Tales About A Bridge

Aashish Mishra

How much do we know about a place that we know? This is certainly a topic we could discuss a lot about. Nevertheless, for the sake of this article, let us say that, if not important, it would at least be interesting to learn about a place we think we are familiar with; because every place has a story. Every street we take every house we see, every stone we step on and every bridge we cross has a tale to tell.

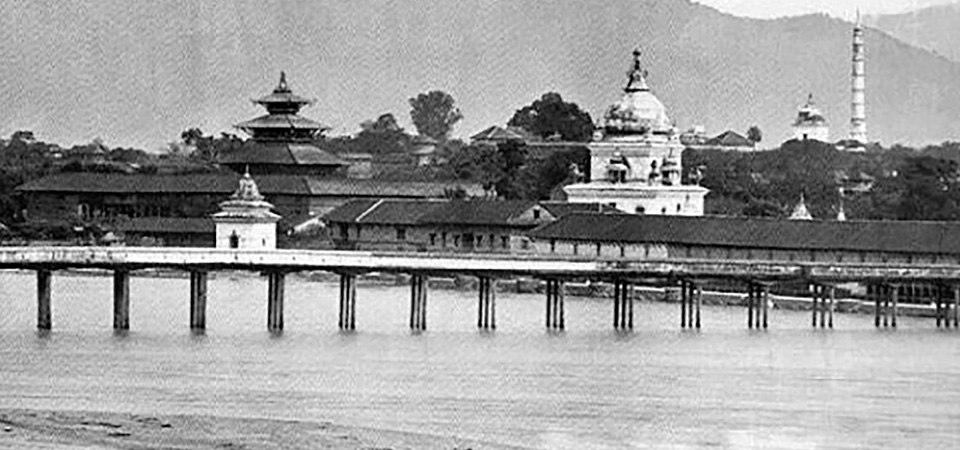

And one of the most talkative bridges, or should I say bridges, are the ones at Thapathali over the Bagmati River. Now at this point, at the risk of over generalising, I would like to over generalise and assume that most of us reading this article in Kathmandu have at least crossed these bridges once. And with that fallaciously sweeping statement, I would like to formally enter the subject of this article by looking at the stone pillar standing between the two bridges. It’s not the most eye-catching object.

Lion Pillar

However, people do notice the golden lion on top of the pillar. When viewed from a passing vehicle, the pillar may look like a solid block but upon a closer look, one will see that it has words carved on it. And these words hold the story that the bridge wishes to tell (I will use the singular because the focus henceforth shall be on the single original bridge built).

As written by late historian and culture expert Madan Mohan Mishra in his paper ‘Lalitpur Bagmati Pulwari Kopundole Hanuman Thanko Shilalekh Nepali Anuvad’ (Nepali translation of the inscription at the Hanuman Temple in Kupondole), the words etched on the lion pillar (for lack of a better name) show that the original Bagmati Bridge had something in common with the Dharahara tower and the Sundhara water fountain in that it was built by Bhimsen Thapa at the request of Queen Lalit Tripura Sundari.

Lalit Tripura Sundari, the youngest wife of King Rana Bahadur Shah, asked her uncle and the then Prime Minister Bhimsen Thapa to build a bridge over what she considered to be the widest part of the Bagmati River near the Kalmochan Ghat to honour her deceased husband’s memory and accumulate merit for his soul. Thapa, who also held King Shah in high regard, complied and the foundation for the bridge was laid on the 11th day of the bright lunar fortnight of the Nepali month of Mangsir in 1867 BS.

Being built on the orders of the Queen for the merit of the deceased King and under the direct supervision of the Prime Minister, the bridge could be compared to a national pride project of today. Construction moved non-stop and no expense was spared. As a result, the bridge only took a year to complete and was inaugurated by Girvan Yuddha Bikram Shah, son and successor to Rana Bahadur Shah, on the seventh day of the dark fortnight of the month of Chaitra in 1868 BS.

To mark the inauguration, Girvan Yuddha performed several oblation ceremonies at both ends of the bridge and also made huge donations to the poor of Kathmandu. It is believed that he was also the first one to cross the bridge.

Mishra, who utilised the translation published by historian Naya Raj Pant for his paper, describes that the original bridge was 1,353 hands (approximately 2,029.5 feet) long and was made of wood.

But the real story begins after the bridge’s completion. And to know this story, we must cross the bridge and come to the Lalitpur side to take a look at the stone inscription standing next to the Hanuman idol.

The inscription details the founding of Kupondole, or rather the nearby settlement of Gusingal. I read the inscription not once but twice but could make very little of it. Reading inscriptions is indeed a great humbling experience for anyone with the interest and the time to attempt to do so. These etched tablets show that you can be able to read something from top to bottom but still not comprehend anything.

But I digress. Coming back to the story at hand, historian Mishra translates this inscription too, some parts of which are written in Nepali and some parts in Nepal Bhasa, in his 2004 book ‘Hamro Bagmati Sanskriti’ (Our Bagmati Culture) and going by that inscription, a story unfolds.

