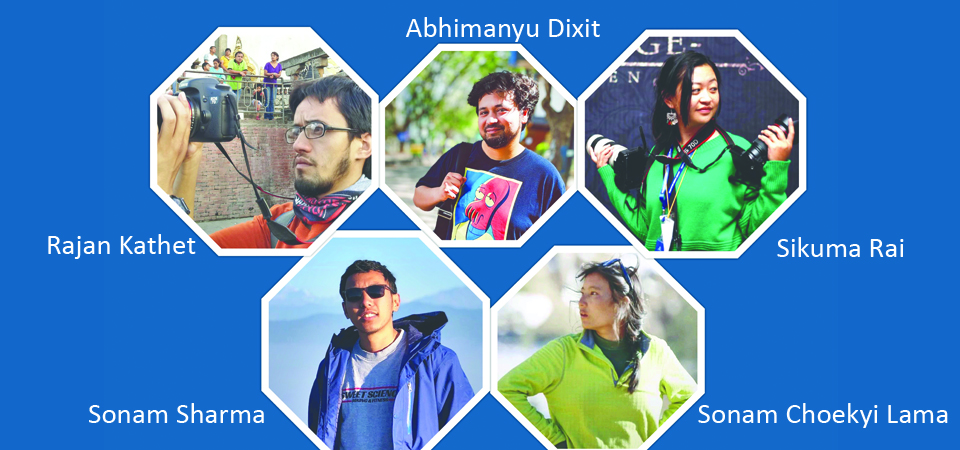

Great stories, short presentations Experiences of five young filmmakers

By Aashish Mishra/Renuka Dhakal

Kathmandu, Feb. 3: Don’t let the name deceive you, short films are no less interesting than feature movies. They have to tell a complete story, develop characters and convey a range of emotions just like a feature film does but unlike features, they don’t have the luxury of 90 minutes or more to do so. Still, short filmmakers around the world have produced masterpieces, reaching at the very heart of the human experience and, in a way, finding the soul of cinema.

In Nepal too, the filmmakers have not only succeeded at presenting great movies in compact packages (with regards to time), but have excelled at it.

The Rising Nepal talked to five such visual storytellers whose subtle efforts in films and documentaries have loud splashes. Some have only just started while others have been at it for quite some time but their common zeal, talent and passion show that Nepali short films have a bright future ahead of them.

Sonam Choekyi Lama

Sonam debuted last year with her documentary ‘The Snow Leopard Calling’ which won the Best Documentary Award Nepal Panorama at the Kathmandu International Mountain Film Festival (KIMFF) 2020. The film, shot in the snow-covered mountains of Dolpo, is less than 10 minutes long but is able to provide a comprehensive insight into the complexities around conservation.

While ‘The Snow Leopard Calling’ may be Sonam’s first film, it is not her first foray into the visual arts. She has been in photography for long and has worked as a multimedia journalist, always focusing on the issues of conservation, environment, women and broader culture of her native Phoksundo and Dolpo.

Sonam is an involved narrator who lives the stories she tells and tells the stories she lives. TSLC is no different. It was an earnest effort to help her sister, Tshiring Lhamu Lama, a conservationist, convey the value of snow leopards to both her community and the wider audience. And because the film comes from a personal space, it is highly relatable with KIMFF stating that “it will resonate with viewers, not only in Nepal but internationally as well.”

Sonam will continue documenting her homeland and telling stories she is interested in but is not sure if those stories will come out in the form of movies. She feels anyone can bring great stories as long as they follow their instincts.

Sikuma Rai

Just like Sonam, Sikuma hit the ground running with her first documentary ‘Come over for a drink Kanchhi’. And just like Sonam, Sikuma is also telling the stories she has lived and experienced up close. The women protagonists of her film are mostly from the same village as her and she has presented their unfiltered emotions, their thoughts, and their life in a beautifully sincere style.

“The lack of representation and coverage of diverse ethnic cultures, the existing stereotypes and dominant narrative of Matwali communities were my main driving force,” Sikuma said. “Also, I was aware about the problems arising due to persisting alcoholism in my village and instead of depicting the straightforward situation I wanted to know the root cause of it.”

Perhaps, it is no surprise then that the film won the Jury Special Mention Award Nepal Panorama at KIMFF 2020.

Sikuma would like to continue making short films and even expand into longer feature films if the story demands it. She feels that the viewers are supportive as well. “Nepali audiences seek originality and want to see the representation of real Nepal. A film that has depth and authenticity is appreciated,” she added. But, at the same time, market realities remain, forcing filmmakers to find alternative ways of making a living. “From my experience, it is difficult to make even a thousand rupees out of short films, except if you win an award.”

Rajan Kathet

Rajan has been working in fiction and documentary films for the last four years. A graduate in Documentary Film Direction at DocNomads, he lived in Europe from 2014 and 2016 and over the years has learnt that making films good and universal is the key to gaining eyeballs. “If your short film is strong, it will definitely attract viewers,” he said.

However, mass market acceptance is something short films have not received yet. While immensely popular among filmmakers, cinephiles and cinema enthusiasts, short movies have not yet become a stable of the people’s cinema diet. The ordinary moviegoers are habituated to watching big stories in feature films and series; shorts do not satisfy them. Hence, studios and digital platforms also do not focus on shorts. “Money matters everywhere,” Rajan added.

