- Saturday, 27 December 2025

Meditation Therapy For Cancer Treatment

Dr. Ainslie Meares, founding father of Stillness Meditation Therapy, was born in Melbourne in 1910. After graduating in medicine from Melbourne University, he spent some time working at an army hospital, treating soldiers who had been mentally disturbed by their war experiences. It was this exposure to the suffering caused by anxiety and the insightful link he made between anxiety and its relationship to physical illness that led him to dedicate his life’s work to the field of psychiatry.

After the Second World War, Dr. Meares continued practicing psychiatry but became disenchanted with treatments such as psychoanalysis, electric shock, and drug therapy. His expertise in clinical hypnosis brought success, but within this aspect of his work, Dr. Meares discovered that some patients recovered without deep-seated problems being resolved. He began to identify the reason for this as a different state of mental function, which resulted in healing.

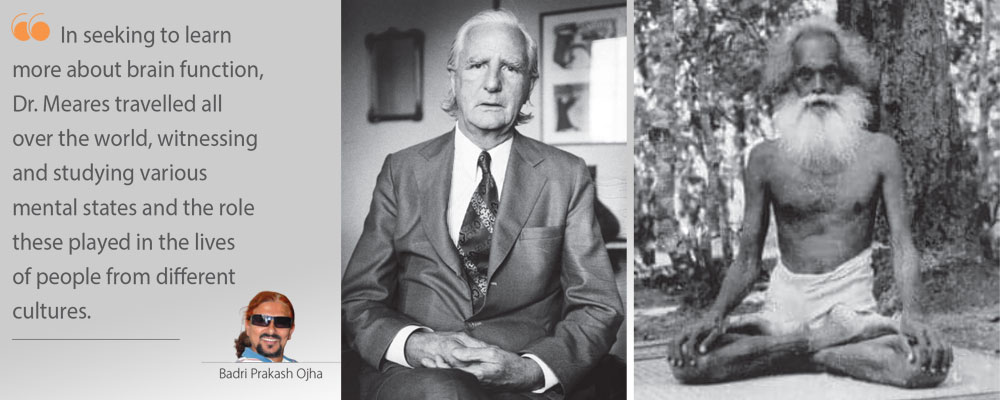

In seeking to learn more about brain function, Dr. Meares travelled all over the world, witnessing and studying various mental states and the role these played in the lives of people from different cultures. It was during one such visit to Kathmandu that he was introduced to meditation by Shiva Puri Baba, a revered yogi, in his Ashrama in Dhruvasthali. As per British Government records, the Baba used to teach yoga to queen Victoria in England. Baba’s remarkable life spanned an astounding 137 years from 1826 to 1963. The fact that he walked every continent except Antarctica on his world pilgrimage, beginning at around 60 years of age, lasted over 30 years. Baba met many of the great men and women of the early twentieth century, such as Einstein, the Curies, Marconi, Tolstoy, etc. Baba had eighteen audiences with queen Victoria but about all that, he wanted nothing said, no publicity at all.

Dr. Meares met this widely respected Baba in the early 1960s. The venerable sage gave Dr. Meares a perspective on pain that literally changed his personal and professional life. Responding to questions about how he managed pain, the Baba quite simply stated, “I experience pain, but it does not hurt.” Pain without hurt! How could this be? And could it be taught as a genuine and practical way of alleviating pain? Again, when asked, the sage had a simple answer: “To experience the truth of this, you must learn to meditate.”

After staying with Baba for three days, Dr. Meares returned to Melbourne to begin experimenting with himself as a guinea pig. During his experiment, Dr. Meares was able to have his own major dental surgery performed using a sharp blade, chisels, and hammers but no anaesthetic, and surprisingly, he felt no pain. He was convinced that he was on to something of major medical significance.

Quickly moving on to the realm of pain management, Dr. Meares realised that to meditate was to enter into a state of deep physiological rest. He developed a reliable way to relax physically, to calm the mind, and to flow on into a consciously aware state beyond thoughts: deeply relaxed, deeply at peace, essentially still, motionless in body and mind.

A specific form of meditation based on stillness, what Dr. Meares reasoned was that in this deeply relaxed, calm stillness, the body regressed to a state of inner balance that established and maintained good physical health. He realised that there was more on offer than just the obvious physical benefits. The type of meditation that he developed flowed on to provide balance in emotion, mind, and even spirit.

Dr. Meares’ first book on meditation, Relief Without Drugs, was groundbreaking. Published in 1967, it circulated around the world to popular acclaim.

But his colleagues were nonplussed. Often misunderstood in those early days, sometimes even derided, Dr. Meares decided to deregister himself as a medical practitioner so that he could convert his psychiatric practice to a meditation-based practice and the ramifications from the Medical Board.

Dr. Meares was a genuine pioneer in the therapeutic application of meditation. He was probably the first major medical identity to work seriously and consistently with meditation. In all, he published 32 books, many on the theme of meditation, and 23 articles in major medical journals specifically examining the links between the mind, meditation, and cancer.

In 1975, Dr. Meares confidently announced to the medical world that he believed intensive meditation may in fact reverse cancer. At that time, many in the medical world condemned him for what they believed to be an outrageous claim.

