- Sunday, 22 February 2026

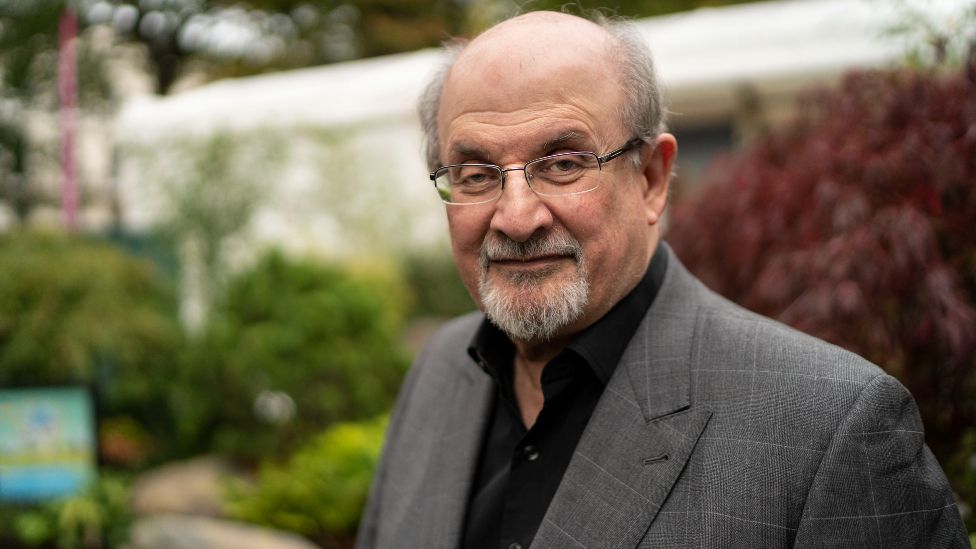

Salman Rushdie: The writer who emerged from hiding

Aug. 13: Over a literary career spanning five decades, Salman Rushdie has been no stranger to death threats arising due to the nature of his work.

The novelist is one of the most celebrated and successful British authors of all time, with his second novel, Midnight's Children, winning the illustrious Booker Prize in 1981.

But it was his fourth novel, The Satanic Verses, published in 1988, which became his most controversial work - bringing about international turmoil unprecedented in its scale.

In the Islamic world, many Muslims reacted with fury to the book's publication, arguing that the portrayal of the Prophet Muhammad was a grave insult to their faith.

Death threats were made against Rushdie, 75, who was forced to go into hiding, and the British government placed him under police protection.

Iran quickly broke off relations with the UK in protest and the country's supreme leader, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, issued a fatwa - or decree - calling for the novelist's assassination in 1989 - the year after the book's publication.

But in the West, authors and intellectuals denounced the threat to freedom of expression posed by the violent reaction to the book.

GETTY IMAGES, The Satanic Verses, published in 1988, brought about an international turmoil unprecedented in its scale

Salman Rushdie was born in Bombay - now known as Mumbai - two months before Indian independence from Britain.

Aged 14, he was sent to England and to school in the town of Rugby, later gaining an honours degree in history at the prestigious Kings College in Cambridge.

He became a British citizen and allowed his Muslim faith to lapse. He worked briefly as an actor and then as an advertising copywriter while writing novels.

His first published book, Grimus, did not achieve huge success, but some critics saw him as an author with significant potential.

Rushdie took five years to write his second book, Midnight's Children, which won the 1981 Booker Prize. It was widely acclaimed and sold half a million copies.

Where Midnight's Children had been about India, Rushdie's third novel Shame - released in 1983 - was about a scarcely disguised Pakistan. Four years later, he wrote The Jaguar Smile, an account of a journey in Nicaragua.

In September 1988, the work that would endanger his life, The Satanic Verses, was published. The surrealist, post-modern novel sparked outrage among some Muslims, who considered its content to be blasphemous.

India was the first country to ban it. Pakistan followed suit, as did various other Muslim countries and South Africa.

The novel was praised in many quarters and won the Whitbread Prize for novels. But the backlash to the book grew, and two months later, street protests gathered momentum.

GETTY IMAGES, Demonstrators were seen protesting against The Satanic Verses in Paris in February 1989

Some Muslims considered it an insult to Islam. They objected - among other things - to two prostitutes in the book being given names of wives of the Prophet Muhammad.

The book's title referred to two verses removed by the Prophet Muhammad from the Quran because he believed they were inspired by the devil.

In January 1989, Muslims in Bradford in the UK ritually burnt a copy of the book, and newsagents WHSmith stopped displaying it there. Rushdie rejected charges of blasphemy.

In Mumbai, Rushdie's hometown, 12 people were killed during intense Muslim rioting, the British embassy in Tehran was stoned, and a $3m (£2.5m) bounty was put on the author's head.

Meanwhile, in the UK, some Muslim leaders urged moderation, and others supported the ayatollah. The US, France and other Western countries condemned the death threat.

Rushdie - by now in hiding with his wife under police guard - expressed his profound regret for the distress he had caused Muslims, but the ayatollah renewed his call for the author's death.

The London offices of Viking Penguin, the publishers, were picketed, and death threats were received at the New York office.

But the book became a best-seller on both sides of the Atlantic. Protests against the extreme Muslim reaction were backed by the EU countries, all of which temporarily recalled their ambassadors from Tehran.

GETTY IMAGES, An Indian Muslin wearing a mask of Rushdie was one of many protesting the author's presence in Bombay in January 2004

But the author was not the only person to be threatened over the book's content.

The Japanese translator of The Satanic Verses was found slain at a university northeast of Tokyo in July 1991.

Police said the translator, Hitoshi Igarashi, who worked as an assistant professor of comparative culture, was stabbed several times and left in the hallway outside his office at Tsukuba University. His killer has never been found.

Earlier that same month, the Italian translator, Ettore Capriolo, was stabbed in his apartment in Milan, though he survived the attack.

And the book's Norwegian translator, William Nygaard, was shot in 1993 outside his home in Oslo - he also survived.

GETTY IMAGES, Rushdie had to go into hiding and received police protection due to the backlash to The Satanic Verses

A prolific writer, Rushdie's later books include a novel for children, Haroun and the Sea of Stories (1990), a book of essays, Imaginary Homelands (1991), and the novels East, West (1994), The Moor's Last Sigh (1995), The Ground Beneath Her Feet (1999), and Fury (2001).

He was involved in the stage adaptation of Midnight's Children which premiered in London in 2003.

In the last two decades he has published Shalimar the Clown, The Enchantress of Florence, Two Years Eight Months and Twenty-Eight Nights, The Golden House and Quichotte.

Rushdie has been married four times and has two children. He now lives in the US and was knighted in 2007 by the Queen for his services to literature.

In 2012, he published a memoir of his life in the wake of the controversy over The Satanic Verses.

The death sentence against Rushdie stopped being formally backed by Iran's government in 1998 and in recent years the author has enjoyed a new level of freedom.

But threats to his life always lingered under the surface, and Iran's current supreme leader - Ayatollah Ali Khamenei - once said the fatwa against Rushdie was "fired like a bullet that won't rest until it hits its target".

-square-thumb.jpg)

-square-thumb.jpg)