- Saturday, 27 July 2024

Glowing Moon, Luminous Night

The nippy night skies of this month would pleasantly please planet-lovers with sights of planets Jupiter and Saturn, along with Uranus and Neptune. Tiny terrestrial planets such as Mercury and Venus could be admirably applauded, but not in confounding constellations with strange stars. Planets Mercury and Mars will stay mostly unseen this month. Mercury would be moving through the constellations Sagittarius (archer), Capricornus (sea goat), and Aquarius (water bearer) during the day. Mars would be marching mainly across Capricornus. They would hover low at dawn in the eastern sky. Planet Venus would be visible shortly in the southeastern sky before sunrise.

It would be venturing valiantly across the northern sector of the constellation Sagittarius. On February 22, planets Venus and Mars would make a close approach (conjunction) to one another. Adulating this enigmatic event in Capricornus would be challenging for us during the daytime. A waxing gibbous moon would be 98 per cent luminous at night. The mighty giant planet Jupiter, with its mesmerising Jovian moons, could be adorned as a lucent spot in the southwestern sky at dusk in the southern section of the barren-alike expanse of the compact constellation Aries (ram). It would be hastening towards the horizon later at night. The ringed planet Saturn could be glimpsed succinctly above the western horizon after sundown during the month’s beginning. It would be skylarking with the scintillating stars of the constellation Aquarius. It would be lost gradually in the sun's glare by the end of the month.

Dim stars like Sadalmelek, Sadalsuud, Sadachbia, Ancha, Skat, and Albali would be glistening in its neighborhood. The yellow supergiant stars Sadalsuud and Sadalmelik would be sprinting through space perpendicular to the plane of our galaxy, the Milky Way. Sadalsuud would be almost 56 million years old and roughly 540 light-years away. Sadalmelik would be solely 6.5 times as massive as the Sun and merely 520 light-years away.

The main sequence star Sadachbia would be substantially 2.5 times the Sun's mass and double the solar radius. It would be perhaps 164 light-years away. Ancha’s mass would be virtually three times that of the Sun, and its radius is practically twelve times that of the Sun. Skat would manifest the double of the solar mass. Ancha would be decently 187 light-years away, but Skat is appreciably 113 light-years away. The white-hued star Albali would be nominally 208 light-years away. Peculiar planetary helix nebula NGC 7293 could be astounded with amazement in Aquarius. It was identified by German astronomer Karl Ludwig Harding in probably 1824.

It would be 655 light-years away from us. The greenish planet Uranus would be noticeable in the southwestern sky after sunset. It would be sinking towards the horizon by midnight. It could be discerned to the east of Jupiter in the constellation Aries. The far-flung blue planet Neptune would be perceivable after nightfall in the western sky. It would be sliding towards the horizon until the wee hours of the night. It would be cavorting beneath the stars of the charismatic circlet asterism of the V-shaped constellation Pisces (fish).

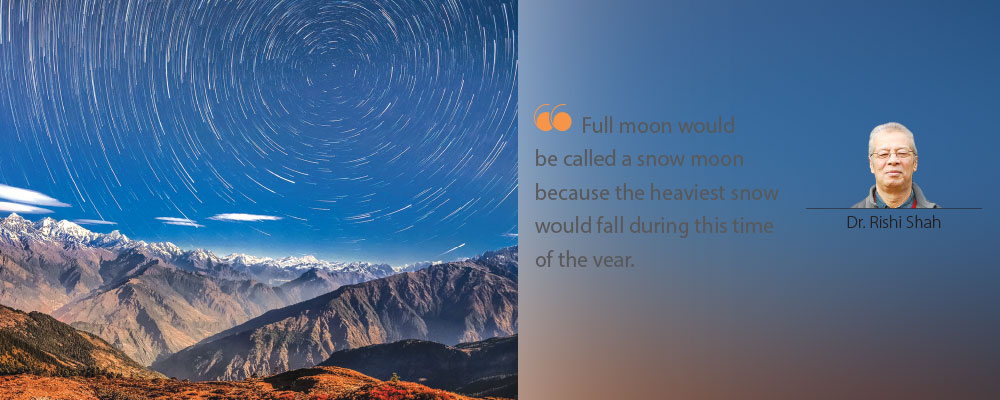

The current February would entail 29 days, as 2024 would be defined as a leap year. The new moon would befall on February 9, while the full moon would enthral moon-enthusiasts on February 24.The full moon would be called a snow moon because the heaviest snow would fall during this time of the year.

