- Sunday, 15 February 2026

Media As An Agent Of Change

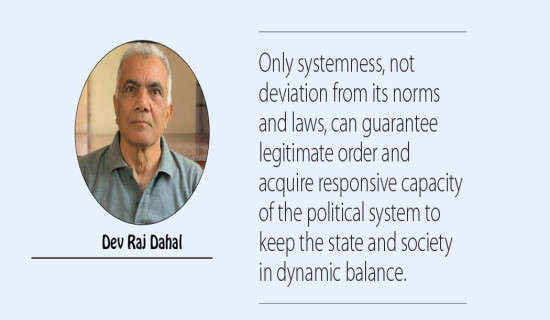

Dev Raj Dahal

The self-image of journalists as a guardian of public interest inspires them to educate the public about human values, inform them about vital issues and help reform society in a rational direction. As a cultural industry, they represent essential virtues -- intellectual values, information and knowledge -- so important to uplift social standards, responsibilise various political and economic leaders for their actions and make people visible in the domain of policy making. Democratic media environment opens the prospect of complex social change, allows the circle of change agents to navigate uncertainty and reform the vices of Nepali society such as blind faith, irrationalism and fatalism.

Democracy as a philosophy of choices also detests the doctrine of social and economic determinism. Media as champions of democracy, human rights, ecological, social and gender justice and peace enable people to acquire cognitive and emotional agility to learn and adapt to change. Many Nepali journalists working as frontline reporters worry about their own vocation, weak condition of law and shaky political milieu hamstrung by polarisation even on public and national interests. They impede the creation of a healthy environment for democratic functions of media serving as drivers of change.

Spurt of social media

The great spurt of online media and social networking sites such as Facebook, Twitter and Instagram balances the usual media culture and offers each knowledgeable individual universal freedom to share their opinion. They look non-pyramidal, cost-effective, instant and powerful means to exercise freedom and blow up public conversation about the scope and direction of social change as per universal spirit. They spark alternative discourses to local, national and global audiences but many of them are less accountable to what they articulate.

New information technology thus cannot be the only proxy to human values upon which the media's ethics resonates. The digital world far from becoming the sole democratic site is vulnerable to rival undercover agents’ plan to control vital information and knowledge. Certain digital spheres are commercialising the Nepali society, deflating democratic spirit and enticing the public to only cheap entertainment.

Despite the information age of today, the bulk of Nepali people is, therefore, ill-informed. They are driven by necessity, poverty, illiteracy, false consciousness and partisan manipulation of news, views and opinions. As a result, creation of an open-access participatory democratic order from the bottom up affirming the sovereignty of Nepali people remains tormenting. The right to know and transparent governance embraced by Nepali constitution collide with the requirement of its essential preconditions.

Skewed diffusion of freedom relative to unequal human development indicators reflects not even distribution of society’s natural amenities. Distributional questions stoke a clash of solidarities with the Nepali polity, if not the state. It constantly sets tension between the nation’s early heritage of tolerance of diversity and current centrifugal pull of clannish style of national politics and spreading the tentacles of geopolitics. Nepal is thus drafted in the high mobilisation of grievances of people and erosion of inter-institutional authority to fulfil them. These gaps keep generating high octane memory to Nepali public recollected often by Nepali media.

In Nepal, power of the majority party in parliament, not normative public reason, governs decision-making at the system level leaving the sub-system either on the edge of estrangement, keep discreet silence or ventilate its disquiet to the public sphere. Nepali vernacular media, many of them linked to the grassroots, are powerful instruments for communication, education and public opinion formation. They vent ideas on how to keep ecological, social, gender and generational responsibility and imbibe democratic values to foster an informed and active citizenry.

The mainstream media beef up the public's struggle for the expansion of civic space and offer insights on how to mitigate pandemic, climate change, poverty, migration, inflation, water scarcity, waste management, economic injustice, corruption, gender violence, human rights abuses and geopolitical tensions. Informed people’s letters to the editors offer solutions to the problematic condition. Infection of society with the virus of scarcity of public good, whatever its causes, generates distorted communication and detaches Nepali democracy from its people. It also marks velvet divorce from freedom from law, accountability and public morality.

