- Tuesday, 10 March 2026

Statute Enhances Inclusive Democracy

The Constitution of Nepal, promulgated in 2015, has become nine-year-old. The historic charter has transformed the country into a federal, secular, and republican state. The country saw two election cycles since the new statute came into force. The three-tier governments are the legitimate yet vital bodies to translate the statute’s provisions into action. The last decade remained crucial to examine the ideals and practical aspects of the constitution. Several legal and administrative structures were created to implement it. Functionality of the federal system, particularly the provinces and local units, came into the spotlight. Their performance, delivery, and economic costs need to be taken into account to weigh the strengths and shortcomings of the constitution, which is the 7th one the nation adopted to address the emerging needs and aspirations of the people.

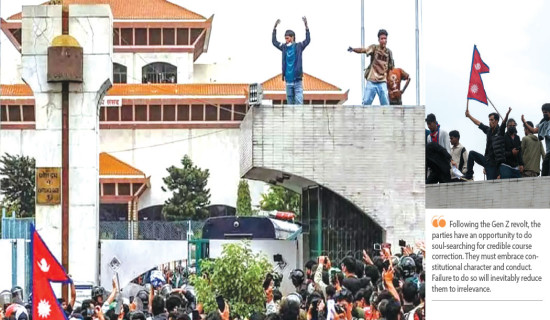

Undoubtedly, the statute has institutionalised epochal changes spurred by the scores of political upheavals and social movements. Building a socialism-oriented economy has remained its cornerstone, seeking distributive justice and bringing the marginalised communities into the mainstream of development. It has envisioned predictable stability, good governance, equity, and inclusive prosperity. However, a growing number of detractors have started to point out the failures of successive governments to live up to the expectations that soared with the introduction of the charter. It has been widely felt that the delivery of public goods and services remained lacklustre and services not up to the mark. At the same time, some critics put blame on the actors instead of the constitution. The onus is on the political parties and their leaders to make the constitution relevant, vibrant, live, and functional.

Experiment

Its nine-year experiment has offered valuable insights for the parties to gauge where the flaws lie and where the reforms are needed. Now the two big political parties—the Nepali Congress and CPN-UML—have formed their coalition government with the objectives of delivering stability, good governance, and prosperity. This is an entirely unanticipated test of statute. The two parties have decided to amend the statute with regard to the proportional representation (PR) electoral system. Similarly, civil society, professionals, and various parties’ leaders have called for revisiting the constitution in order to carry out the reforms in the structures of federal and provincial legislatures and review the rights of local units.

The elected officials of provinces have been alleged to have indulged in facilities and perks while showing apathy towards service delivery, raising the question about the significance of provinces. Many think the provinces have become the platform to manage and adjust the leaders and cadres of the major parties. The cases of corruption, indiscipline, and deviation are rife at the local levels. According to the Commission for the Investigation of Abuse of Authority, it has dragged more than 400 local-level representatives and employees, including the mayors, deputy mayors, and chief administrative officers, for their alleged involvement in corruption.

The constitution has made local units autonomous with 22 exclusive rights. But many local governments have lost their credibility owing to their involvement in the embezzlement of taxpayers’ money. Some local bodies take illegal advantages through the all-party consensus. This sort of immoral act of local leaders has prompted independent observers to press for reviewing the constitutional rights granted to them. A section of the political fraternity has called for the directly elected executive—be it president or prime minister—to maintain stability and equip the parliament with the rights to maintain check and balance of the government’s activities.

Nepal’s constitution has laid greater emphasis on inclusion through elections and various legal instruments. The marginalised gender, castes, ethnicities, and regions have increased their presence in parliament, administration, and local governments due to the PR system and other inclusive provisions. The PR electoral system has been credited with having broadened participatory democracy. This is the brighter side of the main law of land. However, the provision of inclusion has also been discredited to some extent by the elite class that continues to hold sway over the state’s organs. A section of leaders, especially the major parties, have claimed that the PR system was responsible for the government's instability and sought to remove this from the statute, but this line of argument holds no water, for the parties have themselves abused the PR system by giving tickets to their own relatives and cronies. If the spirit of the PR system had truly been embraced, this would have further buttressed the inclusive democracy.

Contradiction

The logic that PR turned the governance dysfunctional can be contradicted on the ground that the governments led by a party that garnered majority vote in the House also collapsed in the past. In a similar manner, the logic that a coalition government, participated in by more than two parties, cannot function efficiently and effectively is also flawed. It is not the matter whether the government is led by a party that holds a majority in the parliament or a coalition government participated in by more than two parties. It is the democratic culture and constitutional behaviour that are the keys to political stability and governance.

Nonetheless, the constitution is not a rigid document; it can be amended when needed. But the agenda of the statute amendment has been raised at a time when it has not gone into full implementation in the absence of necessary laws and regulations. For instance, the laws related to the federal civil services, provincial police, and distribution of natural resources among the three-tier government are yet to be formulated. Our constitution is rights-orientated, which demands corresponding legal apparatus and economic self-sufficiency. The parliament can review the expensive federal design and oodles of structures created in line with statute that do not play any significant role in ensuring economic equality and social equity. If the parties agree to revise the statute, they require forging broader consensus among the parties in the House and other stakeholders outside it. It requires holding extensive deliberation on the would-be amended points. More importantly, it is the due process and reasoned debates that make the statute amendment credible, trustworthy, and acceptable for the people.

(The author is Deputy Executive Editor of this daily.)