Ward Committees Have They Become Extractive Bodies?

Mukti Rijal

This writer had evinced interest in the issues of local governance and democratic decentralisation during the early 90s when the nation was caught up with deliberation on how to reshape, revamp and reorganise local governments following the tenets of multiparty democracy established after the popular upsurge of 1990. Since then I have developed a penchant to write and contribute articles, comments and observations on decentralised governance-related issues in journals, magazines and newspapers.

This propensity received a further boost and an impetus during the early years of the previous decade when the nation elected the constituent assembly to write a federal democratic constitution. As a journalist smitten with a bug to produce articles purportedly to refine skills and competence for expression, most of the feature articles that I elected to write during that period had focused to argue and advocate for constitutionally recognised and entrenched local governmental system in the federal set up in the country.

Constituent Units

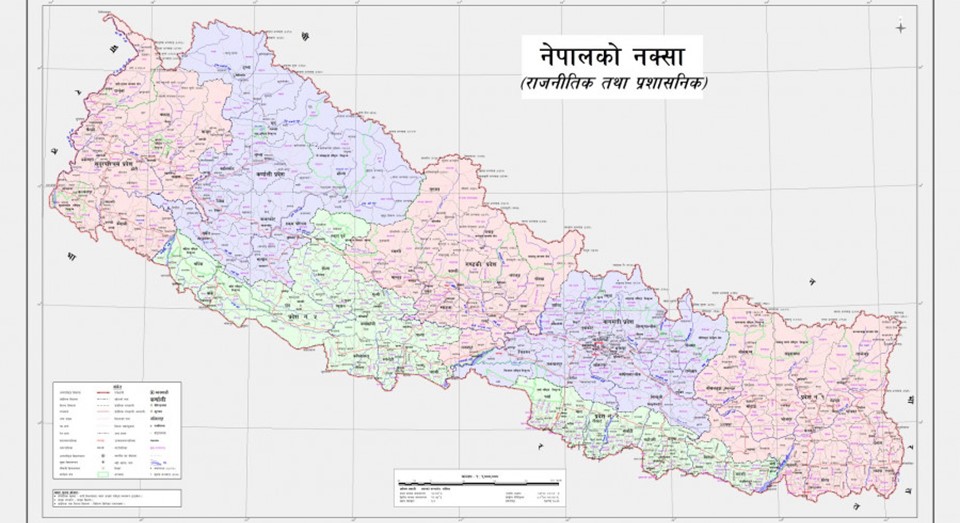

The federal constitution of Nepal promulgated in 2015 has embodied local government as one of the constituent units of the federal state structure. It has entrusted the local government units – Gaupalikas (rural municipalities) and Nagarpalikas (municipalities)- with competence and mandates to exercise state authority more or less at par with the federal and Pradesh (state) government created at the intermediate and central level. The local elections held in 2017 has put democratically elected representatives at the helm of the local government affairs ending more than one and half decades of bureaucratic hegemony at the local level.

Presently, the local government units have become more or less functional across the country, and during the following year, they will be completing five years of their tenure. They will have to go to the polls to renew their mandate. As a protagonist of the democratic local governance, I do get fully buoyed up with enthusiasm when I come across the instances of functionally effective Gaupalikas ( rural municipalities ) and Nagarpalika (municipalities) at the local level. Personally, it gives a sense of justification to me and, of course, this may be the case with many other leaders, constituent assembly members and civil society champions who threw their full weight to advocate for a strong constitutional arrangement for local government institutions through different means and media in the federal arrangement of Nepal. I feel pained with a sense of downbeat when I am confronted with the complaints and accusations directed at the abuse of authority at the local level.

I am tempted to visit the Ward Committee or the Palika offices whenever I find time whether in the Kathmandu Valley or outside in the peripheries to see and observe how the local governments function and respond to the needs of the ordinary populace. It is worth noting the fact that some local governments especially the ward committees have performed exceptionally well despite their limited capabilities and resources to handle a complex range of services to the residents. Ward committee chairpersons do attend the offices almost regularly to ensure that services are delivered effectively to the residents. In case the ward chairperson has to be unable to attend and carry out their functions, they are even found deputing the senior, of course, and the trusted ward committee member for officiating the role.

Neglected

Ward Committees have been instituted in the law as the most important outpost of local governance and public service delivery that the citizens owe to the state in the new federal architecture set up in the country. However, the institutional and organisational capacity of the Ward Committees is poor and has remained more or less neglected despite their enormous roles and responsibilities. These committees operating at the lowest rung have also been crucial in strengthening the revenue base of the local governments. In most of the urbanised municipalities, Ward committees have proved to be instrumental in the collection of resources through taxation and non-taxation recourse.

The important source of income for the municipalities especially in the urban areas like Kathmandu, Chitwan, Biratnagar, Butwal, among others, has been reported to be the homestead tax (Ghar Jagga Kar) also known as the property tax. Schedule eight of the constitution and section 55 of the Local Government Operation Act 2074 have empowered Nagarpalikas (municipalities) and Gaupalikas ( rural municipalities) to levy and collect the integrated property tax in the areas falling under their domain. However, the cutting edge of the Palikas has always been the Ward committees alone that raise revenue using their taxation and non-taxation authority vested in local government.

