- Saturday, 5 April 2025

Strategies To Solve Urban Flooding

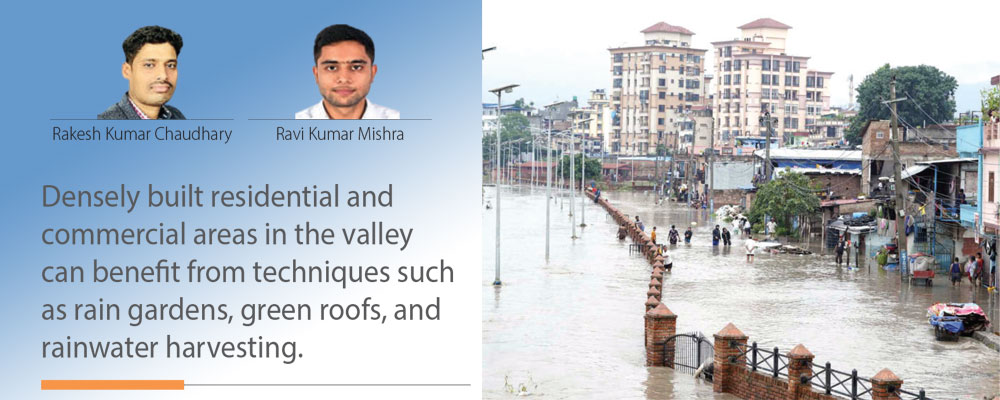

Flash floods in the valley have significantly increased in recent years. Certain areas of Kathmandu city, including Balkhu, Kuleshwar, Narephant, Balaju, Mulpani, and Samakhusi, experience flooding every monsoon. According to national media reports, roads such as Kapan-Tarkari Bazar, Kumaripati, Tinkune, Jamal, Baluwatar, and Bhadrakali experienced flooding. Urban flooding occurs when rainfall runoff exceeds the drainage system's capacity in the area. This issue is emerging in several flat-terrain cities worldwide, attributed to climate change and land-use alteration. However, even for a city situated in the mountains and drained by several rivers, urban flooding may still occur, contrary to initial expectations.

Urban floods can have three possible causes: land cover imperviousness, increased rainfall intensity, and inadequate drainage systems. Traditional landscape development, including man-made elements like buildings, roads, and parking lots, alters the hydrology of the watershed by reducing natural land cover. According to a report by the United States Environmental Protection Agency, only 10 per cent of rainfall becomes surface runoff on 100 per cent natural ground, with the majority being infiltrated or evaporated. However, with 75–100 per cent imperviousness, stormwater runoff can increase dramatically to 55 per cent, with minimal infiltration. Analysis of land use maps of Kathmandu Valley from 1989 to 2016 shows a 412 per cent (Ishtiaq et al. 2017) increase in built-up areas, resulting in a potential increase of over 200 per cent in stormwater runoff. The conversion of natural pervious surfaces to impervious surfaces reduces infiltration and groundwater recharge, thus playing a significant role in flash floods.

The second major factor influencing urban flooding is the intensity of rainfall, which affects the volume of stormwater runoff. Climate change is believed to increase rainfall in some areas, but analysis of 40 years of annual rainfall data (1971–2011) in Kathmandu shows no clear trend of increasing or decreasing rainfall. For example, last year's 24-hour rainfall recorded at Tribhuvan International Airport was 122 mm, the third-highest since 1969 AD. In contrast, the maximum daily rainfall in 2002 was 177 mm, which was significantly higher than last year, but only the floodplain near Balkhu was flooded. Additionally, research conducted by various investigators does not indicate a significant rise in rainfall intensity as a major contributor to flash floods in the valley. Hence, climate change and extreme rainfall have a limited role in flash flooding in the city.

