- Monday, 16 February 2026

Transformative Funding For Education

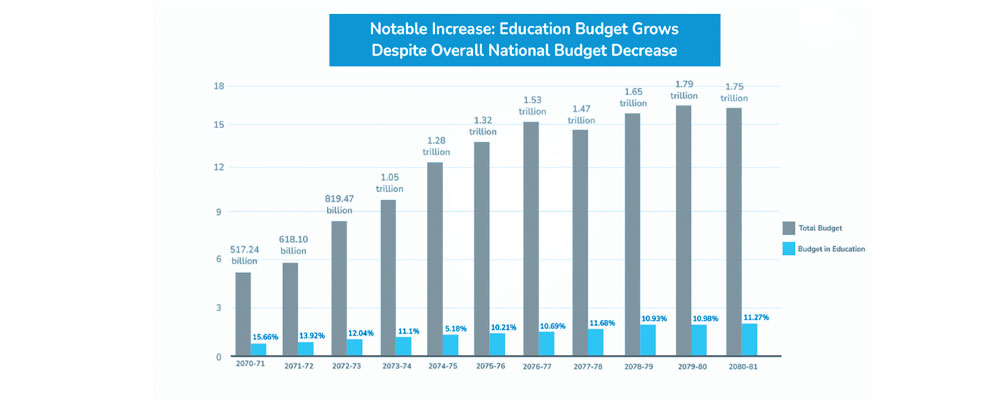

In Nepal, education discourse often revolves around the inadequacy of budgets. The conventional financing approach has raised concerns regarding insufficient funds for education. The government of Nepal spends about 11 per cent of the total budget on education. The amount is insufficient for free and compulsory quality education, as we assumed in the constitution. Stakeholders are demanding at least 20 per cent budget allocation in education. However, it's time to explore new approaches to education financing, as global practices suggest, which can be best for countries like ours with low financing. Innovative investment in education is becoming a prominent approach in developed nations like Finland, Denmark, and Norway, which have strong education systems. To drive positive changes in education in Nepal, innovative financing models are crucial.

There are several challenges associated with the traditional method. Traditional budget allocations, based on historical trends, may not keep up with these evolving needs, leading to insufficient funding for education. In traditional systems, almost 80 per cent of the allocated funds are used for administrative and operational expenses, leaving a smaller portion for direct educational activities. This inefficiency can hinder the improvement of educational infrastructure and resources. Likewise, traditional budget allocation models often lack flexibility and creativity. They may not encourage innovative approaches or adapt to changing educational requirements. And it also resulted in disparities in educational access and quality. In Nepal, the government allocates about 11 per cent of the total budget, where most of the budget is spent for administrative work, and as a result, the budget is not sufficient for academic work. Therefore, private sector involvement in education is also found in Nepal. Likewise, private financing plays a role in the education sector in Nepal. But it can also result in disparities in access to quality education. Nepal faces several challenges in education financing, including insufficient funding, inequality, quality improvement, and administrative efficiency.

A case study

Even some local governments in Nepal are taking extra initiatives. Suryadaya Municipality in Ilam, Nepal, has taken significant initiatives in the education sector, with a focus on enhancing access to quality education and connecting local agriculture with pedagogy.

The municipality introduced an impressive educational tool called the Interactive Panel Board.The Board enables students from multiple schools to join live math and science classes delivered by teachers from Phikkal Secondary School and Jyoti Secondary School. This innovative approach can help overcome geographical barriers and improve access to specialised interactive education, which also tackles the deficit and shortage of teachers. Rana Bahadur Rai, head of the municipality, said now students are not compelled to stay in leisure classes even if the schools don't have particular subject teachers.

The Innovation Centre is another impressive project. It has established an innovation centre with the primary goal of making the region an agricultural hub. Given the importance of agriculture in many rural areas, this initiative can lead to increased agricultural productivity and economic development. The centre can serve as a hub for research, training, and the dissemination of best practices in agriculture.

