56th Anniversary Special

Check List For A Pioneer Daily

P Kharel

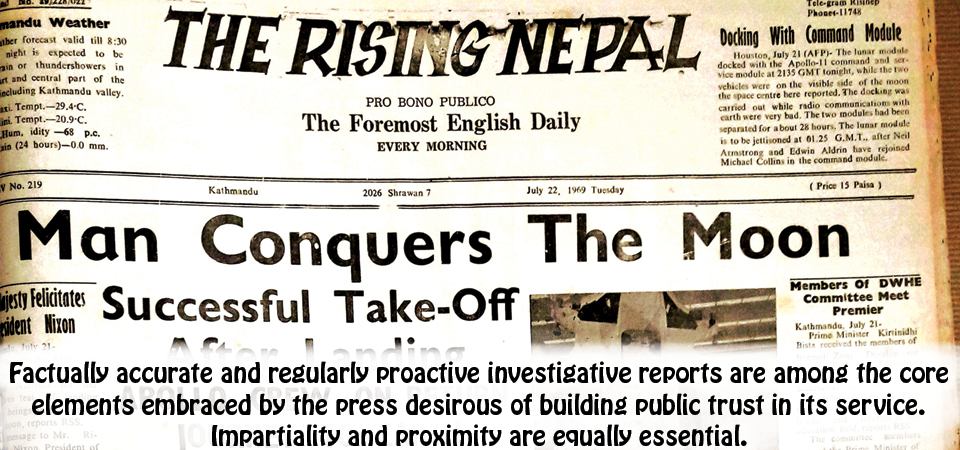

December 15 night, 1965. Only hours away the country’s first broadsheet daily in English, The Rising Nepal, would hit the newsstands, i.e., the Bhugol Park and the Pipal Tree along the New Road and elsewhere. The newsroom was a hive of activity, crammed as it was with the editorial staff and senior administrative staff plus some officials from the government.

With more than a dozen tabloid-sized news dailies in Nepali and English already circulating in the sparse market, when Tribhuvan Highway was the only major road link to the rest of Nepal outside Kathmandu Valley, TRN debuted amid immense elite attention and public anticipation that December 16.

In the previous days, a number of dummy editions with limited copies had been printed and distributed to the palace, prime minister’s office, high ranking officials and noted scholars for perusal and feedback. Members of the editorial section read the entire paper from the mast head to the print line. Barun Shumsher Rana, TRN’s founder editor had the distinction of having also edited the country’s first news publication in English before it closed shop for good after a handful of issues.

Printer’s devil

The printer’s devil was, and still is, a recurring Achilles heel. This issue recalls an anecdote narrated by Indian New Delhi journalists back in 1989 when this scribe served as Gorkhapatra Sansthan’s foreign correspondent. Covering the story of Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru becoming independent India’s first prime minister, the Printer’s Devil danced when a daily paper carried the headline: “Bandit Nehru Crime Minister.”

Going by some of the anecdotes circulated by the founding editorial team, TRN also had its ample share of embarrassment and anxieties, with news headlines and narratives like “Hole of queen significant” and “Crown Prince Birendra was born out of wedlock”.

Translation work, too, can be messy. In one of the news items translated from the work of a Gorkhapatra reporter, I had to turn red faced. Gorkhapatra’s reporter Puru Risal’s story on “Putali pradarshan” was translated as “Butterfly exhibition”. “Putali”, in Nepali, denotes doll as well as butterfly. This novice journalist with only a few months’ experience in journalism preoccupied by recollection of butterfly collection hobby of many school day friends.

Another absent-mindedness produced the embarrassment of having typed Nepal Banijya Bank for Rastriya Nepal Banijya Bank in a business report written by a Gorkhapatra colleague. TRN’s next door neighbour Nepal Bank Ltd might have somehow affected the mind’s working and hence the Translator’s Devil at play.