Before the Thapathali Bridge was built, the area was just open fields. After the bridge though, it became the main point connecting Lalitpur and Kathmandu and public movement increased. The erstwhile fields now became real estate open for development. This worried the royal elites. The bridge was a prized construction built in the name of a former king and haphazard development nearby could threaten it.

So, in Magh of 1867 BS, just two months after the foundation for the bridge was laid, the royal palace granted possession of 150 Ropanis of land on the Lalitpur side of Bagmati to one Hanuman Singh Amatya. While his name is mentioned in the inscription, it must be noted that the land was not solely given to him. It was to be under the joint ownership of him and 24 other families, which included the families of his brothers Bhajudhan, Sadashiva and Laxmi Narayan.

These families could only pass the land to their children, buying and selling were prohibited unless with royal permission and all the residing families had to take responsibility for the maintenance of the Bagmati Bridge. If they did not do so, they would be punished, not just by law but by the gods.

The stone tablet proclaims anyone who utilises the land but does not fulfil his or her duty of maintaining the bridge as sinners and places all sorts of curses on them. This shows just how strong a factor religion was in the society of the time that the authorities threatened potential rulebreakers with the wrath of God along with legal penalties.

Anyways, the settlement expanded and by 1870 BS, it had 27 houses along with temples dedicated to Mahadev, Krishna, Ganesh, Bhagwati, Bhimsen, Kaumari, Nateshwor and Saraswoti and several Sattal shelters and Dharmashalas. An idol of Hanuman, the one we still have today, was erected at the settlement’s entrance, which also happened to be the entrance to the city of Lalitpur. In Nepal and especially Kathmandu, Hanuman is worshipped as a guardian deity who protects homes and communities. That is why Hanuman statues can be found at the entrances of all three Durbar Squares of Kathmandu Valley.

Perhaps because of this Hanuman idol or maybe from the name of Hanuman Singh, the settlement near the bridge acquired the name Hanumatpuri. This name somehow turned into Gusingal, just like how the shrine that flanks it on one side became Nhyapa Sya Dya (God who heals pains of the ear) from Nhyapa Swa Dya (God of communication). It is amazing that the change of half a letter turned the demiurge who heard people’s prayers and carried them to the heavens into the patron of hurting ears.

Thank you for coming to my Ted Talk on religious linguistics. Now getting back to the story that is actually over. The establishment of Hanumatpuri was as good as it got. Everything went downhill from there. The settlement continued to expand and slowly turned into a commercial centre. With the rise of the Ranas, the royals lost power and their decree prohibiting the sale of the land lost its teeth. As the economic potential of the area grew, more and more people came in – people who were unaware of the need to maintain the Thapathali bridge in exchange for the privilege of living near it.

Furthermore, the construction of the Thapathali Palace by Jung Bahadur Rana “brought” the bridge under the jurisdiction of the Shree 3 government – a government that had little love for a structure constructed by a family they did not like (the Thapas) in the name of a king they were apathetic to. So, it was a long time coming when Chandra Shumsher demolished the wooden bridge and built an iron one in its place.

But even though Chandra Shumsher tore down the bridge, he did not mess with its spirit. The bridge was still under the care of the Gusingal community, who, while not allowed to carry out any renovation works, was in charge of inspecting and reporting any damages to the authorities.

However, this arrangement changed after the fall of the Rana regime when the central government decided that it was best placed to care for the “public properties.” So great was its love for the structure that, in the 1960s, it decided to completely tear it down and replace it with a concrete quandary built with foreign funds using foreign materials that bore no resemblance to the original in any way shape or form. While building, the government also showed great sensitivity to the ghat underneath that it used the space to pile sand and mud it did not bother to clean afterwards.

Second Bridge

Then came the glorious 90s when democratic governments felt, in all its infinite wisdom, that the people needed a second bridge over the Bagmati in Thapathali and it just had to be built over the Sattal that Hanuman Amatya built at the Thapathali ghat. It also felt that the pillars had to be driven into ghat stones and the lion pillar which stood well out of its path needed to be removed from its foundation and placed in between the two Bagmati bridges where it would be covered by overgrown bushes and be visible for none to see.

And that brings us to today when we have two bridges, neither of which are the original, barely any Bagmati flowing underneath and a ghat that’s become a road on one side and a squatter settlement on the other. What a happy ending!

(Mishra is a TRN journalist)

Recent News

Do not make expressions casting dout on election: EC

14 Apr, 2022

CM Bhatta says may New Year 2079 BS inspire positive thinking

14 Apr, 2022

Three new cases, 44 recoveries in 24 hours

14 Apr, 2022

689 climbers of 84 teams so far acquire permits for climbing various peaks this spring season

14 Apr, 2022

How the rising cost of living crisis is impacting Nepal

14 Apr, 2022

US military confirms an interstellar meteor collided with Earth

14 Apr, 2022

Valneva Covid vaccine approved for use in UK

14 Apr, 2022

Chair Prachanda highlights need of unity among Maoist, Communist forces

14 Apr, 2022

Ranbir Kapoor and Alia Bhatt: Bollywood toasts star couple on wedding

14 Apr, 2022

President Bhandari confers decorations (Photo Feature)

14 Apr, 2022