It's noteworthy that 65 per cent of students in Suryadaya Municipality are studying at community schools. These schools play a crucial role in rural areas, and focusing on improving the quality of education in community schools can contribute to equitable access to education for a majority of the students.

The municipality is unaware of innovative financing models, but these initiatives reflect a commitment to education, innovation, and agricultural development in the municipality.

Concept

Innovative financing in education offers a solution to these challenges by introducing fresh and creative approaches to funding education. Innovative finance includes mechanisms and solutions that increase the volume, efficiency, and effectiveness of financial flows. There is no universal model for innovative financing; instead, authorities in each specific location can develop and implement a financing model that aligns with local needs and circumstances.

But innovative financing in education entails thinking creatively and unconventionally about how to raise and allocate funds to improve educational outcomes, access, and quality. These approaches aim to address the challenges and funding gaps that may exist in traditional education financing models. Innovative financing seeks to support educational initiatives and reforms, particularly in situations where government budgets alone may fall short of meeting the demands of a growing and evolving education system.

Innovative financing in education encompasses various creative methods, like receiving extra tax from areas like tourism, airlines, hotels, and others. Likewise, providing digital devices, internet access, and educational content to students, especially in remote areas, can minimise the budget expenditure as well as fulfil teachers' requirements, and collaboration between governments and private sector entities to fund and operate educational facilities, such as schools, universities, and vocational training centres, can benefit from philanthropic support.

Besides that, government-issued vouchers are also popular globally now, where the government gives a check or voucher to students while parents search for the best schools for them.

Creative financing approaches foster innovation both in funding models and in the development of new educational solutions. They encourage experimentation and creative thinking to find more effective and efficient ways to address educational challenges.

Innovative financing can promote greater equity in education by targeting resources where they are needed the most. For low-income countries facing budget constraints, innovative financing opens the door to a wider pool of capital sources.

And innovative financing models tie financial incentives to achieving specific educational outcomes. This ensures accountability and a results-driven approach, where investors or funders are rewarded based on the actual impact of the programmes they support.

As the municipality is doing its best out of its own model, educationalist Dr. Baburam Adhikari also suggested developing one's own model of innovative financing rather than copying from international practices. "We have to set the indicators of innovative financing according to our context rather than copying from others. Only self-motivated indications can be implemented successfully; therefore, we have to develop the indicators by keeping three-layer governments at the centre.

Dr. Bal Chandra Luitel, another educationist, suggests strengthening the public financing model that we are adopting now. This involves increasing investments in the education sector and optimising the allocation of resources to ensure that schools receive the necessary funds to improve both the quality and accessibility of education. "We have to explore additional revenue sources to strengthen public financing. One proposal is to consider implementing extra taxation in certain areas, such as the tourism and airline sectors. These targeted taxes can serve as dedicated sources of revenue specifically earmarked for the education sector, potentially providing the necessary financial boost to enhance educational facilities and resources.

Likewise, he suggested utilising technology for content development. Harnessing digital tools and resources can revolutionise how educational content is created and delivered. Another critical aspect that Dr. Luitel stresses is the importance of effective budget management. He suggests that the existing budget can be sufficient for addressing educational needs if it is managed efficiently and transparently. Proper budget management ensures that the available resources are used optimally, allowing for a greater impact in the education sector.

Lastly, Dr. Luitel recommends looking up to developed nations as examples. Many developed countries have a history of substantial and consistent investments in education, even during their development phases. Studying their approaches and best practices can provide valuable insights and guidance for Nepal as it seeks to strengthen its education system.

Dr. Pramod Bhatta, another educationist, advocates for the decentralisation of education in Nepal. He emphasises that local governments should play a more significant role in monitoring and overseeing the education system. This approach can increase transparency and accountability within the system, as local authorities are better positioned to understand and address the specific needs and challenges of their communities.

The arrangement of "Ghumti Teachers" who move from school to school may minimise the budget expenditure. The provision can be effective mainly in remote areas that have been facing teacher shortages most of the time.

