- Sunday, 22 February 2026

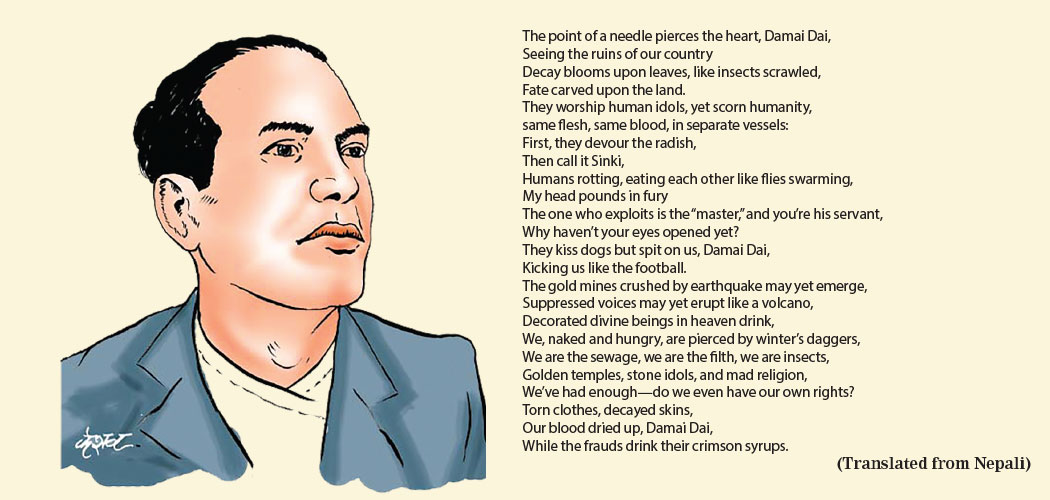

The Sociology Of Damai Dai

We, naked and hungry, are pierced by winter’s daggers,

We are the sewage, we are the filth, we are insects,

Golden temples, stone idols, and mad religion,

We’ve had enough—do we even have our own rights?

Torn clothes, decayed skins,

Our blood dried up, Damai Dai,

While the frauds drink their crimson syrups.

(A piece of the poem Damai Dai by Devkota, translated from Nepali)

Among the many famous poems such as Pagal (The Lunatic), Yaatri (The Pilgrim), and others by the great poet Laxmi Prasad Devkota, one that I find especially moving is a song titled 'Damai Dai'. Invigorated by the heartfelt voice and music by singer Shishir Yogi, the song transcends simple empathy for Dalits who were relegated to the bottom rungs of the caste system. It advocates their rights, expressing intense frustration against the deep-seated injustices in the outdated system. The spontaneity of its expression lends the poem an unpolished, natural quality.

Devkota composed most of his rich works during the time when even uttering the word “equality” was considered a crime. It was an era of the intense and oppressive darkness of the Rana regime, where the Ranas held a license to exploit the resources of the nation.

According to the caste hierarchy, Dalits were cursed to serve the so-called higher castes, a preordained social order with no chance for personal advancement. It was during this era that Devkota wrote passionately about the oppressed Damai community, boldly challenging the ruling class. Writing, 'We’ve had enough; do we even have our own rights?' was a remarkable act of defiance at that time. In the poem, he dares to challenge the wild eyes of the tyrants, writing, 'They devour people, leaving them to rot like flies swarming, a sight that stirs anger in me.' Devkota had already written, 'It’s the heart that makes a person great, not the caste,' a revolutionary sentiment in an age ruled by caste-based hierarchies. Even today, many intellectuals still shy away from openly criticising the ruling elite, either to stay close to power or to avoid losing privileges. But Devkota, a son of Brahmin, dared to uplift the disregarded, oppressed Damai Dai, breaking through the restrictions of tradition with both courage and empathy.

