The Poor, The Promise And The Constitution

Nanda Lal Tiwari

Before sitting to write some reflection on the sixth anniversary of the Constitution of Nepal 2015, this scribe did want to meet with some porters at New Road of Kathmandu and other places. But, the COVID-19-induced lockdown and other related health safety standards required to be adopted at this time of ceaseless onslaught of the deadly virus created impediments. Finding porters on the street was difficult. They may have returned to their home village or stayed in their rented rooms in the city thinking there was no work to be found as most shops were shut down.

Even then, their image flashed into mind, bringing together some questions. Has there been any change in their life in the last five years? Could the state as the guardian supported them in case they fall seriously sick? Has the state recognized them as someone to be supported? Are their children enjoying constitutionally guaranteed right to education on par with other children? Or they have already developed inferiority complex with regard to the kind of school they go and the education they are getting? A big NO is the answer to all these questions except for the last one for which yes could also be the answer.

This could be an angle, among many others, to see fruits of the new constitution.

Hope For Better Days

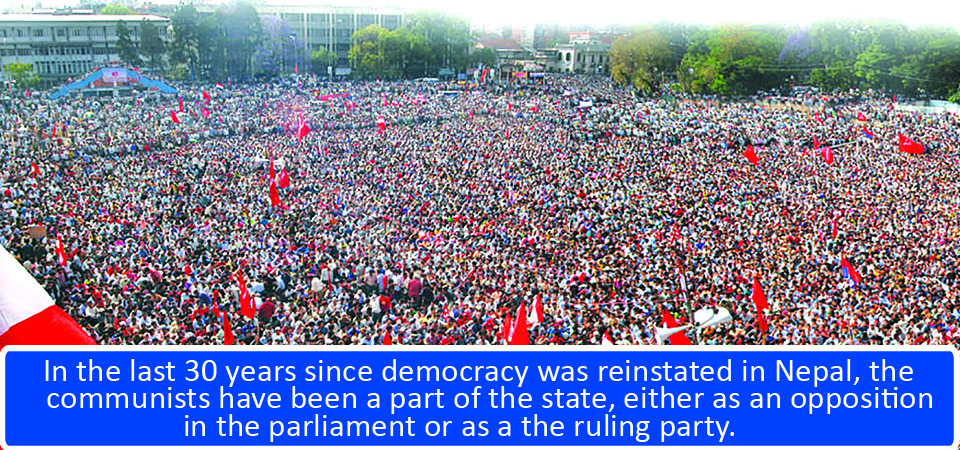

A period of five years is not that long time with regard to implementation of a constitution and its impact. But it is a considerable period to measure to what extent the broad legal framework has injected optimism and made the downtrodden hopeful of better days. No political changes or revolution in the world has ever occurred in the name of the well off. Nepal's people's movement- II in 2006 which was to promulgate a new constitution was no exception. Of course, the constitution has institutionalised the epoch-making political changes, including the federal democratic republican set-up. It aimed at ensuing similar social and economic changes.

One of the most important terms being enshrined in the preamble of the constitution is socialism. This vision of politico-economic is one of the most important features that makes present constitution different from the previous ones. The preamble states that the constitution is endorsed by 'being committed to socialism based on democratic norms and values including the people's competitive multiparty democratic system of governance, civil liberties, fundamental rights, human rights, adult franchise, periodic elections, full freedom of the press, and independent, impartial and competent judiciary and concept of the rule of law and build a prosperous nation.'

Article 50 (3) of the constitution says economic objective of the state is to develop a socialism-oriented independent and prosperous economy. Constitutionally, we are already into the course toward socialism, no matter we may complete the journey in 100 years! And it is a happy matter that all major political parties at the moment in Nepal call themselves socialist including the Nepali Congress. It is understandable that the constitution was passed to fulfill aspirations for sustainable peace, good governance, development and prosperity.

Creating enabling environment for all to enjoy the rights has been enshrined in the constitution. Article 35 (3) of the constitution states that every citizen shall have equal access to health services. Here the question arises as to how to measure equality in access. And it is time to assess what legal and institutional frameworks have been put in place to ensure that this fundamental right is enjoyed by all. Can we go on mushrooming of private health facilities and still claim there is equal access to health services? Article 35 (1) states that every citizen shall have the right to free basic health services from the state. Ironically, just a few weeks ago, the health ministry revealed that as many as 649 local levels have no hospitals of any sort and it made public its intent to establish a five-bed public hospital in all these.

Moreover, just last year, the government came up with‘basic health service package’, which includes 200 services that must be provided by the state-run health facilities to the needy for free of charge. We need to judge this government plan also in the light of Article 47 which is about implementation of fundamental rights and it provisions that 'the State shall, as required, make legal provisions for the implementation of the rights conferred by this Part, within three years of the commencement of this Constitution'. And five years have elapsed since the constitution was promulgated!

One of the toughest challenges with regard to implementing constitution is related to the right to education. Article 31 (2) states that every citizen shall have the right to get compulsory and free education up to the basic level and free education up to the secondary level from the state. Implementation of this Article requires that more public schools are established and all bad circumstances forcing the ordinary people to send their children to private schools will come to an end over the time.

Needless to say, creating enabling environment for people to enjoy the rights guaranteed is far more important than merely guaranteeing them in constitution. Promises that are not translated into action only breed frustration and despair. It is time that analysis is made whether the state is on the right track toward translating the shared dreams into delivery. Implementation of constitution requires political will power and institutional capacity. Both seem to be lacking at the moment. As long as political leadership aligns with the private school education and loathes coming up with plans to gradually replace private schools up to secondary level, the right to free education up to secondary level will remain just a hollow promise.

No Relief Package

The economic crisis, triggered by the COVID-19, has laid bare the bitter fact that not much hopeful situation has so far been made for the poor. It is a pity that there is no data about the poor, working class people. In the lack of data, the state miserably failed to provide any concrete relief to the lowest working class people, including the daily wage worker who lost jobs due to lockdown and were left to survive without any means.

While some business sectors could get some kind of relief package in terms of bank loan interest or delay in payment schedule, the workers in those sectors got absolutely nothing. The relief provided to the poor by the local levels in the beginning went chaotic and there was no relief when real crisis hit the downtrodden. Some social organisations or volunteer groups providing food to the poor at different locations including Ratna Park, the heart of Kathmandu, should be a reminder of how the state has become unable to work as the guardian of the poor in their despairing times. And it is the political parties that operate the state.

(Tiwari is a journalist with The Rising Nepal and writes on politics, economics and international relations.)

Recent News

Do not make expressions casting dout on election: EC

14 Apr, 2022

CM Bhatta says may New Year 2079 BS inspire positive thinking

14 Apr, 2022

Three new cases, 44 recoveries in 24 hours

14 Apr, 2022

689 climbers of 84 teams so far acquire permits for climbing various peaks this spring season

14 Apr, 2022

How the rising cost of living crisis is impacting Nepal

14 Apr, 2022

US military confirms an interstellar meteor collided with Earth

14 Apr, 2022

Valneva Covid vaccine approved for use in UK

14 Apr, 2022

Chair Prachanda highlights need of unity among Maoist, Communist forces

14 Apr, 2022

Ranbir Kapoor and Alia Bhatt: Bollywood toasts star couple on wedding

14 Apr, 2022

President Bhandari confers decorations (Photo Feature)

14 Apr, 2022