Furthermore, Dr. Bhatta recommends implementing targeted programmes like 'Padhdai Kamaudai', earning together with learning. Such initiatives can help identify and support children who are out of school or at risk of dropping out. By providing tailored support to these students, Nepal can work towards a more inclusive and equitable education system. Dr. Bhatta also emphasises the importance of utilising technology in education management and delivery. This can include digital tools for administrative tasks as well as online or remote learning to reach students in remote areas and promote flexibility in education delivery.

Lastly, Dr. Bhatta suggests exploring the voucher system, where students receive educational vouchers that can be used in various schools. This approach can widen school choice and promote healthy competition among educational institutions, potentially leading to improved quality and innovation within the education sector. He said implementing these new models according to the needs of local levels can be taken as one's own model of innovative financing.

These expert suggestions encompass a wide range of strategies to enhance the education system in Nepal, including financing, governance, technology integration, and targeted programmes. The implementation of these approaches, in combination, holds the potential to significantly improve the quality and accessibility of education in the country.

International practice

A number of developed nations have adopted innovative financing models with great success. These models have led to improved access to quality education, enhanced infrastructure, and better educational outcomes. By embracing these global practices, countries like Nepal can learn from the experiences of others and adapt similar models to their specific contexts.

For example, the UK has been practicing financing models like education venture funds, debt conversion development bonds, diaspora bonds, and travel savings funds for development.

In Denmark, public support for students is excellent. The two main institutes responsible for dealing with student support are the agency and the ministry. The agency deals with student applications, communicates with educational institutions, pays out grants and loans, and writes budgets. The Ministry does the general planning and budgeting and is also in charge of any amendments to the system. Foreign students (unless under special status) are not able to use educational assistance. Of those able to use support, about 50 per cent take advantage of the loaning system.

Likewise, Norway's education system is mainly funded by public expenditure, with very little private funding. Public primary and secondary schools are free of charge. Only 3.3 percent of children in Norway attend private primary and lower secondary schools, and most private schools receive some state funding.

There are different practices around the world in terms of how government money is spent on education. One such practice is the voucher system.

Voucher system

According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), 88 countries worldwide (25 out of 34 OECD members) have some form of voucher system in place. This system is also known as the School Choice Programme, as it allows students (parents) to choose their school.

Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Hong Kong, Hungary, Iceland, and Ireland are the countries that partially or fully embrace the voucher system. India, Japan, Korea, Luxembourg, Mexico, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, the UK, and the USA can also be placed on this list.

Implementation of the school voucher system in these countries is not uniform. Some offer vouchers to attend a private school of the student's choice, while others allow vouchers to be used only by religious schools or schools that serve minority, disadvantaged, or low-income students.

Voucher systems not only reduce the burden on the government to provide education but can also increase the efficiency and accountability of educational institutions. Children can go to the school of their choice.

Efficient use of resources can reduce the cost of public education and increase teacher and student attendance at school. Most importantly, competition creates pressure for public schools to improve.

The government of Nepal spends about 11 per cent of the total budget on education. The global average is 17 per cent. Although lower than this, it is higher than the South Asian average (9 per cent). Looking at the budget for the last few years, it seems that the government of Nepal spends an average of 18,000 rupees annually on each student studying in public schools. It also provides separate scholarships and financial assistance for the poor and other identity groups.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the status of education financing in Nepal faces significant challenges, including insufficient funding, inequity, and administrative inefficiency. Experts have suggested and showcased innovative financing models through local initiatives to address these issues and bridge budget gaps. These models encompass strategies such as targeted taxation, technology integration, improved budget management, decentralisation, and voucher systems. Learning from global practices, countries like Nepal can adapt successful models to their unique contexts, as demonstrated in other countries. These innovative approaches hold the potential to improve the quality and accessibility of education, ensuring a better future for the youth of Nepal.

(Dhakal is a journalist at The Rising Nepal)