Popular sovereignty and liberty of the media are stitched to eternal harmony. But the ongoing jarring flow of information continues to consume this harmony, breeding social distrust and sapping the energy of the media to build civic competence of people to induce desirable social change. Change through updated values and knowledge by Nepali media naturally creates a wider horizon and uncover a new reality. It thus defies the politics of status quo, its impossibility of reforms or resistance people’s aspirations for change evident in each local, provincial and national election.

Media is a high-profile tool to address the sources of problems and improve the framework conditions suitable for the Nepali people to exercise their rights and perform duties. Peaceful change is, however, always bit by bit which adapts to the wisdom of tradition, not catastrophic one which disrupts social order and its resilience to rebound. Journalists’ solidarity can buffer the corporate world’s ability to emasculate media autonomy in the same way as that of prejudiced experts who believe that news coverage should be determined by the interest of owners and advertisers, not by the public interests.

Interest group, cartel and oligopoly of media, like economy, enfeeble democratic spirit of competition and people’s freedom and choice. This capsizes media ethics, curtails editorial freedom and cuts the representation of plurality of Nepali life-world thus accelerating democracy’s fatal corrosion. Journalists’ league with the voiceless of society may add vigour and vitality for social change in its political culture. But it requires their guts to speak truth to power, wealth and authority. In this case, expanding the circle of change agents and sharing responsibility by Nepali media can keep change in the nation in a stable, desirable direction.

Legal enforcement of media laws is another area but democratic media must reinforce the democratisation of institutions and various forms of power and authority not affirming to the rules of conduct. The Nepali journalists’ penchant to mediatise and digitise information and knowledge has, however, cracked many gaps between visual and virtual world, blue and green economy and white colour and blue collar workers indicating democratic deficits in leadership, politics, policy and polity. Connection of a series of mini public spheres can be a remedy to overcome these deficits and craft a unified national communicative space reflective of the nation’s social, cultural, economic and political diversity.

In this context, widening of access to digital skills, monitoring and advocacy and freedom of expression are vital to build bridges across these gaps, reduce social perils, secure communication and ensure safety for journalists through visual solidarity and virtual networking. As a voice of the powerless, journalists must respond to the growing public resentment over the unfulfilled promises of money-friendly leaders that is slowly changing the political landscape of the nation and bringing them back to public political roles.

Time has come to reflect on Nepali media’s works, monitor and measure their certified performance and know whether their efficacy of communication has built an interface between the Nepali polity and its people and vertically dynamise the feedback between the leaders and populace so that information gap between the knower and the general public is expunged for the rational ordering society.

It is equally vital to democratise its digital hub, underline key challenges regarding impunity, self-censorship and safety of journalists and accumulate individual success stories as they have greater emotional appeal and influence than the mass of cases which only reflect an amass of statistics.

Migrant workers’, gender and Dalits’ concerns are receiving greater salience today in Nepali media coverage. The gradual deconstruction of social hierarchy and patriarchy through education, social movements, policy intervention and attitude change is enlarging the inclusiveness of the public sphere. It has effects on building the frame of understanding the world around. Experience and the lessons learned by media persons can enable Nepalis to know how change is possible and how fight against change can be beaten.

Coherence of mission

Pro-active engagement, not dispassionate outlook and objective detachment, with the people’s problems can animate Nepali journalists’ motivation, activism and duty and enable them to become a creative part of Nepali culture rooted into dense conversation which is helpful to effect social change. Measure of success of Nepali media rests on coherence of mission, coordination of technological, resources and organisational means and sustained engagement of its members with the national life-world seeking relationship-oriented transformation.

Change processes set free a flexible social energy hidden underneath Nepali society and its revelation furnish a new social equilibrium through adaptation. Nepali media have, therefore, to keep abreast with the factors that set the prime dynamics and project a better future. Imagining better freedom entails systemic knowledge that helps people to create and sustain a new reality, conquer the problems of dissembled life and muster resources necessary to drive progressive social change for democratic progress.

(Former Reader at the Department of Political Science, TU, Dahal writes on political and social issues.)