The third factor contributing to flash floods in the Kathmandu Valley is the drainage system, which includes both natural streams and manmade drains. Eight rivers and rivulets, including the prominent Bagmati River, along with its tributaries like Bishnumati, Dhobi Khola, Manohara Khola, Hanumante, and Tukucha Khola, collectively drain the valley. Stormwater runoff from settlements flows along the slope of the terrain and reaches these natural streams. Ideally, settlement areas near river banks, i.e., floodplains, should be planned in a way that minimises interference with natural overland flow. However, unplanned settlements encroaching on floodplains, especially near Tukucha Khola and other similar streams, obstruct lateral inflow, resulting in the inundation of areas such as Putalisadak and its neighbouring localities. This encroachment has become a significant cause of flooding in these areas.

The manmade drainage system in the Kathmandu metropolitan area is a combined-type system designed to handle both sewage and heavy rain. Numerous government organisations constructed and have been responsible for maintaining these drainage systems. However, a significant portion of these systems were designed several decades ago and currently possess insufficient capacity to handle present-day demands. This may be due to inaccurate forecasting of population growth rates and underestimation of runoff coefficients used in the system design. As a result, the discharging capacity of the system is significantly underestimated compared to the current scenarios, leading to inadequate drainage during heavy rainfall events.

Another problem noticed in the valley is that the level of drain outlets is lower than the current high-flood level of the streams. This results in backflow from the drain outlets towards the settlement areas during extreme flood events. Additionally, the high flood levels of the rivers are not constant and are increasing each year due to increased stormwater runoff from the land, as mentioned earlier. Therefore, it is essential to consider future increased flood levels when designing and locating drain outlets in the streams to prevent backflow and mitigate urban flooding risks in the Kathmandu Valley.

Upgrading the existing drainage system can be an effective long-term solution, but it can be time-consuming and costly. In the meantime, implementing sustainable alternatives such as replicating natural drainage patterns and incorporating green infrastructure can be a practical approach to mitigating urban floods in the Kathmandu Valley. Low Impact Development (LID) controls and Sustainable Urban Drainage Systems (SUDS) are examples of green infrastructure approaches that aim to capture and treat stormwater at the source rather than channel it away through traditional piped systems. These approaches promote infiltration and evapotranspiration of stormwater, mimicking natural drainage patterns and reducing runoff. In addition to reducing runoff, LID, and SUDS measures can also help revive and rejuvenate groundwater sources in the valley by allowing stormwater to infiltrate and recharge the groundwater table. This can have multiple benefits, including improving water availability and quality, replenishing depleted aquifers, and supporting sustainable water management practises.

Meanwhile, densely built residential and commercial areas in the valley can benefit from techniques such as rain gardens, green roofs, and rainwater harvesting. These measures can capture rainfall on-site, reducing runoff and alleviating the burden on the drainage system. Similarly, parking lots are often paved and generate large amounts of runoff during rainfall. Pervious pavement, infiltration trenches, and bio-retention areas can be used in parking lots to minimise runoff. Also, detention ponds can be constructed in open squares and parks to manage stormwater in these areas and provide recreational opportunities.

Institutions such as schools and universities can play a key role in implementing sustainable action and educating the public about the importance of rain water management. These institutions can serve as demonstration sites for SUDS and LID controls, showcasing their effectiveness in reducing urban flooding and promoting sustainable water management systems.

In addition to SUDS and LID controls, accurate mapping of floodplains and flood-prone areas is crucial to identifying vulnerable areas and prioritising mitigation measures. These details can inform land use planning approaches, helping to mitigate river floodplain encroachment and minimise flooding hazards. Zoning regulations can be implemented to limit development in flood-prone areas and promote alternative strategies that incorporate green infrastructure.

Effective stormwater management policies and regulations rely on the collaborative efforts of central, provincial, and local governments. National-level policy adjustments offer a structured approach for responsible entities to promote sustainable stormwater management practises. These efforts encompass financial incentives, tax benefits, and other mechanisms to stimulate the adoption of innovative SUDS and LID controls. Additionally, revisions to building codes guarantee that upcoming projects are designed to efficiently handle rainwater runoff, thus diminishing the valley's flood risk.

(Chaudhary is a lecturer at Institute of Engineering, Thapathali Campus and Mishra is a PhD Student, Water Resource Engineering, IIT(ISM) Dhanbad, India.)

-original-thumb.jpg)

-square-thumb.jpg)

-square-thumb.jpg)