- Tuesday, 24 February 2026

A Decade Of Heart Health Camp

I want to reflect on an event from a decade ago when I was invited as a guest speaker to the opening ceremony of an 11-day heart camp. At that time, I never imagined it would become one of the largest heart health initiatives undertaken in Nepal. I had the privilege of sharing the stage with distinguished individuals, including Dr. Lin Aung, the WHO representative for Nepal; Dr. Arun Shayami, a renowned cardiologist; Dr. Arjun Karki, a pulmonologist; and the beloved legendary actor Hari Bansha Acharya.

The mega heart camp, held in September 2014, aimed to screen over 5,000 young, seemingly healthy adults from Kathmandu Valley, representing diverse sectors like banking, education, law enforcement, slum communities, media, healthcare, students, housewives, and students. The primary objective was to screen for heart disease and simultaneously gather data for a groundbreaking study on the risk factors for this condition among healthy urban residents. This research was authorised by the Nepal Health Research Council.

The reason I am writing this piece is to reflect on the extraordinary dedication of a young doctor who had just completed his studies at the time. I first met him in 2012 at the Manmohan Cardiothoracic Vascular and Transplant Centre when Dr. Bhagwan Koirala introduced him to me for a personal health concern. Since then, despite my travels across various countries as Nepal's ambassador and for other reasons, I have remained his regular patient, consistently following his invaluable care and advice.

While our relationship as doctor and patient has spanned years, I have made every effort to ensure that this article is based purely on what I personally observed during the heart camp, without any bias or undue praise. The doctor I speak of is Dr. Om Murti Anil, whom many of you know well as one of Nepal's leading advocates for heart health.

Exceeding expectations: 5,500+ benefitted

I remember visiting Dr. Om once when he shared his ambitious plan to screen 5,000 people. I was surprised but didn’t want to discourage him at that point in time. Until then, the Ministry of Health and Population, the Nepal Health Research Council (NHRC), and the WHO had collaborated for a nationwide study—the STEPS survey—which screened around 4,000 people across Nepal. But here he was, aiming to screen 5,000 people without any outside funding or support, determined to do it on his own.

Secondly, the way Dr. Om Murti elaborated the structure and contents of the proposed health camp reminded me of the first Nepal Living Standard Survey (NLSS) 1995/96, which accommodated the health sector under different aspects of households's welfare. The health sector since then has become one of the priority research areas. I knew the result from the research findings may help upcoming researchers to evaluate the impact of government’s health-related policies and programmes on the ground-level living condition of the population and also complement the long-term mission of NLSS.

To everyone's surprise, the 11-day camp exceeded expectations, giving free heart check-ups to over 5,500 people. The camp provided full health assessments, including blood tests for sugar and cholesterol, ECGs, and heart health counseling. While I may not remember every detail after ten years, it's clear this was more than just check-ups. It was also one of the largest heart disease research projects ever done in Nepal, combining medical care with important research in a systematic way.

The participation of the private sector in this commendable initiative was a crucial yet frequently neglected aspect of the narrative. The primary objective of these efforts was to enhance awareness regarding the prevention of heart disease. Although social media was not as impactful at that time as it is today, the campaign still garnered significant attention through national media outlets including, newspapers, radio, television, and online platforms.

Over 200 volunteers dedicated themselves tirelessly during the 11 days of the camp, as well as in the lead-up and follow-up days. In addition to their usual clinical responsibilities of assessing attendees' health, they took on tasks such as data collection, analysis, and presentation with the same level of commitment one would expect at a personal event. The majority of these volunteers were medical students from the Institute of Medicine (IOM). Reflecting on their experience, many can take pride in their contributions to such a noble cause.

Service, research and awareness

Dr. Om's vision for the heart camp extended beyond mere screening. He aimed to leverage the large turnout to gather valuable research data while simultaneously raising awareness about heart disease. At a time when most Nepalis prioritised gastric issues and uric acid over heart disease and other non-communicable diseases, his efforts were crucial. In a single event, he successfully accomplished a three-fold mission: providing healthcare services, contributing to medical research, and educating the public about the importance of heart health.

The heart camp was a testament to the unwavering commitment of Dr. Om, who rallied his family and friends to volunteer and help fund the initiative. I knew that he had taken an extended leave from his hospital duties and had even closed his personal clinic—his main source of income. According to an article I recall in Gorkhapatra, the camp cost over Rs 5 million. The majority of that amount was covered by Dr. Om's personal funds, with the remainder contributed by his close friends. Yet, none of them sought recognition or credit for their donations—unlike today, when small contributions are often followed by self-promotion. This humility was one of the key lessons from the event. It seemed that everyone involved was so immersed in their work that such matters didn’t even cross their minds, exemplifying the Nepali saying, “man, bachan, and karma”—fulfilling one’s promises through heart, word, and action.