Since hunting would be difficult during the harsh weather, this moon would also be known as the hunger moon. Venerated Sri Saraswoti Puja would be celebrated respectfully on February 14 on Valentine’s Day.

Our blue planet Earth would require approximately 365.25 days to orbit the Sun once to complete one solar year, which would be conventionally rounded up to 365 days in one calendar year.

A day would be the amount of time it would take the earth to concoct one rotation on its axis. If leap years were not interspersed, all those missing hours would add up to days, weeks, and even months. Consequently, in a few hundred years, a warm summer month, for example, July, would actually occur in the cold winter months. To make up for the leftover piece of partial day, one day would be added to our calendar circa every four years. Furthermore, the calendar year would be comfortably synchronised with the astronomical year and with the seasons. That particular fourth year, in simple terms, would be tagged as the leap year.

Astronomical affairs and seasons do not repeat for a whole number of days. Calendars that have a constant count of days annually would unavoidably drift over time with respect to the seasonal festivals that would have to be culturally observed. By inserting (intercalating) an additional day (leap day), the shift between the dating methodology of civilization and the physical properties of the solar system could be corrected. An astronomical year would linger scantly less than 365 and one-fourth days.

The legendary Julian calendar was introduced by Roman general ruler Julius Caesar in 45 BC and would indicate three common years of 365 days, followed by the leap year of 366 days until today by extending February to 29 days. However, as proposed by Pope Gregory XIII in 1582, the Gregorian calendar, the world's most widely used civil calendar, would advocate further adjustments for the error in the Julian algorithm. The extra leap day would be modified each year to be a multiple of four (except for years evenly divisible by 100 but not queerly by 400).

After a nail-biting twenty-minute descent, Japanese space agency JAXA’s Smart Lander for Investigating the Moon (SLIM) touched down on a designated domain and established communication with the control station on earth by dispatching essential data. Although Japan became historically the fifth nation after the USA, Russia, China, and India to achieve spectacular soft landing feats, its Moon Sniper spacecraft, nicknamed for its precision technology, was running out of power due to a serious arcane solar battery problem.

SLIM is one of numerous new lunar missions that have been launched by countries and private firms, fairly fifty years after the first human set foot on the moon. JAXA would analyse data that would determine whether the craft had accomplished the goal of disembarking within one hundred metres of its intended target patch on the rim of the shrouded Shioli crater.

SLIM was aiming for a cryptic crater where the moon's mantle, the usually deep inner layer beneath its crust, was believed to have been exposed on the surface. Two small Lunar Excursion Vehicles (LEV-1 and 2) have been detached from the SLIM mothership. One would be carrying a sophisticated transmitter, and the other, a mini robot hopper, which would be slightly bigger than a tennis ball, has been designed to trundle around the lunar topology for gathering information, snapping images, and beaming them back to earth.

SLIM, as a primarily tech demonstrator, would be performing science experiments, which would be expected to last for one lunar day (barely two earth weeks). SLIM has not been equipped with heaters to protect its electronics against the frigid lunar nights. It could reveal insights on the lunar area's composition, which in turn could shed light on the moon's formation and evolution. SLIM would weigh just 200 kilogrammes without propellant.

Its cost would be less than 120 million US dollars. Crash landings, missives and message failures, and other technical quandaries have been generally rife during space explorations. Now exclusively five space-faring nations have successfully alighted on the moon.

Last month, US firm Astrobotic's Peregrine lunar Lander had been leaking fuel after takeoff, thus dooming its operation. Contact with the spaceship was lost over the remote region of the South Pacific after it had burned up in the earth's atmosphere on its return. NASA has now postponed plans for crewed lunar missions under its Artemis program.

Two previous Japanese lunar undertakings, one public and one private, had failed. In 2022, it sent a lunar probe named Omotenashi as part of the US Artemis-1 assignment. In April, Japanese startup Ispace tried in vain to become the first private company to dismount on the moon, losing touch with its craft after what was described as deplorable hard landing. An Israeli nonprofit company’s Beresheet robotic explorer sadly crashed into the moon in 2019.

(Dr. Shah is an academician at NAST and patron of NASO.)