- Saturday, 2 August 2025

Questions raised about technology to fight global warming

Wellington, July 4: The startup Gigablue announced with fanfare this year that it reached a historic milestone: selling 200,000 carbon credits to fund what it describes as a groundbreaking technology in the fight against climate change.

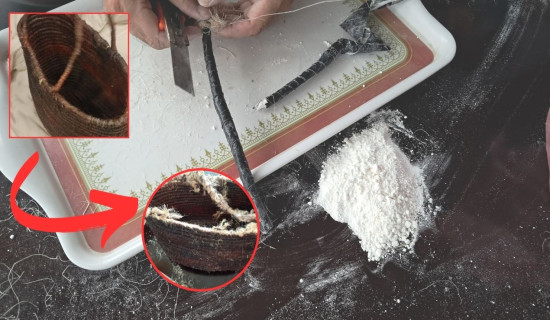

Formed three years ago by a group of entrepreneurs in Israel, the company says it has designed particles that when released in the ocean will trap carbon at the bottom of the sea. By "harnessing the power of nature," Gigablue says, its work will do nothing less than save the planet.

But outside scientists frustrated by the lack of information released by the company say serious questions remain about whether Gigablue's technology works as the company describes. Their questions showcase tensions in an industry built on little regulation and big promises — and a tantalizing chance to profit.

Jimmy Pallas, an event organizer based in Italy, struck a deal with Gigablue last year. He said he trusts the company does what it has promised him — ensuring the transportation, meals, and electricity of a recent 1,000-person event will be offset by particles in the ocean.

Gigablue's 200,000 credits are pledged to SkiesFifty, a newly formed company investing in greener practices for the aviation industry. It's the largest sale to date for a climate startup operating in the ocean, according to the tracking site CDR.fyi, making up more than half of all ocean-based carbon credits sold last year.

The startup is the brainchild of four entrepreneurs hailing from the tech industry. According to their LinkedIn profiles, Gigablue's CEO previously worked for an online grocery startup, while its COO was vice president of SeeTree, a company that raised $60 million to provide farmers with information on their trees.

Shaashua, who often serves as the face of Gigablue, said he specializes in using artificial intelligence to pursue positive outcomes in the world. He co-founded a data mining company that tracked exposure risks during the COVID-19 pandemic, and led an auto startup that brokered data on car mileage and traffic patterns. The company said it had commissioned an environmental institute to verify that the particles are safe for thousands of organisms, including mussels and oysters. Any materials in future particles, Gigablue said, will be approved by local authorities.

Shaashua has said the particles are so benign that they have zero impact on the ocean. "We are not changing the water chemistry or the water biology," Shaashua said. Ken Buesseler, a senior scientist with the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution who has spent decades studying the biological carbon cycle of the ocean, says that while he's intrigued by Gigablue's proposal, the idea that the particles don't alter the ocean is "almost inconceivable."

"There has to be a relationship between what they're putting in the ocean and the carbon dioxide that's dissolved in seawater for this to, quote, work," Buesseler said.

Buesseler co-leads a nonprofit group of scientists hoping to tap the power of algae in the ocean to capture carbon. The group organizes regular forums on the subject, and Gigablue presented in April.

Several scientists not affiliated with Gigablue interviewed by The Associated Press said they were interested in how a company with so little public information about its technology could secure a deal for 200,000 carbon credits.

The success of the company's method, they said, will depend on how much algae grows on the particles, and the amount that sinks to the deep ocean. So far, Gigablue has not released any studies demonstrating those rates.

It's more likely the particles would attract hungry bacteria, Kiørboe said. The rates at which Gigablue says its particles sink — up to a hundred meters (yards) per hour — might shear off algae from the particles in the quick descent, Boyd said.

It's likely that some particles would also be eaten by fish — limiting the carbon capture, and raising the question of how the particles could impact marine life.

Boyd is eager to see field results showing algae growth, and wants to see proof that Gigablue's particles cause the ocean to absorb more CO2 from the air.

James Kerry, a senior marine and climate scientist for the conservation group OceanCare and senior research fellow at Australia's James Cook University, has closely followed Gigablue's work.

In a statement, Gigablue said that bacteria does consume the particles but the effect is minimal, and its measurements will account for any loss of algae or particles as they sink.

The company noted that a major science institute in New Zealand has given Gigablue its stamp of approval. Gigablue hired the National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research, a government-owned company, to review several drafts of its methodology.

Whether Gigablue's methods are deemed successful, for now, will be determined not by regulators — but by another private company.

Amid the lack of regulation and the potential for climate startups to overstate their impact, registries aim to verify how much carbon was really removed.

The Finnish Puro.earth has verified more than a million carbon credits since its founding seven years ago. But most of those credits originated in land-based climate projects. Only recently has it aimed to set standards for the ocean.

In part, that's because marine carbon credits are some of the newest to be traded. Dozens of ocean startups have entered the industry, with credit sales catapulting from 2,000 in 2021 to more than 340,000, including Gigablue's deal, last year.

But the ocean remains a hostile and expensive place in which to operate a business or monitor research. Some ocean startups have sold credits only to fold before they could complete their work. Running Tide, a Maine-based startup aimed at removing carbon from the atmosphere by sinking wood chips and seaweed, abruptly shuttered last year despite the backing of $50 million from investors, leaving sales of about 7,000 carbon credits unfulfilled.

New Zealand's environmental authority has so far treated Gigablue's work as research — a designation that requires no formal review process or consultations with the public. The agency said in a statement that it could not comment on how it would handle a future commercial application from Gigablue.

Pallas, the Italian businessman, said he ordered 22 carbon credits from Gigablue last year to offset the emissions associated with his event in November. He said Gigablue gave them to him for free — but says he will pay for more in the future. (AP)