This is why short films have mostly been limited to film festivals. “As a filmmaker, you want to go where you are best acknowledged. International film festivals celebrate short films, they provide recognition, contracts and collaboration opportunities to short filmmakers paving the way for them to move into longer movies,” the Berlinale Talent Alumnus of 2017 explained, adding, “Festivals are good platforms to get grants. Some successful shorts win awards – mostly cash and find buyers, which ensure a decent return on investment. Festivals are the ideal platforms to promote and create hype around short films.”

Nevertheless, the lack of market does bite. In Rajan’s experience, a minimum of Rs. 500,000 is required to complete a short film, if the maker is paying everyone involved. But the end product hardly makes a penny in return. “But many do not make short films for commercial success. They are made to be a ladder to climb up in one’s career.”

‘Bare Trees in The Mist’ is his first film to participate in major film festivals and Rajan is currently working on a feature documentary ‘No Winter Holidays.’

Abhimanyu Dixit

Abhimanyu holds many titles-- filmmaker, educator and film campaigner--and has been making movies since 2009. He started out by making films for various international competitions and also won a few. His film ‘By My Troth, I Believe’, made in collaboration with another filmmaker Sahara Sharma was a finalist in the Tony Blair Faith Foundation’s global short film competition.

Outside of competitions, Abhimanyu also writes (penned the movie ‘Intu Mintu Londonma’), directs and produces (produced independent feature ‘Bardiya Sundari’, series ‘Gauthali Ka Katha Haru’ and ‘Maya Bhanne Cheez Estai Ho’) shorts and features for Television, film festivals and YouTube.

Like Rajan, he believes that most filmmakers see shorts as a platform to enter the world of features. “The prospect of bagging lucrative TV and streaming deals with handsome payments when selected in big international festivals also entices people,” he shares.

“In Nepal though, it is a bleak situation for anyone wishing to solely survive off short films. YouTube doesn’t pay that well unless the product is stays really popular for a long time. Film festivals have limited audience, streaming platforms are only just starting and TV channels prefer tele-serials to short films,” he shared his experience.

He feels the need for government intervention to decentralise the production of short films and introduce programmes that not only target the capital but encourage youths from across the country to communicate their stories visually.

Similarly, Abhimanyu wants makers to bring their distinct style and voice to the medium.

Abhimanyu also stands against the belief that cinema is just entertainment. “It is a powerful record of culture, thoughts and ideas and short films can disseminate all that in short span of time.” He laments the fact artistes in Nepal are not acknowledged as cultural agents.

Talking about his motivation for making shorts, he told the TRN that short films were liberating. “They do not follow market trends and are not forced to make their investors [financially] happy.”

“I make short films to experience creation that may not be present in features. My short films are intended to convey my thoughts and feelings of a particular time and space that I have lived in.”

With regards to the advent of digital media, they have provided an avenue, but Abhimanyu notes how shorts have existed since before digital media. “Some of Nepal Television’s first tele-films back in the late 80s and early 90s which were shorts. And before that, shorts existed in the form of cinema reels,” he said.

Sonam Sharma

Ever since his childhood, movies have enticed Sonam Sharma. For him, films are pieces of art that engage special situations, contexts and environments and present them through visuals. This is what ultimately drove him to become a filmmaker himself.

Sonam has been working in visual storytelling, mainly documentaries, for the better part of the last decade and was involved in short films like ‘The Chief Guest’, ‘Random Village Lady’, ‘The Story of Nepal Silk’, ‘Best Himalaya Singing Bowl’, ‘The Last Rites of Takashi Miyahara’ and ‘Mission Everest’.

In contrast to Abhimanyu’s experience of liberation, Sonam feels like shorts are creatively restrictive, bound by time constraints. “But the makers are still expected to deliver a story that is in proportion to feature films,” he said.

Like other short filmmakers, Sonam reiterates how great film festivals can be in helping independent cinema reach out to the audience. “That is why the best strategy is to make a film good enough to be selected in prestigious festivals. That recognition will then help attract viewers,” he suggested.

But, in addition to targeting festivals, short films can also be a media to raise awareness for small communities and market causes.

Sonam believes the rise of streaming has the potential to greatly impact the film space which has enabled filmmakers, regardless of where they are in the world to screen their films on a common platform and viewers to watch them conveniently.

At the same time though, Sonam emphasises that short films do not owe their existence to digital arenas. “Short films existed before such platforms and now too, they can survive without them if the makers think outside the box,” he says.

He also feels that financial limitations discourages many from attempting to make short films and expresses that they can make a leap if the government prioritised them.

For new filmmakers and enthusiasts, he suggested watching and learning from other great works and accordingly, writing, shooting, editing and repeating.

Recent News

Do not make expressions casting dout on election: EC

14 Apr, 2022

CM Bhatta says may New Year 2079 BS inspire positive thinking

14 Apr, 2022

Three new cases, 44 recoveries in 24 hours

14 Apr, 2022

689 climbers of 84 teams so far acquire permits for climbing various peaks this spring season

14 Apr, 2022

How the rising cost of living crisis is impacting Nepal

14 Apr, 2022

US military confirms an interstellar meteor collided with Earth

14 Apr, 2022

Valneva Covid vaccine approved for use in UK

14 Apr, 2022

Chair Prachanda highlights need of unity among Maoist, Communist forces

14 Apr, 2022

Ranbir Kapoor and Alia Bhatt: Bollywood toasts star couple on wedding

14 Apr, 2022

President Bhandari confers decorations (Photo Feature)

14 Apr, 2022