But, it is alleged that local governments have fixed the rate of the property tax haphazardly to fill their coffer without any rationality. It is even charged that some local governments hike the property tax rate indiscriminately to raise the local revenue base with the faulty assumption of some of the local leaders that they cannot be asked from the authority to account for the books of own-source income. However, this may not be the case for centrally transferred grants because the auditor general's office can examine the books of accounts. However, this is not true both the grants and own source income should be deposited in the local consolidated fund and spent according to the allocations approved by the local parliament(assembly) which are subject to auditing by the auditor general

To ensure that local property tax is levied and raised with the resort of basics of rationality the government has issued the model (namuna)Integrated Property Tax Management Procedure, 2018. The procedure also aims to enable the 753 local levels to exercise the powers conferred on them by the constitution and other existing laws about the collection and management of property tax. This procedure envisages necessary provisions to make the integrated property tax management process clear, transparent and systematic. However, as a model arrangement, the procedure needs to be adapted and passed by the local assemblies exercising the role of the local legislature (Parliament).

Land Tax

It is not very clear how many of the 753 Palikas have adopted it and adhered to its provisions in letter and spirit. The important provision in the procedure has been that the local levels should levy and impose the tax based on classification and valuation of land in their respective areas. A five-member valuation committee consisting of experts shall have to be formed to undertake a value assessment of the land on which tax is imposed. Integrated property tax is levied on the net taxable value of all property (land and buildings combined) of a taxpayer.

According to the procedure, the prevailing market price of the land shall be the main basis of tax assessment. However, the land owned by the federal, Pradesh (state) and local government hospitals, schools and other agencies; religious organizations, bus park, airport, public park, powerhouse, graveyard and stadium; embassies and diplomatic missions should be exempted from property tax. The valuation of the property remains unchanged for a period not exceeding three years.

It is the duty of the Palikas, according to the procedure, to ask the taxpayers to submit details of their immovable property to bring them to the tax net.

Property tax is usually considered to be the major sources of revenue for the local governments in almost all countries in the world. It is said to be a more stable and reliable revenue source than any other tax. That’s because property values are usually less susceptible to short-term economic fluctuations than other major revenue sources. Since property taxes can be secured as they are based on the fixed assets, they are difficult to hide, conceal and evade.

Property taxes help ensure that a broader segment of the population share in the costs needed for the operation of the government. Moreover, property tax systems are more open and visible than other taxes. Tax experts see some disadvantages of the property tax as it falls on the unrealized capital gains, not correlated to cash flow.

This makes a payment more difficult for those who are rich in immovable property but poor in cash income. Property tax appraisals may be perceived as inequitable, especially since assessment ratios differ between property classes. Lack of adequate proper oversight and poor uniformity among comparable properties are prime indicators of inequitable treatment. Appraising property for tax purposes is a resource-intensive process compared to the voluntary reporting mechanisms of income and sales taxes. This makes property taxes appear to be administratively cumbersome and expensive if they have to be made based on a scientific basis and rationality.

Property Tax Evaluation

In our case at the local level citizens do not know who and how their landed property is evaluated and on what basis land tax is determined and imposed. Do the local assembly (parliament) members according to the new arrangement discuss the tax proposals and raise objections on any provisions at the assembly (local parliament) that tend to hurt the interests of residents? Do the Palikas revise the property tax proposals every three years based on the rationality and changing context.

Why are local stakeholders not consulted and deliberations facilitated openly to assure that citizen groups and residents discuss these issues and provide feedback? Do residents receive benefits in return for what they pay as property tax? These are some of the issues that need to be discussed at the local level.

Wider participation of the community people on the issues of local governance and development planning alone can lend rationale and legitimacy to the working of ward committees and enhance local democracy lest they degenerate into irresponsive, irresponsible and unaccountable extractive institutions.

(The author is presently associated with Policy Research Institute (PRI) as a senior research fellow)

Recent News

Do not make expressions casting dout on election: EC

14 Apr, 2022

CM Bhatta says may New Year 2079 BS inspire positive thinking

14 Apr, 2022

Three new cases, 44 recoveries in 24 hours

14 Apr, 2022

689 climbers of 84 teams so far acquire permits for climbing various peaks this spring season

14 Apr, 2022

How the rising cost of living crisis is impacting Nepal

14 Apr, 2022

US military confirms an interstellar meteor collided with Earth

14 Apr, 2022

Valneva Covid vaccine approved for use in UK

14 Apr, 2022

Chair Prachanda highlights need of unity among Maoist, Communist forces

14 Apr, 2022

Ranbir Kapoor and Alia Bhatt: Bollywood toasts star couple on wedding

14 Apr, 2022

President Bhandari confers decorations (Photo Feature)

14 Apr, 2022