- Wednesday, 18 February 2026

Alternate Voices In Cinema

In the context of Nepal, the silver screen has been an ample medium for reflecting the societal landscape over the past five decades. The depiction of society's multifaceted aspects on the silver screen is a challenging task for filmmakers worldwide. While the stratification of social components, in reality, is not as starkly polarised as black and white, with some aspects remaining implicit and nuanced, the dissection of society in films often employs ascribed gender roles. Films often depict the roles of men and women in society overtly, reflecting how gender roles are portrayed in cinema. The world portrayed on the silver screen is seen as a kaleidoscope, representing the diverse ideas and perspectives of the filmmaker. However, while gender stereotypes are prominently featured in movies, their portrayal appears simplistic and rudimentary, lacking nuance and depth on a surface level. That is why a panel discussion on “Reflection of gender stereotypes in the film industry: Changes and impacts over the years” on March 17, 2024, was organised by the Nepal International Film Festival (NIFF) at the Nepal Tourism Board.

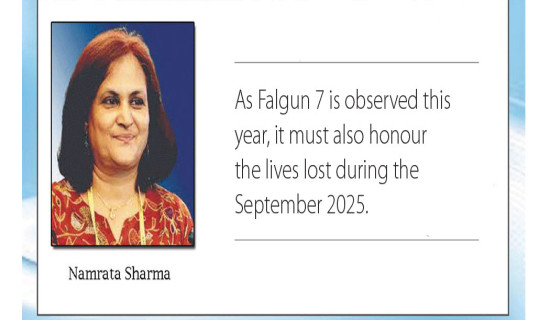

The panellists were Ani Choyin Drolma (singer and social activist) and Shivanee Thapa (Sr. editor and presenter at NTV), Dilrukshi Hundunnetti (director, Centre for Investigative Reporter from Shrilanka), Karin Angele (actor, model, and jury member for NIFF from Germany), and Reema Bishworkarma (actor and model). A two-hour session was moderated by a social activist and journalist, Namrata Sharma. Ani Choying Drolma has appreciated cinema for playing a significant role in her life since it has been teaching many facts, yet she expressed her concern for the portrayal of both women and men. According to her, the culture of showing men as superior to women has persisted throughout cinema. Men are not inherently cruel or unjust. Perhaps this is why people perceive men as superior. “We continue to unconsciously adhere to gender stereotypes,” she said.

Though things are gradually changing, those in authority still need to address these problems. Claiming that a woman like her, who is from a religious community, and Reema Biswokarma are examples of change in society (maybe a little), Drolma indicated filmmakers are the responsible people who should also feel the change. In addition to that, Bishwokarma emphasises that cinema is much more than mere entertainment. It can entertain and educate the viewers as well. She shared that approximately 80 per cent of films are man-centred, with a man as the protagonist, whereas a woman is just a filler. Likewise, being subordinated to male co-workers, she has also experienced many malpractices, such as the tardiness of male co-workers, pay disparity, objectification, and unequal screen space with only a glam doll look (no meaningful presence). She wondered how audiences take it lightly. However, she does not seem optimistic about the change that may happen anytime soon, breaking gender stereotypicality on the screen. The reason for that is the lack of consciousness among filmmakers.

Dilrukshi Hundunnetti has remarked that the 77-year-old Sri Lankan cinema does not rely on the binary composition of man and woman for the projection of real society. The emergence of new female filmmakers, such as Sumithra Peiris, in the 1960s has preserved the voice of women’s voices. Women-centric movies are regarded as trans-formative storytelling even in Sri Lanka. The female filmmakers evolved during that phase. Borrowing the term "sheroes,” as popularised by Indian feminist Kamala Bashin, Dilrukshi suppliantly expresses that not only Sri Lankan female filmmakers but also new male filmmakers are doing justice by presenting women as central characters in cinema.

Another panellist, Karin Angele, accepting the fact of gender stereotypicality on the silver screen, claims the change seen in the portrayal of women is a slow and steady process, even in Germany. Until the 1930s, women were presented as subordinate characters, such as lovers for men, in the cinema. So, she has talked about the age factor that determines the career span for women in cinema. The age of 50 is regarded as the worst age to get films for females since filmmakers choose young actresses. She thanked male scriptwriters for thinking outside the box (from a woman’s perspective), since these days even male scriptwriters are concerned about the role of women in cinema. While discussing the solution for breaking the stereotypical on-screen presentation of women, Shivanee Thapa stresses the need for discourse on the nitty-gritty of cinema among its stakeholders.

Cinema includes a strong narrative that may extend from generation to generation and even cross borders. Hence, keen sensitivity and seriousness should be the prerequisites for everyone involved in the cinema. The three hours and so length of films impact and reinforce the set beliefs and narratives, which create difficult situations for both men and women in our society. The discussion can be summarised with the point that the necessity of breaking gender stereotypicality for men is as essential as for women. In the world of digital reality, women are facing another challenge of getting trolled on social media platforms like women used to get bashed in our real society in the past, which is rampant even in the case of men. So, moderator Namrata Sharma concluded by stating the need for a common understanding of gender roles among filmmakers.

Lastly, the presentation of societal roles assigned to men and women remains a prominent theme in Nepali cinema. Thus, through cinematic language, filmmakers should evolve, including the dynamics of gender roles. Breaking away from gender-stereotypical expectations, they should address issues of patriarchy, gender disparity, and the challenges faced by individuals rather than reflecting prevalent social practices. Likewise, the awareness among the filmmakers is noteworthy since they are creating not only a mirror of the intricacies of society but also offering a thought-provoking space with their films for societal change. Hence, an alternate voice on the silver screen can be a space where audiences can engage to interrogate the complexities of their own lives and the world around them.

(The author is a journalist and lecturer at Kathmandu-based college.)