Dr. Mesears met Ian James Gawler, a young cancer patient. Gawler had bone cancer, which was widely spread throughout his body. Back in the 1970s, all the medical texts said that this aggressive cancer was fast-moving and uniformly fatal once it had reached the stage he was in. Medically, he could be expected to live for three to six months, and modern medicine at that time had nothing but pain relief to offer him.

"On the first meeting with Dr. Meares, I was struck by his hypnotic presence. He spoke slowly and quietly. In a measured tone, he explained how, based upon his experience as a psychiatrist, he felt that the chronic stress that cancer patients tend to bottle up inside of them leads to significant physiological changes in the body," wrote Gawler in his memoir.

Dr. Meares postulated that this alters the levels of an array of hormones circulating in the body, especially cortisol, a hormone that causes stress and lowers the immune system in the body.

This in turn affects the body’s immune system and its capacity to resist or eliminate small cancers when they form, thus allowing them to develop into clinical disease.

"When we meditate, he told me, our body relaxes, and the mind goes with it. As we become calmer, the calm flows into our daily lives. More calm. Less stress. Cortisol levels go down. Our body's defences go up. Our body is what does the healing," says Gawler.

It made perfect sense to him—intense meditation. Perhaps this is the chance to heal. Certainly the chance to explore his interest in meditation itself. By intense, Dr. Meares meant three hours of meditation a day. So over the next six weeks, Gawler met with him regularly to learn and practice his style of meditation. Soon, Gawler made time to work five hours a day. He had no time to lose, as he was to leave his body within months.

Three months later, the cancer had not grown at all. This in itself seemed like a miracle. Then pain became an increasingly major and debilitating issue. Gawler did not have the skills at the time or the capacity to manage it.

"What helped me the most, in my view, was what can best be described as the lifestyle activities that I developed and maintained—food, exercise, healthy emotions, and meditation, along with the support of my first wife," says Gawler.

In February 1976, Gawler had some palliative radiotherapy; in October 1976, he underwent three cycles of experimental chemotherapy. He was declared free of cancer in 1978.

Dr. Meares recorded this case in the Medical Journal of Australia in 1978. The media got hold of Gawler's story, and soon people from all over the world were seeking help with illness.

In 1981, after three years of answering countless letters and telephone inquiries and even having people turn up at his veterinary practice seeking cancer advice, Gawler decided to really test the proposition that what had helped him might also help others. He immediately started teaching Dr. Meares’ theories on meditation to large groups of people.

These groups turned out to be the first of their kind in Australia and among some of the very first in the world. The demand for them steadily grew, and a not-for-profit organisation developed to support the work, the Gawler Foundation. Currently, the foundation employs around 50 staff and conducts residential and non-residential programmes for people affected by cancer or multiple sclerosis, as well as wellness programmes and numerous meditation retreats. After recovering from cancer, Gawler resumed work as a vet professional for short periods of time. In 1980, he resigned the job and then moved to a new practice at Yarra Junction, Victoria.

In 1981, Gawler co-founded the Melbourne Cancer Support Group, a lifestyle-based self-help programme for people with cancer. The 12-week programme was based on Gawler's beliefs about his own recovery. Participants were taught dietary principles, relaxation, meditation, imagery, and pain management skills. Other sessions included techniques to develop emotional health, the power of the mind, philosophy, and the capacity to come to terms with and integrate the possibility of dying through cancer.

The programme was documented in Gawler's first self-help book, You Can Conquer Cancer. In 1995, the Gawler Foundation published Inspiring People, a collection of the personal experiences of cancer written by 50 people who had survived against the odds. In 2008, another collection, Surviving Cancer, was written by 28 people who had survived cancer and had attended the Gawler Foundation's programmes. It was launched by Chris O'Brien, former director of the Sydney Cancer Centre, based at the Royal Prince Alfred Hospital.

In December 2011, in Internal Medicine Journal, the online journal of the Royal Australian College of Physicians, two oncologists, Ian Haines from Cabrini Hospital and Ray Lowenthal from Hobart, published a report that no biopsy of Gawler for secondary cancer had been made and suggested that all of his symptoms were consistent with tuberculosis. In response to this report, Gawler maintained that the diagnosis was confirmed by his eminent team of physicians of the day and said that they still stood by that diagnosis. He said that Haines and Lowenthal did not consult with any of these people in preparing their speculative hypothesis and, therefore, did not take account of his clinical history or the many diagnostic tests performed and deemed to be adequate by those physicians to confirm the diagnosis. Gawler's original physicians maintained that the TB developed as a complication of Gawler's primary cancer, probably after chemotherapy weakened his immune system.

Lowenthal, who has long been a critic of Gawler's work, engaged in an hour-long debate on the ABC-TV show Couchman in 2012. He challenged Gawler to produce 50 of his best cancer recovery cases for review. Gawler agreed on air and welcomed "the opportunity for some serious research." The review has not happened, despite the fact that the 50 cases were made available by the Gawler Foundation at the time. Lowenthal was reportedly unable to receive funding for the study.

Gawler worked at the Gawler Foundation as therapeutic director until 2009. He still contributes to some programmes on a part-time basis. Gawler has been a keynote speaker at many conferences, including the Royal College of General Practitioners' "Happiness and its Causes" international conference. In 2010, he received the Winsome Constance Kindness Medal for his contribution to animal welfare.

(Ojha, a PhD in communication, is a meditation teacher.)

-square-thumb.jpg)