- Tuesday, 17 February 2026

Resolution Of Multistakeholder Rows

This writer had participated in a training course on multi-stakeholder conflict mediation led and facilitated by a well-known conflict mediation expert Chris Spies who hailed from South Africa. Chris has been an experienced conflict mediation practitioner and facilitator of capacity building workshops in a wide variety of settings in Africa and beyond. Needless to say, multi-stakeholder disputes, as terms denote, constitute issues that involve two or more parties or groups having substantial stakes and interests in the process and outcome of their resolution.

Such types of disputes can be of different types, scales and substances involving groups, communities, parties, governments, states and so on. The parties involved in multi-stakeholder disputes could be affected directly or indirectly, equally or differently by the occurrence and escalation of disputes. Multi-stakeholder dispute resolution requires employment of what is known as multi-stakeholderism which is a methodology of seeking to ‘bring together actors that have a potential “stake” in an issue and ask them to collaboratively sort out a solution. Key principles and strategies of multi-stakeholder methodology, as emphasised by Chris Spies, include accountability, transparency and democratic mechanisms of engagement, and effectiveness.

Better decisions

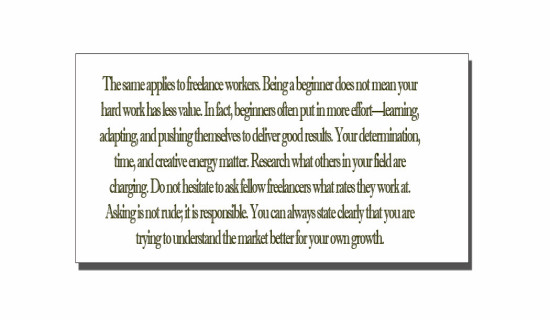

Multistakeholder process provides a tool in arriving at better decisions by means of wider input. The process can help generate recommendations that have broad based support. It can create commitment through participants identifying with the outcome and thus increasing the likelihood of successful implementation. Equity and levelling the playing-field among all relevant stakeholder groups through dialogue and consensus-building based on equally valued contributions from all has been the mainstay of multi-stakeholder process.

The training workshop facilitated by Chris Spies, as mentioned at the outset, was almost a six-month-long course based on reflection in action modus operandi. It refers to active evaluation of thoughts and practices during action. It required us - the trainee participants - to engage in a real multistakeholder dispute resolution process in local communities on the ground. The process allowed the training participants to learn through hands-on engagement in real dispute resolution dynamics. The trainee participants would re-assemble following their field engagement time and again to reflect and share their field observations and experiences with each other.

Reflection in action is thus a form of self-reflective inquiry undertaken by participants in a field situation in order to improve the rationality and practicability of their own practices, their understanding of these practices and the situations in which the practices were accomplished. It is also claimed to be a well-tested methodology of conducting research to usher in transformative change through the simultaneous process of acting and reflecting, which are linked together and nourished through critical reflection. Moreover, it is viewed as thoughtful consideration and retrospective analysis of their performance to construct knowledge from experience.

Chris Spies possessed rich knowledge and experiences in international conflict mediation. He used to remind the trainee participants time and again about the role of a dialogue facilitator to help ensure that the disputing parties could negotiate successfully to arrive at a gain-gain resolution of disputes. The training workshop was organised to respond to emerging needs of the federal political context of Nepal where multistakeholder disputes have been exponentially on the rise and these have manifested in several forms, scales and dimensions.

The decade-long violent conflict between the then government and the Communist Party of Nepal-Maoist (CPN-Maoist) spanning from 1996 to 2006 had exacted a heavy toll on the lives and resources in the country. It had resulted in the deaths of over 17,000 people, including civilians, insurgents, and army and police personnel. It also led to the internal displacement of hundreds of thousands of people, mostly throughout rural Nepal. In the armed conflict numerous heinous crimes, including summary executions, massacres, purges, kidnappings, and mass rapes had been committed.

By signing the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) on 21 November 2006, the government and the CPN (Maoist) had sealed an agreement to end of the hostile armed confrontation and did commit to establish the truth about the conduct of the war with a view to ensure the victims of the conflict receive both justice and reparations. The peace accord also committed to forming two transitional justice mechanisms: a Truth and Reconciliation Commission and a Commission on Disappeared Persons. Though the commissions had been formed twice in the past, these bodies had not been able to execute the mandated tasks due to one or the other reasons. One of the major reasons of the unfinished agenda of the transitional justice has been the lack of consensus on the provisions of the TRC Bill. Only after several round negotiations political parties have reached consensus on the provisions of the TRC Bill that was endorsed by the parliament some time back.

Political impasses

The reconstitution of the commission is yet to be carried out. The government has recently formed a search committee to finalise names of members for the committees. Nepal’s peace process has been more or less a home-grown exercise secured through initiative, participation and transformation of the actors involved in the conflict. The federal democratic constitution authored by elected Constituent Assembly and promulgated in 2015 was an outcome of the CPA. However, less than expected progress on transitional justice realm exposes the weakness of the post conflict peace process in Nepal.

Though the armed conflict between state and the Maoists had ended in 2006, inter-political party and intra-party conflicts have emerged as the major reasons for political impasses in the country. Likewise, inter community, interfaith and intergovernmental, interparty and intraparty conflicts have increased in the political and social canvas of the federal Nepal. There is a need for the massive training initiatives to produce human resources who could assist in resolving multi-stakeholder disputes of different stripes emerging in the federal Nepal.

(The author is presently associated with Policy Research Institute (PRI) as a senior research fellow. rijalmukti@gmail.com)