- Saturday, 27 December 2025

Why can’t Kapalis have houses of their own?

Kathmandu, Feb. 14: Kapalis are an unfortunate clan within the Newa community. They were both sought for their mystical powers and shunned for their perceived ‘uncleanliness’. The rulers of yore brought them inside the core cities to ‘purify’ their kingdoms but, at the same time, prevented from keeping private homes.

Descendants of the Kapalika sect of the Dashnami-Sanyasi Hindu monastic order, Kapalis were as socially marginalised as other so-called ‘untouchable’ castes of the mediaeval Nepal Mandal confederation of Kathmandu Valley and the surrounding areas. But unlike them, they were permitted, in fact, obligated, to reside in strategic locations inside Kathmandu, Lalitpur and Bhaktapur.

According to the book ‘Mesocosm: Hinduism and the Organisation of a Traditional Newar City in Nepal’ by Robert Levy and Kedar Raj Rajopadhyaya, this was perhaps because of the role the Kapalis played to purify the city and its residents by ‘accepting’ the spiritual impurities onto themselves.

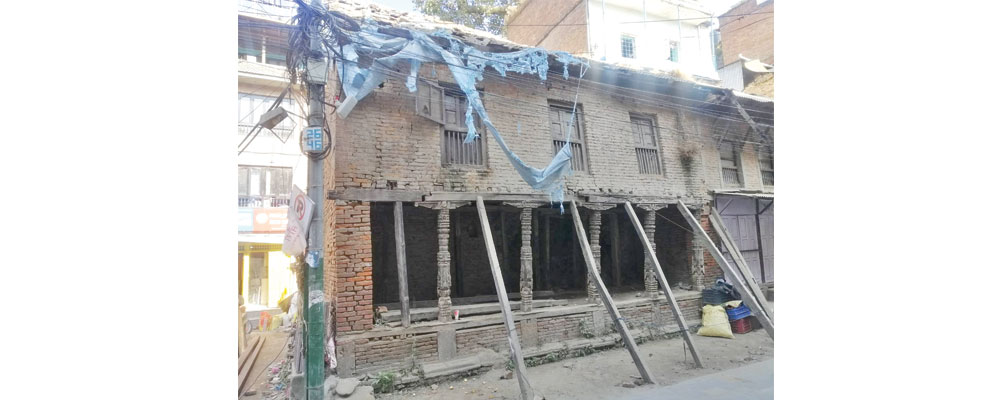

In a Tantric sense, Kapalis were the ritual cleaners of all. That is why they were made to stay in rest houses at major junctions and intersections across the three city-states – a fact that, in the 21st century, is rendering many Kapalis homeless. In Patko, Lalitpur Metropolitan City Ward No. 16, for instance, the family of Gopal Darshandhari has been asked to leave the public shelter Sattal they have lived in their entire lives. Darshandhari is a surname used by members of the Kapali sect.

For at least three generations, he said, the 17th century Sattal has been the only home his family has known. But on December 22, 2022, the ward office sent a letter asking them to vacate the building within three days to enable it to reconstruct the Sattal.

Eleven days before the eviction notice, the ward held a meeting to reconstruct the building, which was damaged beyond repair by the 2015 earthquake. The meeting was attended by Darshandhari’s brother Govinda who requested ward officials to recognise the family as a stakeholder of the Sattal and ensure their right to reside there. The ward did not, so Govinda refused to sign the meeting minutes and consent to their removal.

The ward nevertheless proceeded and issued the three-day instruction. The Darshandhari family moved the Bagmati Province High Court and the matter is currently sub-judice.

“Our family has lived in this house for over a hundred years. But now, the ward wants to dislodge us,” Darshandhari protested.

Without commenting much on the sub-judice case, Nirmal Ratna Shakya, chairman of Ward 16, said that the issue boiled down to ownership. “The Darshandharis may have lived there for long but they do not own it,” he said. “They have to make arrangements because we must rebuild that Sattal. It can collapse any time and poses a great safety risk.”

Darshandhari does not argue that the building, located on two Paisa and one Daam of land near the Patan Durbar Square, needs reconstruction. “In fact, we ourselves went to the ward a few years ago to get permits to rebuild it. But we were denied.”

According to the ward, this denial was, again, because of the ownership question. “A trust by the name of Patko Pati Guthi also claims rights over the property,” Chairman Shakya said.

The aforementioned minutes present the name of Gajendra Shrestha as a member of the Guthi. And he told The Rising Nepal that the Sattal belonged to his family. “The shelter is a property of our Uma Maheshwor Guthi, a private trust run by our family. We perform various rituals at the site four times a year.”

