Rising from such situations always baffles human beings. Author Hari Gautam has made a scholarly and deep exercise on the mystic aspect of this theme for writing “Kathaibara Kathmandu.”.

Our dear Kathmandu, the Nepali society and civilization at a broader level, or we as an individual entity who need support from Kathmandu at a small level, are all sentimentally interlinked. So, we have the right to ask questions about Kathmandu, especially on themes related to national good governance.

Finally, coming to this book, author Hari Gautam has loved to discuss the national capital of Nepal with multidisciplinary norms. So, the word's sorry, Kathamandu’ or ‘Kathaibara’ need to be taken sympathetically and compassionately. No doubt, the Nepali people have suffocations about their capital, but history is proof our capital, too, has its suffocations.

Author Gautam’s multidisciplinary approach has brought this issue to the limelight.

The author deserves kudos for delivering this research-based literary stuff to Nepali readers.

(Kafle is a former Deputy Executive Editor of this daily.)