A Sri Lankan journalist, when on a study tour in the United States in the 1980s, narrated an incident concerning a Sinhali news daily that carried a story translated from English. The report had something like “At least five persons were killed when police sprinkled petrol and fired on a protesting crowd pressing for fulfillment of its demands.” The narrative in the original story, however, read: “At least five persons were killed when a police patrol fired on a protesting crowd...”

Chasing credibility without letup creates the feel for the public platform when audiences begin experiencing it. Credibility is in the public perception. Expediency arising from his perception of partisan press made America’s third President Jefferson to bribe journalists to do his bidding.

While professionalism manifests the cradle of credibility, impartiality represents a virtue that a large number of news organisations find difficult to stand by through thick and thin. Political bias in the American press was widespread in the 19th century. The term media responsibility became a lofty idea that found currency in the post-World War I public debates. The focus began on call for media accountability while the decades since the 1970s acknowledged the value of media transparency. Media action is in accurate and precision reporting that is free from partisan leanings.

Candid opinions are more often confined to private conversations. When penning their views in black and white, the same lot exhibit tremendous reluctance to come anywhere close to airing clear and frank views they harbour.

In any branch of communication, the key players can be seen in different frames—discreet trustees, casual commentators, indifferent observers or predators keen on grinding their personal axes. On the other hand, information outlets are expected to dig and share their findings with audiences. Their collective capital tosses up media credibility contributing to strengthening the media status as a repository of public trust.

So much so that Thomas Jefferson, who drafted the 1776 declaration of American independence, is credited with lauding newspapers in glowing terms: “Were it left to me to decide whether we should have a government without newspapers or newspapers without a government, I should not hesitate a moment to prefer the latter.”

By the time he served as the third president of the US, his views had changed: “The man who reads nothing at all is better educated than the man who reads nothing but newspapers. I do not take a single newspaper, nor read one a month, and I feel myself infinitely the happier for it.”

Essential elements

Factually accurate and regularly proactive investigative reports are among the core elements embraced by the press desirous of building public trust in its service. Impartiality and proximity are equally essential. To quite an extent, Nepali media fail in adhering to the proximity factor that calls for prioritising space to newsworthy events and personalities that their audiences can relate to their interests the most.

Sports and entertainment pages make this amply clear in Nepal, where disproportionately copious space is given to events that are hardly familiar to an overwhelming majority of the audiences. For example, Hollywood activity is accorded considerable space as against the fact that hardly a dozen movies churned out by the Vatican of American productions are exhibited outside Kathmandu and Lalitpur.

It is both a challenge and an opportunity for TRN editors and management brains to ensure these aspects of so significant a sector that prides in being labelled “the Fourth Estate” along with the other branches of the state—the executive, the legislative and the judiciary. No institution consolidates its position simply by basking in the winter sun.

The above narrative should serve as a modest check list for the younger generation of editors at TRN, the country’s second oldest existing daily, in their efforts at not only competing with rival media groups but also adding to its score notched up so far. TRN should respond to the challenge as a commitment or as a compulsion.

(A noted media instructor, Kharel is former editor-in-chief of this daily)

Recent News

Do not make expressions casting dout on election: EC

14 Apr, 2022

CM Bhatta says may New Year 2079 BS inspire positive thinking

14 Apr, 2022

Three new cases, 44 recoveries in 24 hours

14 Apr, 2022

689 climbers of 84 teams so far acquire permits for climbing various peaks this spring season

14 Apr, 2022

How the rising cost of living crisis is impacting Nepal

14 Apr, 2022

US military confirms an interstellar meteor collided with Earth

14 Apr, 2022

Valneva Covid vaccine approved for use in UK

14 Apr, 2022

Chair Prachanda highlights need of unity among Maoist, Communist forces

14 Apr, 2022

Ranbir Kapoor and Alia Bhatt: Bollywood toasts star couple on wedding

14 Apr, 2022

President Bhandari confers decorations (Photo Feature)

14 Apr, 2022