- Tuesday, 3 March 2026

Dealing with monkey menace challenging

Kathmandu, Sept. 7: Sarita Sharma, from Syangja, wrapped up her paddy planting last month and has been savouring a well-deserved month-long break following the completion of corn harvesting and paddy plantation.

For three challenging months, from April to June, she struggled to get a good night’s sleep due to the constant fear of monkeys, which posed a persistent threat to her precious corn crop, making it difficult to protect her harvest.

When the corn was in its early stages, she constantly worried that monkeys would uproot the plants. As the corn matured and was on the verge of bearing grains, her fear shifted to the monkeys potentially consuming her hard-earned harvest.

“Now that I have finally enjoyed a month of peaceful sleep, I know that when the paddy starts bearing grain, we will need to remain vigilant once more, as those mischievous monkeys might attempt to throw away all our precious paddy grains,” Sharma said.

While this is just one example, the issue of monkey-related problems extends to various districts including Dhankuta, Makwanpur, Kaski, Dolakha, Dhading, Gorakha, Arghakhanchi, Syangja, Tanahun, Baglung, Palpa, and many more. Farmers in these regions have turned to scarecrows as a solution to deter monkeys.

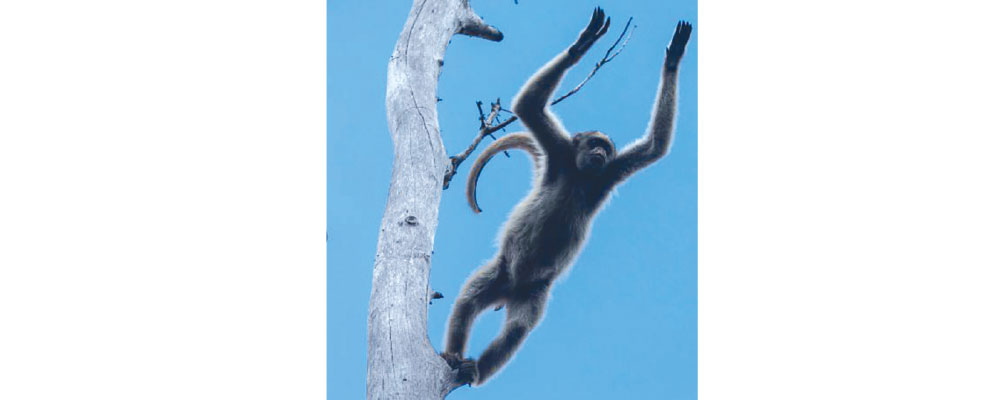

They are versatile creatures, residing in the jungles of the Tarai, the remote mountain areas, and even temple precincts. These monkeys are omnivores, consuming everything from insects to fruits, leaves, buds, and grains.

During the last election, a majority of the candidates incorporated promises of addressing the monkey problem into their campaign appeals, seeking support from the voters based on this issue.

However, Lekhnath Pokharel, the representative of the Rural Municipality Association, noted that despite these campaign promises, effectively controlling the monkey problem has proven to be an elusive challenge.

He has brought attention to the extensive monkey problem that has impacted the entire country, encompassing a total of 293 municipalities. Efforts aimed at controlling monkey populations have been unsuccessful, and currently, there appears to be no viable alternative to effectively manage this issue.

Pokhrel expressed, “Local authorities’ endeavours to control monkey populations have faced consistent challenges, and it now appears that coexistence with monkeys is a necessity, as there is no practical solution for their elimination.”

Dr. Sabina Koirala, the monkey expert, highlights that conflicts between monkeys and humans intensify when both share the same habitat. During her PhD research in monkeys, she observed various reasons behind the increasing human-monkey conflicts in the rural areas. She emphasises that these conflicts are most prevalent in the mid-hill regions of Nepal, where such clashes are more pronounced than anywhere else.

Dr. Koirala emphasised that resorting to lethal measures is not a viable solution, given the strong familial bonds among monkeys. Instead, she advocated for a decisive and effective strategy to manage the monkey population.

Nepal is home to three species of monkeys, which are the Hanuman Langur, Rhesus Monkey, and Assamese Monkey. Among these species, Assamese monkeys have become a significant issue in Nepal due to their interactions with human settlements and agricultural areas.

Animal rights activists have also expressed concerns about the escalating conflicts between these monkeys and local farmers, as they often forage in agricultural fields, leading to damage to crops and livelihoods. Finding effective and humane solutions to mitigate these conflicts remains a challenge.

In an effort to address the persistent issue of human-monkey conflict in Nepal, the National Trust for Nature

Conservation (NTNC), in collaboration with the Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation (DNPWC), the Nepal Foresters’ Association (NFA), and the Society for Conservation Biology Nepal (SCBN), organised a roundtable discussion. This gathering aimed at finding solutions to the ongoing menace caused by monkeys and foster collaboration among stakeholders to tackle the issue effectively.

Deputy Director at DNPWC, Ajay Karki, has emphasised the primary objective of the recently introduced relief guidelines, which is to provide assistance even when wildlife causes damage beyond protected areas.

He pointed out that conflicts are escalating due to factors such as water scarcity in the jungle, unregulated waste disposal, changes in the food habits of wildlife, and the rapid learning ability of monkeys. Karki highlighted the need for a comprehensive framework to address these challenges and conduct studies to determine the most effective approach.

During the programme, a four-member panel of experts shared their insights and perspectives on the ongoing human-monkey conflict issue. The panel included Dr. Sabina Koirala, Dr. Krishna Prasad Acharya, a former secretary of Ministry of Forest and Environment, Lekhnath Pokhrel, representing the Rural Municipality Federation; and Dr. Sindhu Prasad Dhungana, Director-General of DNPWC.

The discussions primarily centered around key areas such as policy and institutional roles, the importance of knowledge and evidence-based approaches, practical interventions, and crucial considerations regarding relief provisions for managing human-monkey conflicts in Nepal.

They presented valuable insights into monkey behaviour, environmental conservation, local governance, and governmental perspectives, collectively seeking solutions to the enduring human-monkey conflict.

-original-thumb.jpg)