Caste discrimination

The social structure of our country remains burdened by the pride of caste and class. At present, it stands on the verge of restructuring. Initially, class consciousness evolved into a racial superiority complex, which in turn led to caste discrimination. In ancient history, there were two types of people: those who were clever but unwilling to labour and who later on became known as the higher castes, and those skilled in various professions who worked without cunning. The latter became known as Shudras. Some of the Shudras who were punished as untouchable are known as Dalits. Despite the constitutional and legal efforts to abolish these prejudices, the social stigma associated with caste remains alive, and Dalits bear the heaviest burden. They are forced to lead lives marred by shame and humiliation. Since the establishment of the Republic in Nepal, anti-discrimination laws have been enacted, and the principle of inclusivity has inspired the Dalits to join the nation’s mainstream structures. However, many Dalits still walk through life scarred by countless injustices and humiliations.

According to Dalit poet and former MP Bishwa Bhakta Dulal 'Ahuti' in his book Nepal Ma Barna Byabastha Ra Barga Sangharsha (The Caste System and Class Struggle in Nepal), the foundations of the caste system in South Asia were laid about 3,500 years ago. Around 2,000 years ago, under the reign of the Brahmin King Manu, untouchability was introduced into the caste system. The caste system grew more rigid and oppressive over time to ensure the longevity of the so-called higher-caste rule. Later on, this practice entered Nepal with the migration of Hindu rulers from India. There are many communities considered 'untouchable' including Damai, Kami, and Sarki among the Khas-Pahadi, the Chyame, Pode, Kasai, Kusle, and Gaine among the Newars, and the Musahar, Paswan, Badi, Kamaiya, and Chamar among the Madhesi.

Despite being in the modern era, our society is still deeply influenced by Hindu scriptures such as the Mahabharata, Ramayana, and the 18 Puranas. These texts, while valuable from a creative and imaginative standpoint, are often contradictory, mysterious, and even harmful from a social and historical perspective. Many parts of these texts promote compassion, fraternity, and humanity, but their narratives can contradict these very values.

It is unfortunate that we selectively adopt negative lessons from these texts while disregarding the positive. According to some Puranic stories, killing a Shudra is not considered a sin. Ram, the king of Ayodhya, once sought to transcend caste boundaries by eating berries touched by the Shudra devotee Shabari; simultaneously, he killed Shudra Shambuk for practicing penance at the instigation of eight sages, such as Narad and others, upholding the inhuman caste system.

In the Mahabharat, Kirat Prince Ekalavya is denied training in archery by Dronacharya. Later on, he surpasses the royal princes through self-practice. As Guru Dakshina, Drona demands his thumb, ruining his talent. Despite being equally skilled, Sootputra Karna was barred from competing against Arjun and was denied entry to Draupadi’s swayamvar.

In regard to Shudras and women, certain passages in our scriptures encourage dehumanising acts. Yudhisthira forces Draupadi to become a common courtesan to his brothers, and the court of Hastinapur declares that Yudhisthir had the right to gamble her away. This reflects a message that women were little more than property. Ironically, the Mahabharat hails Yudhisthir, Bhishma, and Krishna as ideals. Such narratives, consciously or subconsciously, shape our cultural psyche. Even educated anti-caste and anti-discrimination people sometimes reveal their biased idioms and proverbs unconsciously, which is why caste-based discrimination persists.

Devkota’s defiance

Nearly 2,600 years ago, the Buddha dismissed the idea of a caste-based society. His sangha (monastic community) included respected Dalit monks like Upali, Sunit, and Swati. However, the Sanatan society continued to reinforce casteism, pushing this community, which venerates labour, to the bottom rung of the economic class. Their status was further diminished by being deemed untouchable. Marxism is a dynamic philosophy, but some dogmatic Marxists believe that class liberation alone will resolve the Dalit issue. Of course, abolition of class is essential, but in South Asia, the caste-based oppression inflicted by the caste system cannot be ignored. Why, despite equal economic standing, does our society treat a Brahmin and a Dalit differently? This illustrates that along with the abolition of class discrimination, salvation from the caste system is a must, and caste-based dignity must be restored, too.

In the poem Damai Dai, the Great Poet hammers the backbone of caste and class discrimination, and his expression resonates on a level not of sympathy but empathy.

(Shrestha is a poet, short story writer and freelance journalist.)