Legacy of heart camp

The results of the camp were unveiled on World Heart Day, September 29, with media representatives invited to share the findings nationwide. This data ignited nationwide awareness and paved the way for future health initiatives. I vividly recall the alarming prevalence of risk factors—almost every individual screened had at least one risk factor for heart disease. Prevention is critical—it’s cheaper, more effective, and efficient, yet its value is often overlooked by governments, businesses, and individuals alike.

While working at the Manmohan Cardiothoracic Centre, Dr. Om observed an increase in heart disease among youth. In response to this alarming trend, he authored the book Ma Pani Doctor, which was launched by the President of Nepal on the eve of World Heart Day in 2013.

A year later, he organised a large-scale heart camp that showcased his strategic approach to leveraging significant events for raising awareness about heart health.

Later, I learnt that Dr. Om Murti was honoured with the Best Research Paper Award from the Nepal Health Research Council (NHRC) for this groundbreaking project. The research paper, published in the Journal of NHRC, is titled “Prevalence of Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Apparently Healthy Urban Adult Population of Kathmandu.”.

Glimpses of impact

Reflecting on the past decade, it's clear how visionary this effort was. What was once a relatively unfamiliar topic has now become a pressing public health issue, with a significant impact on poorer communities. Ten years ago, terms like cholesterol, heart attack, and the significance of diet and exercise were not widely understood in Nepal. Today, the foresight of those early efforts is evident, as heart disease has become the leading cause of death in Nepal and a global health threat. Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) now account for over 70 per cent of deaths.

According to the Housing and Population Census 2021, out of 198,463 deaths reported in the year prior, about 98,736 deaths were attributed to NCDs, in Nepal, with, a significant impact on poorer communities due to various factors. Furthermore, the leading NCDs contributing to mortality include cardiovascular diseases, and diabetes. Specifically, cardiovascular diseases account for about 30 per cent of NCD-related deaths, while cancer and chronic respiratory diseases contribute around 9 per cent and 10 per cent, respectively.

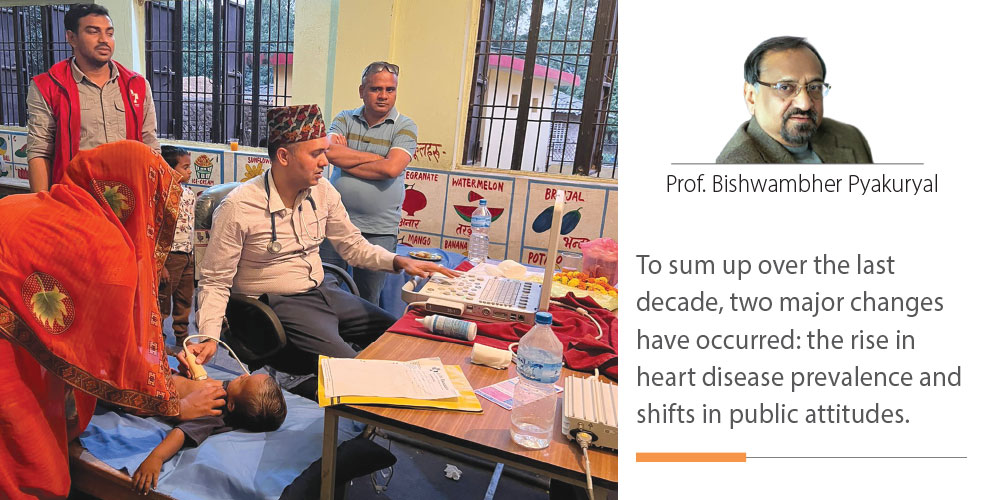

To sum up over the last decade, two major changes have occurred: the rise in heart disease prevalence and shifts in public attitudes. I often wonder if a similar camp today would garner the same level of dedication from volunteers. Back then, with fewer smart phones and less social media activity, there was less emphasis on self-promotion. In contrast, today’s generation often prioritises social media validation over genuine contributions, making it a different landscape for mobilising support.

This heart camp was a monumental achievement, likely one of the largest of its kind globally. Despite their impact, such efforts often go unnoticed. However, a recent Facebook reminder sparked my reflection on this remarkable event. It's a testament to Dr. Om and his team's dedication and vision and a truly deserving contribution to society and the nation.

(The author is a chairman Institute for Strategic and Socio-Economic Research.)

-original-thumb.jpg)