- Tuesday, 10 March 2026

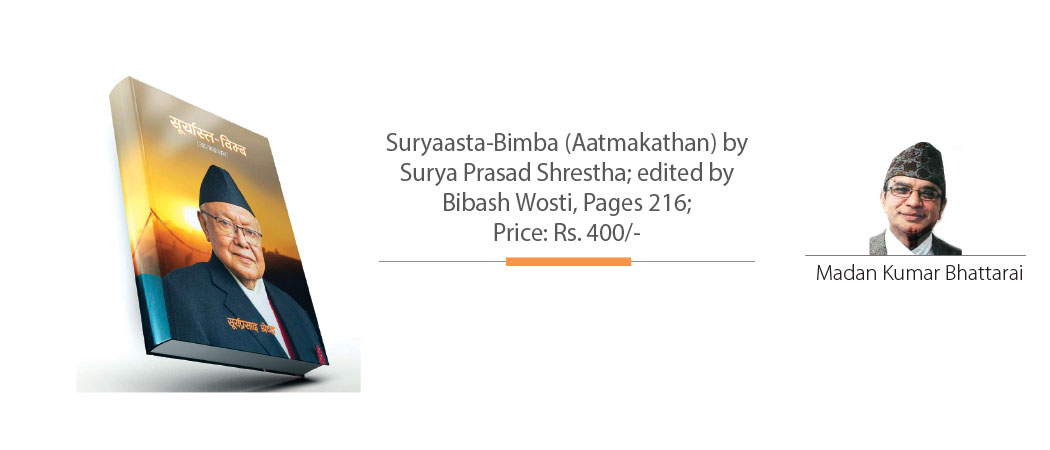

Self-Reflections Of A Public Stalwart

People in public life are found engaged in writing memoirs. Nepal is not an exception to this trend. Public figures depicting achievements, failures and contemporary events, issues and people they encountered in their lifetime, are very significant works. However, there is an unfortunate aspect in the sense that most of such memoirs tend to degenerate into hagiographies rather than real descriptions of things and issues from a dispassionate angle.

Surya Prasad Shrestha has perhaps quite consciously come out with a really commendable act as he is aware of market trends with a plethora of writers indulging in what can be called an exercise in self-eulogy. Shrestha can be called an amalgam of administrative expertise, constitutional position and diplomatic experience if his impressive public profile is taken into account, apart from his variegated social activities and creative endeavours including editing of some magazines.

Surya Prasad Shrestha which literally means best gift of the Sun, has published a book with a self-revealing and defining title, Suryaasta-Bimba (aatmakathan) that can roughly be translated as Reflections of a Setting Sun (Autobiography). Though with a seemingly pessimistic-sounding title, the work is a treasure house of information. Divided into five parts and 43 chapters, the book has an extensive picture gallery.

In his elaborative introduction, the 88-year-old author traces major facets of his life that consist of what he calls a mix of tears and laughter, weal and woe, success and failure, and upheavals that he confronted since childhood days. Calling his endeavour inspired more by necessity than desire, he names some close friends, many of whom became active in public life.

They include Ram Sharan Basnet, Puspa Prakash Pindali, who died in harness in an accident, Dr. Mohammed Mohsin, Kuldip, Kumud, Ram Kumar Shrestha, Bharat Raj Joshi, Gauri Pradhan, Bijay Prasanna Pradhan, Ram Babu Devkota, Rameshwar Pradhan, Kusum Shrestha, Nripendra Kumar Malla, Bhairab Risal and Bhairab Acharya.

Some other friends of his include Bishwa Pradhan, who became a career diplomat, ambassador and foreign secretary, and two political and intellectual figures who made forays into the field of diplomacy, along with other political activities, to assume the position of ambassador, Basudev Prasad Dhungana and Harsha Narayan Dhaubhadel. He also summarises predominant activities of his action-packed life but confesses limitations of the account in the sense that it is not a comprehensive depiction of his life but a selective commentary of various topical aspects that he thought pertinent to highlight.

Originally belonging to the Bhandari or Talchabhadel clan of Bhaktapur, Shrestha's family migrated to Taplejung and pursued a trading business with both China and India, connecting Olangchungola with Kolkata. In terms of study, he travelled to Dharan (twice), Varanasi and Kathmandu, in addition to attending a school at his place of birth.

Shrestha assumed important positions as Secretary in the Ministries of Home, and Industry and Commerce. These posts are taken as some of the plum posts in the government service. Secretaries are generally distinguished on the basis of whether they were selectively picked up, transferred to lesser positions or outrightly dumped, as another senior administrator, Khem Raj Nepal, tends to define them in accordance with prevailing public perceptions.

The author assumed two responsibilities that may be called unique and may not apply to many civil servants. The first is his 15-month tenure in Nepal's first elected parliament as he was a direct witness to the situation prevailing on December 15, 1960, when King Mahendra took a precipitate action against the elected government. The second position was associate member of the National Planning Commission, possibly one-time experiment involving four civil servants.

In terms of constitutional positions he enjoyed, he had two full-fledged positions, first as zonal commissioner or Anchaladhish of Bagmati zone, taken as a lead position among zonal commissioners with the posts abolished after 1990. The second and most important post was Chief Election Commissioner, as this was his second stint in the Election Commission, as he had served there earlier in a junior capacity.

Shrestha's tenure as Ambassador to the United Kingdom may also be termed as a demi-constitutional exercise, as the post of ambassador in our context is highly aspired and greatly propagated but somehow dumped as a halfway house in terms of constitutional sanctity, especially in recent times. The post, though not constitutional, is curiously included in the list of public posts that need parliamentary vetting for all constitutional positions.

Shrestha had a plethora of tragedies that afflicted his psyche both in the family and outside. These include the double tragedy of the death of his father, Laxmi Prasad Shestha, and the sudden disappearance of his mother, Ganesh Kumari Shrestha, when he was just a student of Grade V, thus robbing him of parental affection, love and patronage during his childhood with profound impact on his life. He includes the sad episode of royal massacre at Narayanhity Palace in 2001 as one that greatly shattered him, and enjoys the best impressions of King Birendra.

He also lost his best half, Ginnibaba Shrestha, on February 15, 2018, rendering him lonely as a consequence. Other developments that had a great toll of human lives that inflicted deep wounds in his mind include several thousand people killed both during the Maoist insurgency and the mega earthquake of 2015.

While the book is quite an important contribution, there are minor mistakes that seem to have inadvertently crept in. Mahananda Sapkota, a renowned litterateur, had helped establish Saraswati Middle School, along with Narendra Nath Bastola (and not Narendra Kumar Bastola as has been written in page 11).

Likewise, Sardar Bishnu Mani Acharya, secretary and only chief zonal commissioner in Nepal's administrative history, was not a Dikshit as shown on page 91. Similarly, Rishikesh Shaha, who served the country as ambassador, foreign minister, human rights champion and prolific writer, was not a doctor (page 50). There is also a discrepancy relating to the date of execution of Yagya Bahdur Thapa and Bhim Narayan Shrestha, as they faced capital punishment in early 1979 rather than late 1978.

Despite such insignificant weaknesses, the book is highly readable and I congratulate the author on his creative endeavour. His example should be emulated by many others who can shed important light on their lives along with their readings of contemporary history.

(Dr. Bhattarai is a former Foreign Secretary, ambassador and author.)