- Friday, 23 January 2026

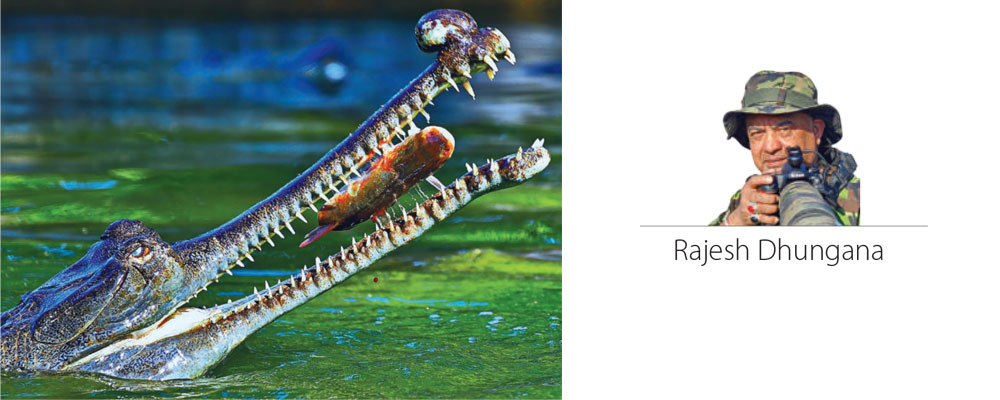

Gharial Conservation Efforts In Nepal

The Bardia district of Nepal stands out as a prominent place of exemplary biodiversity. This region has many rivers, and it offers a rare chance to witness the highly threatened gharials. Belonging to the crocodile family, the gharial (Gavialis gangeticus), also known as the fish-eating crocodile, holds the distinction of being the longest among all living crocodilians in the Gavialidae family. The male gharial is recognisable by its raised nose tip, resembling the shape of a clay pot, referred to as "Ghada." In contrast, female gharials lack this distinctive feature. As male gharials mature, they develop a bulbous nasal protuberance called a "Ghara." While gharials were once widespread in Nepal's major rivers, various factors, including climate change, have led to their confinement to the tributaries of significant water bodies like the Narayani, Rapti, Karnali, Babai, and Mohana rivers. Their former range extended to countries such as Burma, Pakistan, and Bhutan, but unfortunately, they are now extinct in these regions. Today, gharials cling to survival in fragmented populations within the tributaries of the Ganges River, in Nepal and India. The decline in gharial populations has been stark, with their numbers dwindling to a mere 2 per cent of their historical range since the 1930s. Reflecting this alarming trend, the IUCN Red List categorises gharials as "endangered," and the CITES Convention has designated them under Schedule 1.

Features

Male gharials exhibit a length range of approximately 9 feet 10 inches to 19 feet 8 inches, while their female counterparts measure from 8 feet 6 inches to 14 feet 9 inches. These creatures weigh an average of 159 kg to 180 kg. The snout of a gharial has 27 to 29 teeth on its upper jaw and 25 to 26 teeth on its lower jaw. Notably, the callus on the male's snout begins to develop around 3.5 months of age. Its lifespan averages 40 to 60 years. With an olive hue, adult gharials are darker in comparison to their youthful counterparts. They have distinctive dark brown crossbands and speckles. As a gharial ages, its coloration transitions to an entirely black appearance. However, a striking contrast emerges with its belly, which has a vivid blend of yellow and white tones. Structurally, Gharial's head, belly, and hind scutes blend seamlessly, forming a continuous plate. This remarkable composition consists of 21 to 22 transverse series and 4 longitudinal series. While the hind scutes are bony, they exhibit a degree of softness. Gharial's fingers are partially webbed, an adaptation suited to their aquatic lifestyle.

Habitat and breeding

Gharials possess remarkable skill in capturing fresh fish, a talent attributed to their elongated snouts. Beyond this preference for fish, their diet extends to encompass various aquatic organisms, including snails, worms, tadpoles, and frogs, among others. To communicate their sexual maturity, gharials employ a unique tactic: underwater bleating or other distinctive sexual behaviours that generate an echoing sound. During colder weather, their mating activities intensify as they engage with their adult counterparts. As spring emerges, female gharials assemble within burrows, where they lay a clutch of approximately 20 to 95 eggs. A noteworthy aspect of their reproductive behaviour is the vigilant protection provided by the male, who guards the nest with dedication.

Gharials lay their eggs on the sheltered sand banks of riverbeds, selecting a window between the final week of March and the initial week of April. These eggs then undergo an incubation period, hatching in June. Despite Gharial's efforts to shield its eggs from threats, these precious bundles fall victim to predators including foxes, wild boars, predatory birds, otters, and turtles. Female gharials display a remarkable readiness to engage in breeding activities within a mere decade of their birth.

An intriguing facet of their reproductive biology is the size of their eggs, which stand out as the largest among all crocodile species. Each egg has an average weight of 160 grammes and dimensions of 3.3 to 3.5 inches in length and 2.6 to 2.8 inches in width.

Threats

Gharials face various threats that endanger their very survival. These include the demand for their distinctive nasal "Ghada," which leads to their killing. They also suffer from injuries and fatalities caused by becoming entangled in fishing nets. Gharial skins are subjected to rampant hunting and theft. During the rainy season, these creatures build their nests along riverbanks and tributaries. However, their numbers are declining due to factors such as dam construction, sand mining, habitat destruction, illegal egg collection, pollution from human activities, and the impact of climate change. The National Wildlife and Wildlife Protection Act 2029, Sub-section 2 of Section 26, outlines penalties for those who engage in illegal activities harming gharials. As per Sub-section 3 of the same Act, violators could face fines ranging from Rs. 100,000 to Rs. 500,000, imprisonment for up to ten years, or both.

Ganesh Prasad Tiwari, Conservation Officer at Chitwan National Park, reports a decline in gharial numbers at the Gharial Breeding Centre, from 640 to 200 this year. The Centre has successfully released 1,852 Gharials into their natural habitats, with the highest numbers being reintroduced to the Rapti River (1132), Saptakoshi River (115), Karnali River (41), and Kaligandaki River (35). In the current fiscal year, the Rapti River saw the release of 160 gharials. During the fiscal years 2020/021 and 2021/022, gharial eggs were incubated, leading to the birth of 7 and 13 hatchlings, respectively. Additionally, a laboratory incubator yielded 20 gharial hatchlings on June 24, 2023, maintained at a temperature of 32 degrees Celsius. According to Asish Neupane, Conservation Officer of Bardia National Park, the park had housed nine gharials in the year 2015/2016, with their genders not yet identified. Earlier, the centre had nine female and two male gharials.

Efforts to safeguard gharials in Nepal led to the establishment of the Gharial Conservation Project in 1978. This initiative introduced breeding centres, like the ones at Chitwan National Park's Kasara and Bardia National Park, aimed at raising awareness, conducting research, collecting and incubating eggs, and eventually reintroducing gharials into their natural habitats. Since 1978, gharial eggs collected from riverbanks have been nurtured at the Gharial Conservation and Breeding Centre in Kasara. In 1981, the first batch of 50 gharials was released into the Narayani River, followed by subsequent releases into other Nepali rivers. Despite these efforts, survival rates have been disappointingly low, raising concerns about the future of these creatures. Notably, the involvement of local communities has been recommended to enhance gharial conservation in Nepal, particularly after a significant population decline in 2017. The breeding centres have released gharial hatchlings into rivers suitable for their conservation, with a focus on raising public awareness and engaging in scientific research.

(The author is a wildlife photographer. Photos used in this article are by the author himself.)