Shrestha informed that he had receipts of Pota (tax) payments his family made for the Sattal. “These are government records that show who the real owners are,” he said.

But Darshandhari claimed that he too held utility bills that support their claim over the house. “The electricity metre installed here by the Nepal Electricity Authority is in my grandfather Ram Nath Kapali’s name.”

Similarly, Shrestha denied that the Darshandharis had been living at the Sattal for generations. He claimed that his father had placed a person there to take care of the house and that person brought the family in in the 1960s.

Meanwhile, Darshandhari presented a statement dated September 7, 1970, in which the then Lalitpur Nagar Panchayat acknowledged his family as the residents of the building and gives it the authority to carry out necessary repairs.

It is to be noted that the government field book remarks the Sattal’s plot, numbered 242, as a place to light ritual lamps. However, above the remark is the struck-through name of Ram Nath Kapali which Rukshana Kapali, Darshandhari’s daughter, said is proof that the Sattal was once listed in her family’s name. “But our name was later cut for some reason,” she said.

Shrestha, too, maintained that he was fighting to preserve his Guthi property and wanted the community members to help put the debate to rest.

This case of the Darshandhari family in Patko is representative of the plight of the entire Kapali community of Kathmandu Valley, Sunil Kapali, president of the Kapali society, said. “The Kapalis have been living in Sattals since the reign of the Lichhavi dynasty. They were the spaces conferred to us by the rulers and societies of the past,” he stated. “But now, we are being asked to vacate the residences we have held for centuries.”

According to linguistic activist Dipak Tuladhar, a Kapali family used to live in the Sattal behind the Sajha Bhandar in Bhotahiti. But now, neither the Sattal nor the family remain. There was also a legal dispute when the Kapalis of Keltole allegedly tried to sell the communal shelter they inhabited.

Kapalis used to live or still do in Sattals near Ason (Kathmandu) and in Kirtipur and Bhaktapur.

Similarly, as mentioned by Dhan Bahadur Kunwar in his doctoral thesis ‘The social and religious life of the Kusle caste group of Kathmandu and the changes experienced’ submitted to the Central Department of Nepalese History, Culture and Archaeology, Tribhuvan University in 2006, Kapalis (Kunwar calls them Kusles which is another name for the Kapali community) also lived near the Maru Sattal Kasthamandap in Basantapur, Kathmandu. But they were forced out in 1966 and the area was placed under national protection for heritage conservation.

Kunwar’s research explores the Kapali/Darshandhari/Kusle caste’s relationship with Sattal buildings and presents a story to explain it. The story, told to Kunwar by one Ram Prasad Darshandhari, says that Kusles are descendants of a man Lord Shiva made from the holy Kus grass. This man was later inducted into the Nath cult by Siddha Jalandhar and given the name Kusalnath.

One day, the Bengali King Gopi Chandra came to Jalandhar to learn the secret to immortality. Jalandhar took him under his wing and made him an ascetic. This caused mayhem in Chandra’s now kingless kingdom. To remedy this, his queens called for a feast at the palace and invited all the Yogis of the region. Jalandhar, Kusalnath and Gopinath, as the king had come to be known, were also invited and when they showed up, they were captured. Gopinath was put back on the throne while Jalandhar was buried alive in a 108-foot hole for distracting the monarch from his duties’. Kusalnath managed to escape and later rescued Jalandhar too.

After his rescue, Jalandhar asked Kusalnath to bring Gopinath back. But the latter refused and advised Kusalnath to create a dummy to pose as him in front of Guru Jalandhar. He complied and presented to his Guru the fake Gopinath.

But Jalandhar realised the deception and angrily cursed Kusalnath, “May you have to live as hermits in the Sattals of Nepal and eat out of leaf plates!” This curse is the reason why the Kapalis spend their lives in homes they do not own.

Another 1988 study ‘Spatial Organisation of a Caste Society’ carried out by Dr. Ulrike Müller-Böker of the University of Zurich also notes that the Kusles live in Sattal houses within city limits near temples that they help maintain.

But the debate is not about Kapalis living in structures deemed to be public in nature. It is about whether, under the present laws and regulations, they are allowed to. And for this, Gopal Darshandhari asked all related bodies and individuals to take the larger context into account.

“A lack of education and awareness prevented our forebears from seeking ownership certificates for the structures they lived in,” he said. “We did not know the bureaucratic requirements. As a result, we were left without deeds and registrations.” Sunil Kapali though pledged support and asked Kapalis to approach the Society with their problems. “We will hold legal consultations and provide any required assistance.”

-original-thumb.jpg)